Vanessa Lee says that tendinopathy is like shooting in the wind: it can be annoying but manageable.

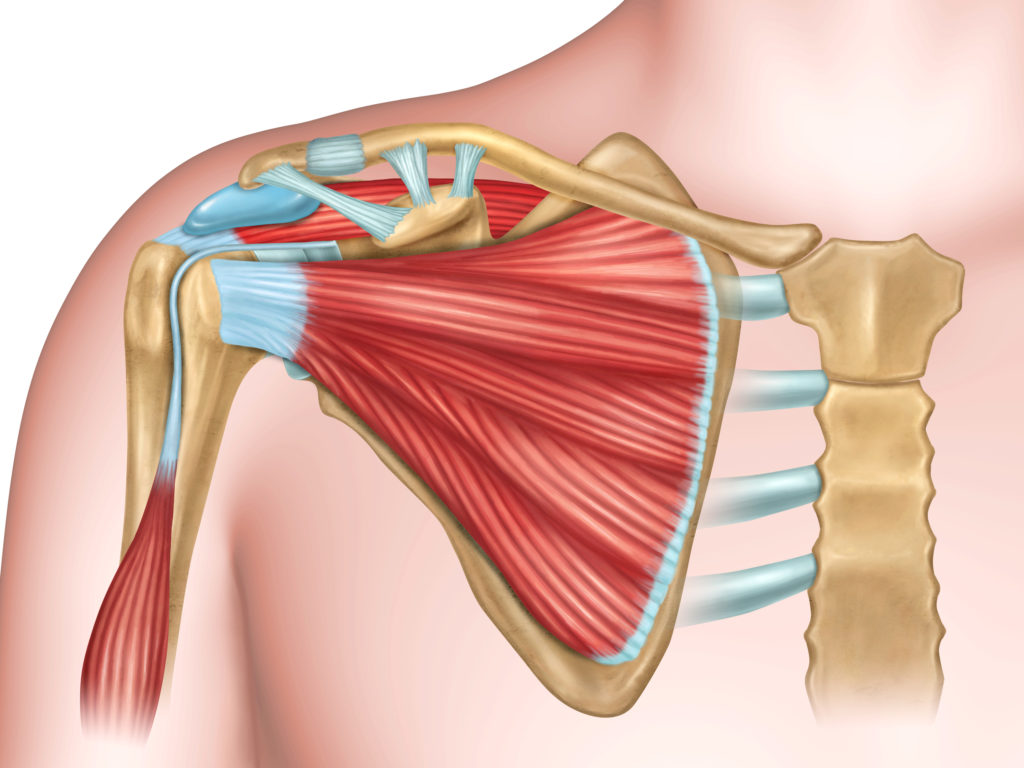

Injuries in competitive archery are common. At the 2017 Hyundai Archery World Championships in Mexico City, Oh Jin Hyek told me that he would likely spend the off-season getting surgery for his torn rotator cuff muscles. Sjef van den Berg spent the beginning of the 2018 season riddled with injuries, first in his drawing shoulder and then in his bow arm wrist. Linda Ochoa has also recently discussed dealing with her problems with her bow arm elbow as well.

Injuries among recreational archers are also very common and I receive messages daily from archers around the world dealing with different problems. One of the most common types of injuries in archery are tendinopathies.

Although tendinopathies are one of the most common types of injuries in archery, they are also one of the most straightforward when it comes to treatment.

So, what are tendinopathies? How do we get them? And, what can we do about them?

Tendinopathies

Tendons are the tougher areas of tissue that connect muscle to bone. They work by transmitting forces from muscle to bone (tensile loads) and also resist compressive forces.

Although pain is very subjective, tendon injuries often feel like a deep ache near connecting point of a muscle or generalized weakness with certain movements. Pain can be present at rest and can sometimes get worse with single or repetitive movements.

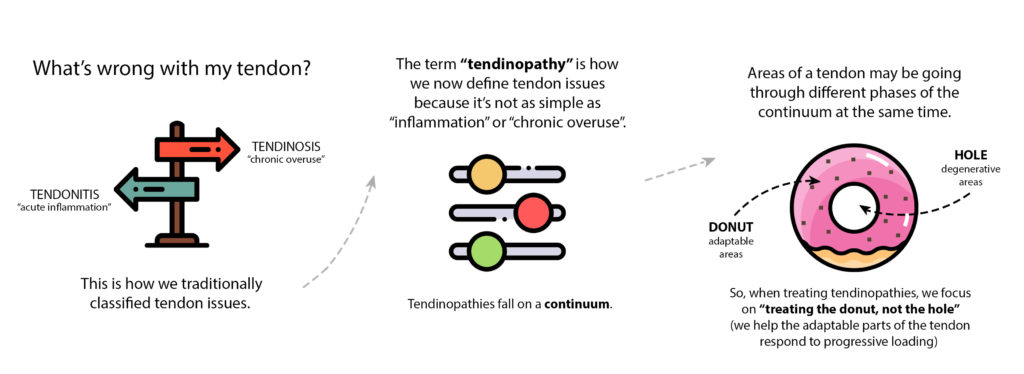

In the past, we used to categorize problems with our tendons as either tendonitis (acute inflammation) or tendinosis (chronic overuse). Instead, we now use the term “tendinopathy” because it’s a more generalized, all-encompassing name that suggests it’s not just about damage to tissues and rather, there is a general problem with the tendon.

Recent research suggests that tendinopathies fall on more of a continuum rather than a specific diagnosis related to tissue damage.

There are three main parts of the continuum:

1. Reactive Tendinopathy – acute response to tendon overload. Proteins suck in water to the tendon as a protective response to reduce force per unit area to spare tissues in the tendon at the time; changes are often reversible

2. Tendon Dysrepair – with more chronic tendon overloading, there is an increase of collagen synthesis and in-growth of nerve and vascular structures

3. Degenerative Tendinopathy – associated with signs of apoptosis (cell death), decreased collagen and matrix breakdown

Tendons often display multiple stages of the continuum at once. This is important to remember when we discuss treatment of tendinopathies. In the physiotherapy world, we like to use the analogy of a donut. Around areas of degeration (the hole), it’s still possible to reverse areas going through a reactive phase or tendon dysrepair (donut). Which is why we “treat the donut, not the hole.” We will discuss this shortly. First, a word about pain.

Pain

Pain is an alarm meant to protect you. Nociceptors (our sensory neurons) respond to stimuli by sending signals about a possible threat to the spinal cord and potentially the brain. With acute injuries that may have tissue damage, this can be really helpful because it’ll (hopefully) stop you from continuing to do something that’s painful.

When pain lingers, your “alarm” is still trying to protect you, perhaps a bit too much. That’s why pain is only sometimes related to tissue damage. It is possible that your alarm is still going off but you’ve already had enough time for your tissues to heal.

Pain is also multi-dimensional. If pain persists, it’s more often about sensitivity than actual tissue damage as different factors can make your alarm more sensitive. Things like specific movements, activities, or environments can be triggers for pain when they weren’t issues before. The good news is, since pain is multi-dimensional, there are likely many ways to help ease pain.

Often, you can deal with injuries by gradually building tolerance for painful movements. With the right kind of graded exposure, we can turn down our “pain alarm” as stressors become less threatening.

Causes

Tendinopathies occur when workload constantly surpasses an individual’s load capacity before healing can transpire. Basically, doing something your tendon is not prepared to do. Other factors like biomechanics, age, gender, and genetic or systemic conditions can make one person more susceptible to tendinopathies.

There’s actually a poor relationship between damage and pain. You may have pain but not necessarily have damage, and vice-versa! What’s more, tendinopathy imaging can’t distinguish whether a person will experience pain or not. As discussed earlier, a person’s experience of pain will be influenced by many factors such as sensitivity of the nervous system (hyperactive alarm system), beliefs, past injuries, sleep and fear, to name a few.

Some examples of workload surpassing load capacity in archery are increasing bow weight without adequate training, slapping on too many stabiliser weights without doing the prep work, increasing volume of arrows without allowing for enough recovery, etc. Although the body is quite resilient and does its best to adapt to stressors, it’s possible that certain loads can be too demanding before the body has time to get stronger.

We’ve talked about pain. It’s an alarm meant to protect us. We’ve talked about tendons. They primarily transmit and resist loads. We’ve talked about tendinopathies. Changes to tendons fall on a continuum. And we’ve talked about why tendinopathies occur. So, finally… let’s talk about what we can do about tendinopathies.

Rehab – Phase 1

There are two main phases when dealing with tendinopathies: calming pain down and building capacity back up.

Here are four strategies to calm down pain:

First, try to reduce load by lowering your bow weight, shooting fewer arrows or taking off a couple weights from your stabilisers (it all depends on where your injury is).

Second, isometric exercises may be helpful in decreasing pain. Once you know which tendon or action is causing pain, try loading the area by holding that position. For example, if lifting your arm out to the side past 90 degrees is painful, try moving to a more pain-free area and hold a band or light weight out to the side.

This is an isometric muscle contraction. Current research is mixed on the effectiveness of isometric exercises for pain but some may find it helpful. If anything, isometrics can help you reduce what is called cortical inhibition or involuntarily avoiding the use of a muscle.

Third, things like ice or heat can also sometimes help decrease pain but they likely won’t make any significant structural changes to your tendon.

Lastly, keep moving. Although it might seem like it would make sense to rest your tendon, the truth is it won’t help your tendons adapt. Continuing to move within tolerance and modifying your activities is better than completely resting your tendon.

Rehab – Phase 2

In the second phase of tendinopathy management, we want to build it back up. Now, we’re talking about increasing your tendon’s capacity to tolerate loads, which is done by maximizing how much we load it while letting it recover. Remember “treat the donut, not the hole”?

By progressively loading your tendon and allowing it to adapt, the healthier, viable areas of your tendon will increase its capacity and gradually become more resilient. That’s why passive treatments that claim to fix or heal degenerative tissue rarely work in most tendinopathies.

Now that we’ve completed Phase 1 and the pain has calmed down a bit, it’s time to start loading the affected tendon. Traditionally, it was thought that eccentric exercise (lengthening a muscle under load) was the main way to manage tendinopathies. However, current research suggests that the type of contraction is not as important as the intensity of exercise.

At the beginning of this article, I mentioned tendinopathies are one of the most straight-forward injuries to rehab and here is why. You know which exercises you need to do based on what was previously painful or difficult to do. Let’s continue with the example of lifting your arm out to the side.

If lifting your arm out to the side was previously painful or difficult, that is exactly how you’ll be doing your exercise, but now with weight and/or resistance. If bending your wrist upwards was previously painful or difficult to do, bending your wrist upwards is how you will do your exercise.

How do you know if you’re at the right intensity? You can use a Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE), which is a subjective measure out of 10 to describe how hard you feel you’re working. With tendinopathies, you’re aiming for a high RPE. I haven’t found research that recommends RPE higher than 8/10, as long as it’s a gradual progression in loading.

How do you know if you’ve done too much? Some experts that deal with tendinopathy management suggest monitoring symptoms 24-48 hours after exercising. If you experience an increase in symptoms or early morning stiffness, you should modify how much you’re loading your tendon.

You can think of loading as some sort of stress applied to our finger. Too much stress, you might get a blister. With the right amount of dosage and recovery, you might end up with a callus, or skin that’s better prepared to deal with the same stress in the future. That’s why the amount of loading is very important. Calluses need to build up slowly and this takes time. Tendinopathies will also take time – so remember to be patient!

Remember, pain does not always mean damage. Some pain is often part of the process. For guidance, find a healthcare practitioner that understands pain and can also individualize your rehab program. It’s also important to remember the important role of recovery. You can help optimize recovery by considering several things like sleep, nutrition and psychological factors.

In summary, the goal of tendinopathy management is to increase your tendon’s capacity. With the demands of our sport, we can’t always prevent injuries but we can do our best to recover and eventually minimize our risk against them.

Disclaimer: This is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. Seek out a qualified healthcare professional with questions regarding your health or medical condition.

My pain is in the area below the collar bone on my bow arm side (holding). Are there different exercises to do for this area?