While not widely known as having an archery culture, the Vikings nevertheless counted archers and bowyers among their number, says historian Jan Sachers

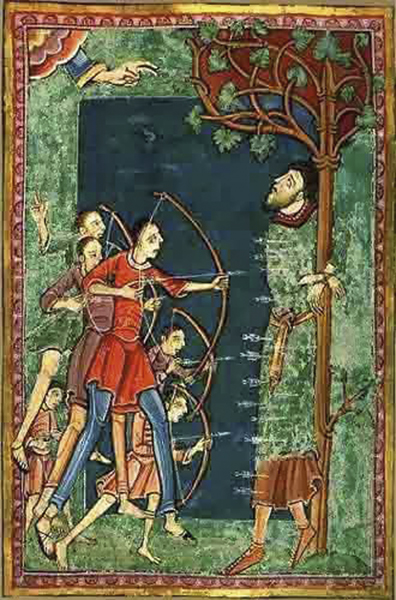

From The Life and Miracles of St Edmund, 12th century, this image shows Edmund shot by Viking archers

Bows and arrows may not be not the first weapons that come to mind when we hear of Vikings. But literary, pictorial, and archaeological evidence suggest that they played a major role in both hunting and warfare of the Scandinavian peoples during the early middle ages. There even appears to have been a distinct and somewhat peculiar type of ‘Viking bow’ – reasons enough to dig a little deeper into the history of Viking archery.

The origins of the word ‘Viking’ are uncertain. ‘To go on a Viking’ probably meant to take part in a raiding expedition, and this is exactly what the young men from Denmark, Norway and Sweden did. In their longboats they crossed the North Sea and made landfall on the shores of the British Isles, to loot and burn monasteries, towns and villages, kill all who stood in their way, and enslave the rest. From their first raid on Lindisfarne in 793 AD until 1066 AD when their descendants from Normandy won rulership over England, the Vikings instilled fear and terror in the peoples of Europe. However, in this tale of bloodshed, loot, rape, and other atrocities, it is often overlooked that the Vikings were also peaceful merchants, skilful craftsmen, keen explorers, bodyguards to the emperors of Byzantium, and successful state-builders in Russia, Sicily, Ireland, Normandy and elsewhere.

While other contemporary European sources mainly focus on the violent exploits of the heathen devils from the North, the Scandinavian sagas tell the stories of their kings and heroes, and legal documents reveal details of viking society and jurisdiction. The oldest Norse collections of laws, like the Norwegian gulathingslov for example, mention spear, sword or battle-axe, and shield as well as bow and arrows as the weapons of any free man. Among the famous archers whose accomplishments the sagas recount in great detail was a man named Einar Eindrideson, called Tambarskjelve, or ‘Flutterstring’. Around the year 1000AD, or so it is told, he competed in a flight shoot against his king Olav Tryggvarson and shot an arrow over more than 1,500 yards. In the sea battle of Svold, Einar’s bow was hit by an enemy arrow. Snorri Sturlusson, who recorded this story in the early 13th century, goes on to say that the King then gave Einar his own bow, which the seasoned archer found ‘too weak, too weak for the bow of a mighty king’.

The sagas sometimes also mention hornbogi, ‘hornbows’, mainly in the hands of the Vikings’ enemies. Short, reflexed composite bows made of layers of horn and sinew on a wooden core are generally associated with mounted archers from Eastern steppe cultures such as the Huns, Avars, Magyars, or later the Mongols. However, such bows have also been discovered in distinctly Viking contexts, for example as grave goods, and they may have been acquired as gifts, by trade, or as spoils of war.

Recent excavations at the Viking-age settlement at Birka in Sweden, for example, revealed evidence that Eastern-style archery was practised by local warriors. Not only do some of the discovered arrowheads show distinct steppe designs, leather remains also suggest that gorytoi, bow cases used by mounted archers since Scythian times, have been in use there, and among the finds was even a thumb ring, worn to protect the thumb when shooting in the somewhat mis-labelled ‘Mongolian’ style.

However, these items were imports of one kind or another, and not manufactured locally. What then did the typical Viking bow look like? Fortunately, a number of medieval illustrations give us a good first impression.

According to legend, Edmund, king of East Anglia, was killed by Danish invaders on 20 November 869 AD because he refused to renounce his Christian beliefs. The church later declared him a martyr and his death was not only recorded in text, but also in images. They show the king tied to a tree, being shot at with arrows by Danes using wooden longbows with their tips bent towards the archer. The strings are fastened to the bow just below this peculiar bend.

Similar bows in the hands of Northern warriors can be seen in a number of book illustrations from the 11th to the 14th centuries, and also in other media. For example Ullr, the Norse god of winter and of hunting, appears to carry a bow of this type in a stone carving from Balingsta in Sweden.

Ullr, the Norse god of winter and hunting, depicted on skis with a bow on the Böksta runestone near Balingsta, Sweden

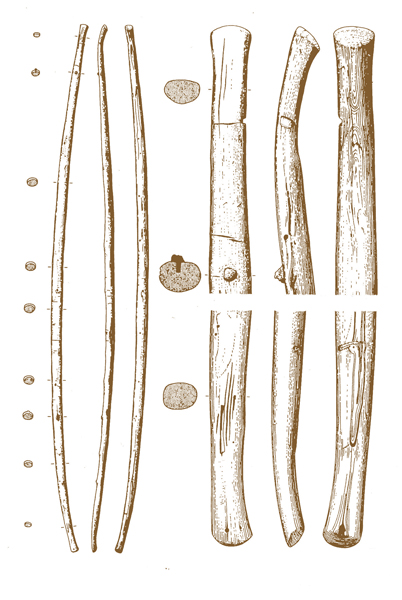

Archaeological excavations in the 1960s in Ballinderry in Ireland and Hedeby in Northern Germany unearthed complete bows and fragments dating from the 9th to the 11th centuries, which prove that these depictions were not mere artistic fantasies. The Ballinderry bow is 185cm long, 3.8cm wide in the centre and 2.85cm thick. The complete bow from Hedeby measures 191cm in length, with 4cm maximum width and 3.3cm thickness. Both artefacts, as well as some of the Hedeby fragments, show the characteristic bend and were made, with one notable exception, from yew. Very young trees of no more than 6cm in diameter seem to have been stripped of their bark and used to build these bows. They are D-shaped in profile, with a thin layer of sapwood on the back. From the grip section in the centre the limbs taper slightly down to the bend, from where the tips widen again.

Both bows and two of the fragments have a single string notch cut into their right side just below the bend. Signs of wear suggest that the string had been tied to the lower end with a complicated multiple knot. The length of the string measured 178cm for the Hedeby bow, and 169cm for the bow from Ballinderry. Another peculiar detail is a short iron nail with a domed head driven into the back of the Hedeby bow, and one of the fragments some 10cm below the nock. It was probably meant to keep the string loop from sliding down when the bow was unstrung.

The bending of the tips was most likely achieved by steaming the wood. In its moist, hot state the stave could then have been fixed on some form of rig or bent around a cylindrical object of sorts. But why exactly the Viking bowyers would go through such extra efforts is somewhat enigmatic, though. The bent sections have no purpose; they offer no mechanical advantages whatsoever, and in fact only serve to increase the mass of the limbs without adding to their strength. If they were not simply a cultural feature or tradition, their only possible explanation was to act as handholds when stringing the bow.

Modern reproductions of the Ballinderry and Hedeby bows have proven themselves to be very effective weapons of between 80 and 100lbs of draw weight – but these measurements refer to the modern standard draw length of 28 inches. If the medieval images are realistic representations of Viking archery, then their anchor point was at the chest rather than the chin or the ear, resulting in a shorter draw, particularly considering the shorter height of medieval man.

Sadly, no complete Viking arrow shafts that could give an indication of their draw length have been discovered yet. Shooting distances of 1,500 yards as recorded for Einar Flutterstring are out of the question anyhow, merely the stuff of legend. Even the 13th century Icelandic laws defining a bowshot as a measure of distance of roughly 525 yards seems a little far fetched. But armed with a broadhead, an arrow shot from a viking bow would without doubt have had sufficient power to penetrate leather, skin, flesh, and potentially even soft armour, at reasonable distances, making them formidable weapons for both hunting and warfare and thus very suitable arms of a free man.

When William, duke of Normandy, crossed the channel in 1066 AD to conquer England, he brought with him a substantial number of archers. The battle he fought with king Harold at Hastings is recorded on the famous Bayeux Tapestry. The bows carried by the Norman archers appear to be a little shorter than the earlier Viking bows, but still appeared to be following the same building pattern. The accuracy of these depictions has long been in doubt, but the 1986–1992 excavations in Waterford, a town in Ireland founded by Vikings, unearthed one complete bow and six fragments showing great similarity with the ones shown.

The 11th century Norman bows depicted in the Bayeux Tapestry still show the characteristic shape of the earlier Viking bows

They were made of yew, with the characteristically bent tip section, but the complete bow only measures 126cm in total length. A single string notch was cut into opposing sides on the upper and lower end respectively. Apart from a great number of arrowheads, a lot of them bent, one complete, unbroken arrow 23.8 inches long was also found at Waterford. The finds are probably connected to the town’s capture by the Anglo-Normans under Richard Fitzgilbert de Clare, better known as ‘Strongbow’, in the year 1170 AD.

It would seem the Viking bow was still – with some adjustments – very much in favour after a couple of centuries, apparently having proven its efficiency satisfactorily.

If you’re interested, here is a short list of some further reading on the subject:

Juergen Junkmanns. ‘The Bows of the Vikings’ in: The Bow Builder’s Book. European Bow Building from the Stone Age to Today. Atglen: Schiffer Publications. 2nd ed. 2012.

Michael Leach. ‘The Norman Short Bow ‘ in: Journal of the Society of Archer Antiquaries 52 (2009), pp. 82–90.

Harm Paulsen. ‘Pfeil und Bogen in Haithabu’ In: Harald Gelbig and Harm Paulsen. Das archäologische Fundmaterial VI. Berichte über die Ausgrabungen in Haithabu. Bericht 33. Neumünster: Wachholtz Verlag 1999, pp. 93–143.

Thank you allot for all the Info really helped!

nice article… thanks

Thank you a very interesting article

Actually we have at least one respected archer. The son of Ragnar Lodbrog, Ivar Benløs. He was known as an excellent archer, and I believe it was him who shot “troldkoen” (a magical and terrifying cow which some Norwegian king had. Though I do not have my collection of sagas handy.).

Do you happen to have the source for the gorytoi found at Birka?

Could the little nail in the Haithabu bow be intended as a “stopper” for a stringer? Just enough of a bump to prevent the string sliding up on the limb?

We know the etymology of viking. Coming from Vík “small inlet or bay”. -ing is a termination denoting a person or peoples. So “people from the small inlets or bays”.

Geirr T. Zöega defines the fem. verb as “freebooting voyfemale. “Hann var í viking á sumrum ok fekk sér fjár”. He was on a “expedition” in summer and got himself rich.

The masc. Noun is “víkingr” meaning person who does said verb. “Floki Vilgerðarson hét maðr, hann var víkingr mikill”.

“There was a person named F.V. he was a great viking.

If you look at the Heimskringla – The Norse kings saga, archery is named as an importaint skill. And there are numerous references to archery during battles. Probably the most famous archer we know of from the Viking age would be Einar Tambarskjelve (shaking bowstring). He was knows as a master in archery, and was said to be able to shoot a blunt arrow through a wet ox skin.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Einar_Thambarskelfir

Or if you want the full story, read about him in Olav Trygvasons saga in Heimskringa. You can find it online in English.