Jaap Bolt takes us through his process

It always astonishes me when I hear phrases from regular archers like: “I don’t put much effort in my wooden arrows because they will never be as good as carbon anyway.” And even: “I never make my own arrows! Why would I?”

Yet the same archers worry endlessly about the brace height of their bow because “archery is all about consistency.” I think the importance of well-matched wooden arrows is sometimes overlooked in the trad world. Of course, many archers have no ambition at all to shoot the ‘perfect’ arrow with a ‘perfect’ technique from a ‘perfect’ bow.

Many traditional archers would argue (maybe jokingly) that’s what recurve and compound archery are for. However if you would like to find out just how accurate a traditional bow with wooden arrows can be and like to challenge yourself, then I would suggest putting a lot of effort into making your own arrows.

Another reason could be that you put a lot of effort into all the other aspects of archery, but you kind of skipped the arrow part.

So let’s say you’re shooting with a technique that’s very good and a bow that’s ‘perfect’ for you, but your arrows are quickly put together and they don’t really suit your bow and/or your shooting style, then you’re missing out. Because it’s probably much easier to make your arrows 20% better than it is to improve great technique even 2%.

The basic idea of a wooden arrow is of course not much different from a carbon or aluminium arrow. What makes it somewhat challenging is finding wooden arrows with the same weight, spine and straightness.

Needless to say you want to shoot the same projectile every time, so I highly recommend you start selecting all your shafts yourself. (Or let your supplier select them for you – but still check them yourself.) Many archers get themselves a few dozen wooden shafts based only on a spine between, let’s say, 55-60 lbs.

It is not uncommon to find that there will be under-spined as well as over-spined shafts in the batch. Personally I consider a spine variation of 5 lbs way too much and I consider myself only as an average archer. Keep in mind that spine is measured from two sides of the shaft, not one!

The difference between these sides can easily be 5lbs spine, so keep an eye out for that. I like to select shafts that are within 1lbs from the desired spine. That means if I’m looking for 54 lbs spined shafts I will take 53,01 up to 54,99.

Weight differences of 20% (!) are not uncommon even when the shafts are in the same spine range. Now imagine trying to group arrows of 580 grains, 500 grains and 470 grains at 60 yards without knowing which is which! It is fine to shoot somewhat lighter or heavier arrows, but at least group them together so you know what you’re shooting.

I select my shafts within a 30 grain range. The other vital aspect of wooden arrows is the straightness of the shaft. Wood is a troublesome material for perfectly straight arrows because of three things. First, every tree in the world grows differently and so each piece of wood has different internal stress.

Wood also shrinks when it dries, but not uniformly. And lastly wood always stays hygroscopic, i.e. it will absorb moisture from the air. Because of those three characteristics wood is always changing shape.

So when shafts are made from seemingly perfectly straight wood, it often happens that they come out bent anyway. A shaft can be bent with pressure and heat until it becomes straight, but only to a certain extent and it has a tendency to go back to its original shape. Personally I like to check for straightness on a spin tester and pick shafts that have no more than about 2 millimetres (1/12″) deflection.

When needed I also straighten them afterwards. To summarise we want to select shafts based on weight, spine and straightness and those must be pretty close to each other.

You might wonder how much work it takes to do all that: I’ve got to admit, it takes a while. Out of a batch of 100 spined shafts, I mostly find only about 20 good ones. Sometimes more, but often less.

Choosing a wood

What kind of wood you use is entirely up to personal preference, and a serious archer will have to spend some time trying everything available. Generally I’d say spruce is light but brittle, pine is strong but heavy and cedar is in between the two. People are often looking for ’the best’ choice, but I’d say that’s really personal.

To illustrate my point I’m taking my friend Jan Willem Lentjes as an example. He has a long draw length, but not a very high poundage bow. As an avid 3D archer, Jan Willem likes his arrows to have a flat flight trajectory, but a long arrow shaft means a lot of weight.

Therefore he’d rather use light spruce shafts instead of more sturdy, but heavy, pine shafts. (Luckily for him he owns an archery shop, so I’m sure he has got enough shafts to choose from!)

Total arrow weight

The priority is to match the weight of your arrow to the purpose it has to fulfil. If you were hunting, you would want a heavy arrow of let’s say 10 grains per pound of draw weight. (That means if you shoot a 42 pound bow, you shoot 420 grain arrows.)

However for 3D or field archery you are probably going to shoot longer distances and you don’t need the mass for penetration. Depending on the efficiency of your bow you could for example drop to seven grains per pound to increase arrow speed.

Especially in the primitive bow classes (in tournaments) I often see archers having to aim awfully high to hit a target at 50 yards away. No wonder, when shooting 450 grain arrows with five inch feathers out of a 35 pound bow!

They are making things unnecessarily difficult for themselves. (By the way, always check with your bowyer or store if your bow is able to shoot light arrows and what their recommended limits are.)

Tuning

Just like with recurve and compound archery, every bow is different and every archer is different and that’s exactly what makes it fun. The first thing you need to do is buy a few variously spined arrow shafts and various points and start experimenting.

You want to find out what kind of arrow leaves your bow perfectly and the way to do that is by bare shaft tuning. This means shooting an arrow that has a point and nock, but no fletchings. There are a lot of ways to check your arrow flight, but in my opinion it is most convenient to film your shot in slow motion and watch the footage.

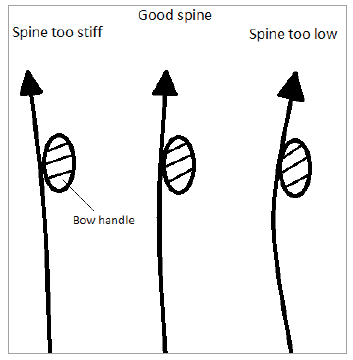

(Note that bareshaft shooting can be dangerous, so start at really close distance and always be aware that arrows can unpredictably fly off in any direction.) If, for a right handed archer, the arrow jumps to the left it is too stiff.

You should be able to see the rear end of the arrow sticking out to the right when the arrow sticks in the target. And vice versa, when the shaft is too weak it will jump to the right.

As with most arrows, to make the arrow shaft weaker you can use a longer shaft, or use a heavier point. To make the arrow shaft stiffer you can cut the shaft shorter, or use a lighter point.

When you get to the point where the bare shaft flies straight at 15 or 20 yards, you have a great starting point from which to experiment. For selecting feathers or vanes the same applies: test what works for you and matches the purpose of the arrow.

You can easily get away with three inch feathers when shooting a 55 pound bow, but for a heavy indoor arrow you might want to use five, or even six inch feathers. The same goes for point weight which also relates to the balance point of the arrow. (If you want to find out more do a Google search for “Arrow Front Of Centre”.)

A heavy point and thus a high FOC, is preferable for stability and accuracy, but a heavy point has a tendency to quickly drop and it will drag the arrow down. Maybe you want a lighter arrow or maybe you want a different balance point of the arrow. It is all possible.

Note that a well-tuned arrow shouldn’t really need fletchings to fly straight. They are only a nice extra. To conclude this article I guess the bottom line is: stop reading, start experimenting and enjoy this new hobby!

For the best field sports news, reviews, industry and feature content, don’t forget to visit our sister publications Sporting Rifle, Clay Shooting Magazine, Airgun Shooter, and Gun Trade News. And our YouTube shows The Shooting Show and The Airgun Shooter. For subscriptions, please visit https://www.myfavouritemagazines.co.uk/