Kristina Dolgilevica reports from the most hospitable corner of the world.

In September Astana, the capital of Kazakhstan, hosted the fifth World Nomad Games – nicknamed “The Traditional Olympics”. This major international ethno-sporting event took place from September 8 to 13, and welcomed over 2,430 athletes from 89 countries who competed in 21 sports and contested 97 sets of medals. Kazakhstan topped the overall medal chart with a total of 112 medals, of which 43 were gold. Their friendly neighbour Kyrgyzstan came in second with 65 medals, of which 19 were gold. The Kyrgyz Republic, the host of the first Games, was handed the baton, (or in this case a torsyk, a traditional leather vessel) for WNG 2026, about which details will be announced shortly. In this article, as well as reporting on the archery events, I would like also to try to give some idea of the range of other sports, and the spectacular atmosphere of the whole event, the scale and magnitude of which has the power to transform the future of traditional sports, and to unite peoples with differing customs, skills and heritage. I hope more traditional archers will be inspired to consider preparing for the next Games, now that traditional archery has moved on far beyond the amateurism of past decades.

When you travel to an event like this, you do not travel there just for archery, you travel there to experience a whole universe, and witness history. The selection of dates – September 8 to 13 – itself has meaning. September is the month the nomadic tribes would customarily stop for winter camp having completed their migration. The winter camp would see the yurts (traditional tents) fixed until the favourable weather returned; and all this was celebrated with various rituals, games and competitions.

‘NOMAD – A MEMBER OF A PEOPLE WHO HAVE NO FIXED RESIDENCE BUT MOVE FROM PLACE TO PLACE USUALLY SEASONALLY AND WITHIN A WELL-DEFINED TERRITORY.’ MERRIAM WEBSTER

DICTIONARY

Programme, Locations, Logistics

The programme consisted of three main parts: sporting events, cultural events, and the scientific conference. Each of the programme blocks held different daily events and many more cultural and immersive experiences were scattered throughout the capital for the general public. The organisers decided that the infrastructure of the event should be “linear” for better transportation and so that it can include all six major metropolitan landmark facilities: the Astana Arena Stadium, the Kazanat Racetrack, the Wrestling Palace named after Zh. Ushkempirov, the Alau Ice Palace, the Qazaqstan Athletic Sports Complex, and the Duman complex. Traditional intellectual games, like the Turkish Mangala, or Togyzkumalak, were held at hotel Duman, where most of the contestants were housed. The scientific conference took place at the spectacular National Museum of the Republic of Kazakhstan; of particular interest and importance was a special session on traditional archery and its fate, but more on that later.

To operate on such a large scale and to assist movement from one location to another, over a hundred free shuttle buses ran – like clockwork – transporting both participants and visitors, with only the occasional delay. One of the key differences between these Games and the previous ones in Turkey, at Iznik, is that all those involved had a chance to see the city and had total freedom to travel and explore, either on foot, or by using the cheap public transport and affordable taxis. However, unlike Turkey, Kazakhstan did not cover the air travel expenses, but it did provide accommodation in comfortable hotels, food and transport, for participants and major media representatives in-land. In Turkey, participants shared metal containers placed by the Iznik Lake, which were far from comfortable; I took part as an archery athlete in WNG 2022. Furthermore, in Kazakhstan, all parties, from athletes to media, were assigned a coordinator; I decided to not use this service, but inquired about the schedule on several occasions, and my requests were promptly satisfied. Some participants did complain, but my feeling is that in most instances it was down to impatience.

Lastly, media and press could make use of two press centres, one in the main television building, Kazmedia, another (much to my satisfaction) overlooking the ground archery field. A special café catered to the media daily, offering hot and cold drinks, local pastries and substantial snacks, as well as local fruit and sweets. It made for a pleasant treat.

A few notes on hospitality and organisation

Out of all the countries I have visited, Kazakhstan wins the hospitality stakes. The Kazakh people are so warm and welcoming to guests in their country; they really want you to enjoy the experience, and to learn about their culture, and they will chat for hours answering any questions you might have. In most parts of the world we are not used to such displays of openness and generosity, but in Astana whenever people saw the WNG lanyard over my neck they came over, in supermarkets, bazaars, or on the streets, and insisted on paying for my food, or giving me food, or simply asking if I needed advice. An acquaintance remarked that their friendliness was triggered as soon as they heard anyone speaking a foreign language – which was also true. Everyone in the vicinity of the event, including the volunteers, of whom there were about 1,600, were trained to handle the large number of visitors with utmost due diligence, and spoke excellent English. My mother-tongue is Russian, and as all Kazakhs speak Russian (many of them do not even speak their own native language, thanks to Soviet education), I spoke to anyone and everyone, everywhere, inside and outside of the event, and confirmed that the Kazakh people are proud of their land, history, and culture and eager to share it. The best way to experience this is to travel there, which I highly recommend.

Do you have to be an heir of the “nomads”?

The “Nomad” in the name implies that only the heirs of the nomadic civilisations are allowed to participate – but it is not so – all countries were welcome. On the other hand, it raises questions about event selection and equal participation. For instance, how can an inexperienced team from, say, Lithuania take part in so many Kazakh national sports, with such little experience? That is bound to shift the medal count pendulum in the favour of the “original nomads”. However, similar observations can be made about the modern Olympic Games, where exposure and expertise favour those who have access to it. As for WNG, it goes to show that we are at a stage where 89 countries can join and compete on equal grounds, win or lose. What matter most is the curiosity about other cultures, as well as the desire to share your culture with others.

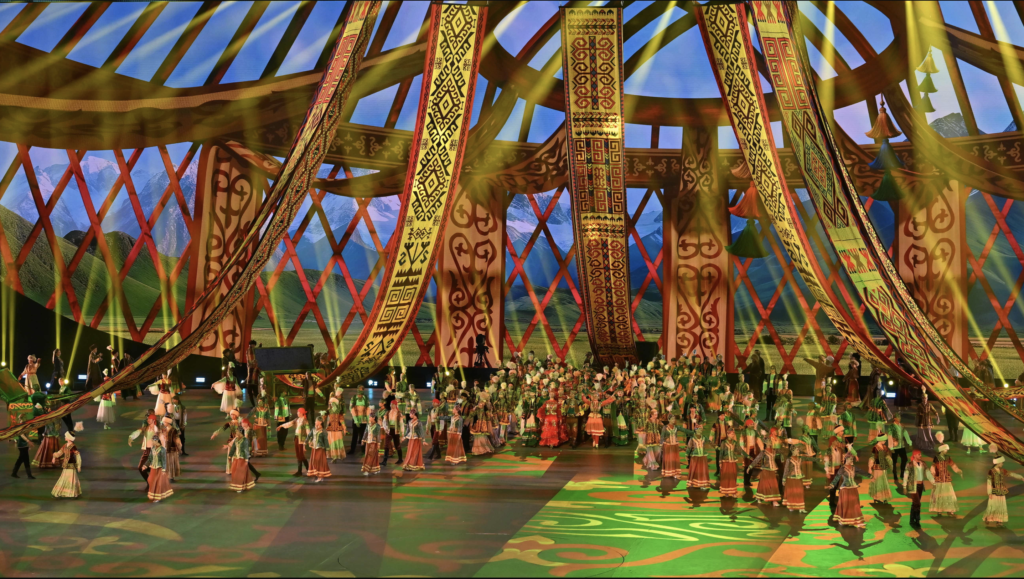

Opening Ceremony

The Opening Ceremony was held at Astana Arena, the country’s largest stadium. Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, the Kazakh president, was present, along with other foreign political dignitaries. In his opening speech Tokayev had this to say:

“These Games promote nomadic civilization at the global level. Sport itself is a symbol of respect and solidarity. Its key purpose is to strengthen friendship among nations. Kazakhstan is known to everyone as a land of peace and coexistence. Indeed, various ethnic and religious groups coexist peacefully here. We have established close ties with both neighbourly and distant countries. We wish to see other states also live in harmony with each other. I am confident that the Nomad Games will help foster international solidarity”.

Reading between the lines, this and other official statements in the media point at the fact that, besides the efforts to preserve the cultural heritage of the ancient peoples, there is a larger agenda; the birth of a bigger international ethno-sport federation. Who will be at the helm?

Sports Programme

Almost two and a half thousand athletes took part in twenty-one different sporting events. The programme was vast and included several traditional wrestling disciplines like qazaq kuresi, where traditional wrestlers, called baluans, employ a variety of grabbing techniques standing up to overpower their opponent, or alysh, the traditional belt wrestling, as well as kurash, similar to judo, and koresh, a Tatar belted martial art dating back to antiquity. There were various sports aimed at demonstrating physical strength and endurance – like the Powerful Nomad, a variation on a strongman competition. This event consisted of multiple feats which were strictly timed, one of which was to load a 115kg beam onto one’s shoulder and to perform as many deep squats as possible, another to drag a horse-cart weighing in at 150kgs across the sand – many did not manage to move it at all! Mas-wrestling, a variation of tug of war native to northern Russia was also represented and both men and women competed in their own categories. In Mas-wrestling, opponents sit opposite each other, resting their feet on a board placed on its edge, and grab a stick with both hands. To win, the athlete must snatch the stick from the opponent’s hands or pull him to his side along with the stick. The match lasts until two victories of one side. Conventional tug-of-war was also represented, where ten men and ten women made up the line-ups by gender. But by far the most spectacular and brutal was the horseback wrestling. Contestants wrestle whilst sat in their saddles, with the goal to tear the opponent from the saddle or bring him to the ground. It is a lot more sophisticated than that might sound, with points awarded during the match for various designated moves and fouls. This takes place in a special circular 15m diameter field. Long-distance horse racing was held in the Kazanat hippodrome, and three courses were run, at 11km, 18km, and 25km. Then there was Kokpar, one of the most popular Kazakh traditional horseback team games that uses a goat dummy to score goals. The Kazakhs reigned supreme in this game, and it was by far the most spectacular event over the course of the whole Games – filled with raw energy and accompanied by the roars of the crowds as the age-old nemesis Kyrgyzs played the Kazakhs in one of the greatest finals. A few fights broke out and the police presence increased, but then again, this was the nationalistic equivalent of an England v. Germany football match – unimaginable without a certain amount of crowd rivalry. The losing Kyrgyz side later filed a motion against unfair judging and offered a replay with the same teams to once more decide the winner in kokpar.

Various national types of hunting with birds were also in the programme; possibly the most magnificent bird of prey is the Asian golden eagle, berkut. There was more, of course, and the logistics and the schedule allowed the visitor to see very many different events. At the previous games in Iznik there were a few problems in this regard; for instance, it was not possible to travel to another site for clout archery due to the lack of transport. Clout archery was not included in this year’s programme, neither was the traditional Korean 145m shooting, but the archery programme was saturated enough, both for ground and horseback disciplines.

Ground Archery

A total of 180 athletes, 120 men and 60 women, from 33 countries took part in these contests, and for contrast, the number of ground archers exceeds the cap of 128 at the Olympics. But unlike the even gender split we saw in Paris, here the ladies were at a disadvantage. The WNG registration caps required the team composition from each country to be 6 men, 4 women, 2 coaches, and 1 referee. The team event demanded 3 men and 2 women. On September 12, the final day, 16 teams registered, with Australia clinching a surprise victory.

Ground archery was contested at 4 events: Turkish Puta target – 60 m (women) 70 m (men), Kazakh Qalkan – 50 m (women) 60 m (men), Kazakh Zhamby – (women and men) – 30 m, and Team Zhamby – 30 m (team line-up: 3 men, 2 women). All archers had to wear the traditional attire of their native country, and only equipment made out of traditional materials was allowed – so no carbon arrows.

Puta had archers shoot 7 sets of 9 arrows, with the time limit of 3 minutes allotted for a set; Qalkan had 7 sets of 7 arrows, with a 3 minute timing per set; Zhamby featured 5 sets of 5 arrows per set, with the time limited to 1.5 minutes per set. In contrast, the Team Zhamby event followed the Olympic system. Each of the five team members had to shoot 3 consecutive arrows per set, giving way to their teammate. Here the time limit was 5 minutes per team, meaning that each member has 1 minute to shoot 3 arrows, 20 seconds per arrow, as per World Archery timing.

The Kazakh Zhamby target was most interesting. It is shaped like a three-dimensional golden medallion, hung up above ground at the heart’s height. The medallion is covered in golden foil and measures at 25cm in diameter and 15cm width. The free-hanging object is attached to the wooden frame and can be hit on the side, so the key objective is to ensure the arrow sticks and stays in the target. The main difficulty is that it is constantly rotating, and, as luck would have it, both Zhamby days were very windy, adding to the challenge. However, overall, the weather was “unusually summery” as I was told, “because normally it is almost winter here by now”.

Traditional Horseback archery

Traditional horseback archery saw smaller team line-ups with 4 athletes, 2 coaches, 1 referee, and only allowed one athlete per discipline. Four styles were run along the 100m track, Korean style, Turkish style, Hungarian style, and Kazakh style (zhamby atu).

Athletes were given 6 attempts at the Hungarian track, with 20 seconds time to complete the course, all points from 6 rounds were added together, with points taken off or added if time was exceeded or beaten. In the Hungarian track athletes shot 3 targets in a row, starting from the 50m start line. The Korean track gave two attempts and likewise awarded or deducted points based on times run; here 14 seconds were allotted per round. The Korean track had three stages with rearranged targets and varied task complexity. The Turkish track followed the same principles as above, and was divided into two stages, shooting at three level targets and the more challenging Kabak round, where archers shoot upwards at a 45° angle; 14 seconds were given per run. Lastly, the Zhamby track featured the same golden medallion type target as described in the ground archery section; here athletes ran 4 attempts, at 14 seconds per run. There was another surprise here with the French Raphael Mallet winning the Kazakh track.

An extra Taytuyak round was offered for the participants who ran all 4 tracks. This is one of the native and ancient types of horseback archery games. The Taytuyak is a metal object resembling a horse’s hoof, 12 cm in diameter, suspended at a height of 4 meters on three strands of horsehair, 7 metres from the track. A draw is held to determine the order of participants in the competition. Participants shoot at Taytuyak with the aim of cutting the horsehair and dropping the Taytuyak to the ground. If an arrow hits the Taytuyak but does not cut it down, the participant is not deemed the winner and the competition continues for all participants until someone cuts the horsehair. The competition’s winner receives the title of Surmergen, is awarded the Taytuyak, a belt, and a valuable gift. Surmegen is a name for one of the most prominent hunters in a folkloric tale, and is a very honourable title awarded to the most accurate and prolific archer.

Unlike in the ground archery events, where all participants were mandated to wear traditional costumes, here, given the nature of the sport and its requirements, the riders were allowed to wear specialised sports clothing as well as the national sportwear. Bows and arrows had to be traditional of course. All horse breeds were allowed at horseback archery events.

Symposium on Traditional Archery

The scientific forum addressed many interesting topics. However, of most importance for archers is the special closed session that was held in a smaller conference hall on the vast territory of the National Museum of Kazakhstan. The special session was moderated by Rustam Muzafarov, deputy chairman of the Kazakhstan National Committee for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage (KNCSICH). Events of this kind are so important for the sports on the ground, because it is here that the traditional practices are under scrutiny, and their fate and future are being decided. The overall tone of the panel discussion was serious, with some occasional humour to lighten up the mood. The moderator did an excellent job at bringing the speakers back to the topic of discussion. There were two speakers from South Korea, who appeared to have come as separate members; Park Gun, a university professor, spoke on the modern significance of Korean Traditional Archery, and the director of strategic development division from UNESCO Korea, Kim Deok Soon, talked about the organisation’s activities and their relation to broader cooperation with other central Asian colleagues. Aigul Khalafova, UNESCO Culture Programme officer in Almaty, presented some interesting ideas on projects that may strengthen cooperation and knowledge exchange between the international parties. Ayim Tlepbergen, representative of the Traditional Archery Federation of Kazakhstan spoke on the subject of the significance of traditional archery and its role today. Alisher Ikromov of Uzbekistan, director for the Development of International Cooperation, International Institute for Central Asian Studies, gave a highly informative presentation regarding the current status and issues of nomadic traditional archery in central Asia, and spoke of the commonalities between the cultures. But by far the most absorbing presentation was given by the member of the board of directors of the Turkish Traditional Archery Federation, Zafer Metin Atas. He presented a vivid case study of what it actually means when a traditional archery practice is nominated as an intangible cultural heritage of humanity by UNESCO. I sincerely hope that you have read this chapter, because it is important to know the names of those individuals who are taking an active part in deciding what will become of “your” traditional archery practice. What this particular event has highlighted for me is that most countries are ready to unify and create a new governing body, much like that of World Archery, but for traditional archery. The sport of archery consists of archers – it cannot exist without them. Hence why it is important for the active participants to aim for a clearer system, one that offers a standardised approach and similar benefits and opportunities as those for the participants of the modern sports. Furthermore, this concerns the coaches and educators directly. If traditional practices wish to thrive, then clarity, transparency and discipline are required. I shall reserve my personal judgement with regards to the country or countries that are currently not yet ready for an international operation like this, but I will observe that language barriers remain a big issue. Common languages bring people closer together, and in this realm they can be considered a super power.

How did the Kazakh archers do?

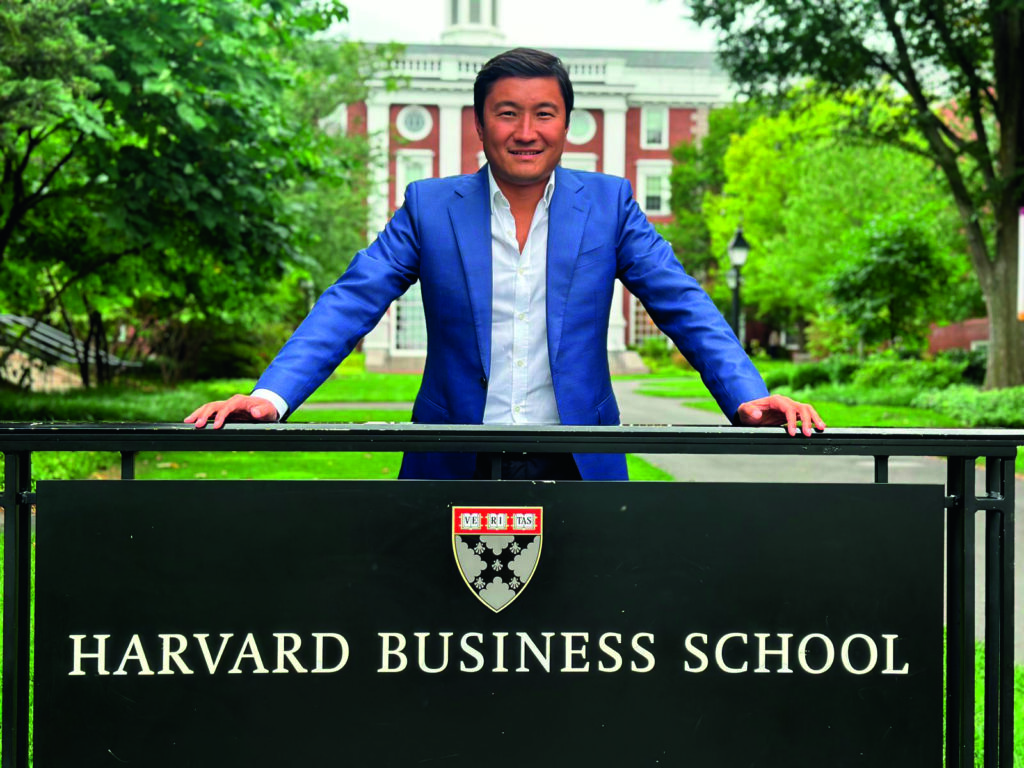

I caught up with the vice president of Kazakh archery federation and the Kazakh archery team coach, Dias Akhmetov, to get a comment on how he felt his team did:

“I think it is safe to say that in the future WNG can be a great alternative to the modern Olympic games. Ethno-sport is about preserving cultures and history, and I can certainly see that traditional practices are only gaining popularity”. Dias also said that it was not easy for the Kazakh archers, because the level of international competition is very high, and that Kazakhs who are very keen on preserving traditions, only began to develop archery rather late in comparison. “It is evident that traditional archery practices are highly developed in so many countries”, he added.

Prior to the games, the Kazakh head coach had set a minimum of medals he hoped his team would achieve, 1 gold, 2 silvers and 3 bronzes. He was happy to say that he managed to achieve that, plus an extra two bronzes.

“My team has not let me down – it is in our blood to strive to do the best in sports. What’s more, in these games all 7 gold medals for traditional archery went to 7 different countries; it goes to show that we are all on a great competitive level. Furthermore, I think these games have shown that we are not far off forming a unified international federation with the uniform rules and discipline.” Dias said that he is already starting to prepare for the next games on a different territory with the possibility of having different rules.

Budget cuts

Though the welcome we have received was of a “no expense spared” kind, costs of hosting such a vast event means there will be cuts. Kazakhstan can indeed serve as a good case study for countries that will attempt to host such big international events for the first time. I was truly impressed with the organisation, so consequently, any minor criticisms mentioned in this publication should only serve as positive criticism for future hosts. Astana’s biggest advantage was its physical scale – there was almost unlimited space, and its road system with long and wide boulevards allows great logistical efficiency at ground level.

The closing ceremony was affected by the budget cut, and only a handful of the most prominent guests in attendance were invited. It was televised for everyone else and was aired on all local TV channels. These were not the only savings that had to made. The sports programme of the 5th WNG was reduced from the original plan and all demonstration performances were made redundant. The duration of the games was reduced by one day from the original plan. As a result, competitions for ssireum, Korean folk wrestling, were excluded, and several weight categories from other wrestling events were cut. The national crowd’s favourite kokpar was reduced from 6 days to 3.

The Spirit of the People

One episode summarises the Kazakh people, and if you are into boxing, sport in which Kazakhs are very strong, you will know. Gennadiy Golovkin (aka GGG) is arguably the best professional middleweight boxer of all time. GGG, the Olympic vice-champion boasts a knockout record of 37 out of 42 fights. He is the pride of Kazakhstan and is known as one of the most simple and humble athletes around. From taxi drivers and market sellers to CEOs and businessmen, young and old, all would wake up at 3-4am to watch Gennadiy’s fights live; the whole country. That about sums up the Kazakh people, their spirit and the level of national pride.