Archery was used for hunting and warfare for centuries, but that didn’t stop archers having fun with it too, as Jan Sachers reveals

In this painting ‘Diana and her Nymphs’ by Domenichino (c. 1620) you can see the target bird and, on the left, trophies hung from a pole

Sporting competition has always been a part of archery history, ever since early man first challenged his fellow archers to shoot farther or faster or more precisely than him. Apart from being enjoyable, recreational pastimes, various forms of target archery and distance shooting have traditionally served to train and prepare archers for their tasks in hunting and warfare. On 1 June 1363 King Edward III issued his often-quoted edict, mandating ‘… that every able bodied man on feast days when he has leisure shall in his sports use bows and arrows, pellets or bolts, and shall learn and practice the art of shooting’, and at the same time abolishing football ‘and other vain games of no value’ – what a wise ruler! Sadly, he did not specify in which way his subjects were expected to practice their archery.

Shooting at the butts was probably the most common form of archery practice in medieval England. “Butts were man-made earth mounds, clad with turf and given a rounded roof, so that water would run off and they would be able to stay out in all weathers. […] They were permanent features in towns and villages,” says Mike Loades in his 2013 book The Longbow. Usually set up in pairs, so that they could be shot at both ways, the butts certainly made for a good, cheap (or rather, free), and long-lasting target.

Roving was another popular form of archery throughout the Middle Ages and probably long before. One archer designated a natural object – a tree stump, an ant hill, a dark patch of earth, a pile of leaves or the like – as a target, and every participant shot one single arrow, trying to hit it or at least get as close as possible. The winner was to call the next target, and so on.

However, the medieval battlefield was a place very different from a quiet and peaceful village common or the pleasant green countryside, and military archery required a different set of skills than target archery. How then did medieval professionals like the famous English longbow archers train?

One of the earliest literary references to an archery contest can be found in Homer‘s Iliad, written some time around 800 BC. After the death of his friend Patroclus, the hero Achilles holds a feast for his funeral which includes, among other things, a competition with bows and arrows. A living pigeon is tied to the top of a ship’s mast, and whoever hits the bird is promised 10 great double-bladed axes. However, hitting the thin thread with which it was bound is only considered worth a number of smaller, single-bladed axes.

Teucer, known as a great archer, shoots first, but his arrow cuts the thread. Meriones grabs the bow off him, promises an offering to Apollo, the Greek god of archery, and promptly hits the bird in flight, thus securing his victory with divine help.

We have no way of knowing whether this form of archery practice was common in ancient Greece, since there are no other surviving texts or images relating to it from that time. There is evidence, however, that shooting at the bird, or ‘popinjay’, as it is most widely known today, became a very popular form of practice in the late Middle Ages, first among archers, then crossbowmen as well.

Mike Loades in his recent book The Longbow mentions an early 14th century depiction of a contest, with the bird fixed atop the sail of a windmill. The Kilwinning Archers still hold an annual popinjay shoot that dates back to the 15th century, with the target – originally a live bird, later a wooden one – suspended from a horizontal pole extending from the clock tower. Many 16th and 17th century paintings and book illustrations show both archers and crossbowmen shooting at a live or wooden bird fixed at the top of a tall pole.

A Swiss mandate of 1659, which abandoned the use of bows and crossbows in favour of the more modern firearms, explicitly states “… that it has always been the purpose of these competitions to train the militia in the use of weapons and prepare them for military deployment.” Being able to shoot upwards at a steep angle and hit a small target was essential in medieval naval and siege warfare.

Often overlooked in favour of the great and famous land battles like Crécy and Agincourt, the Hundred Years‘ War (1337–1453) was also fought at sea, and archers aboard sailing ships played an important role in this. Not only were they needed to sweep the decks before boarding an enemy vessel, but also to pick individuals high up in the rigging or in the crow’s nest, often archers or crossbowmen themselves.

Pieter Brueghel the Elder’s ‘The Fair of Saint George‘s Day’ (c. 1559-62) shows bird shooting in the background left

In the siege of a town archers, crossbowmen, javelin throwers or men hurling great rocks from atop the battlements posed a great threat to the attacking army. Hence archers were deployed to pick them off one by one, which was not an easy task, since the crenellated walls made it easy for a man to hide behind the stonework. But whenever a face appeared in an opening, it became the target for the besieging archers, who had probably prepared for this feat by shooting small birds off a high pole.

Ballistic or artillery shooting was commonly used in the early stages of a battle. Mention of ‘a hail-storm’ or ‘showers’ of arrows – so densely packed they blacked out the sun – can be found in historical accounts from Herodotus in the 5th century BC to the Hundred Years’ War. Again, this was a tactic also used in siege warfare, sending a volley of arrows over the battlements, to discourage the enemy from forming defensive lines atop the walls and starting a barrage of their own.

The ability to judge distance accurately and deliver a precise shot over a considerable range is reflected in two archery disciplines that became very popular during the 16th century, but are probably a lot older. In clout shooting the target was originally simply a scrap of cloth (‘clout’) pegged to the ground at a distance of 160 to 240 yards. Later, a circular target made of canvas, 18 inches in diameter and stuffed or backed with coiled straw was used, fixed to the ground by a wooden peg in its centre, called ‘the prick’. The aim was to hit the target, but to ‘cleave the prick’ was considered a very rare and special feat, no doubt worthy of a celebratory extra round of drinks or two.

In shooting at the marks distances varied, like in roving shooting, but the principle was similar to that of clout shooting. The marks were wooden posts spread over a large area and often obscured by natural obstacles such as hedges, a group of trees, the brow of a hill or the like, the layout somewhat reminiscent of a golf course. Ballistic shooting was once again required in order to get one’s arrows as close as possible to the mark, but this time, distances had to be estimated accurately as well.

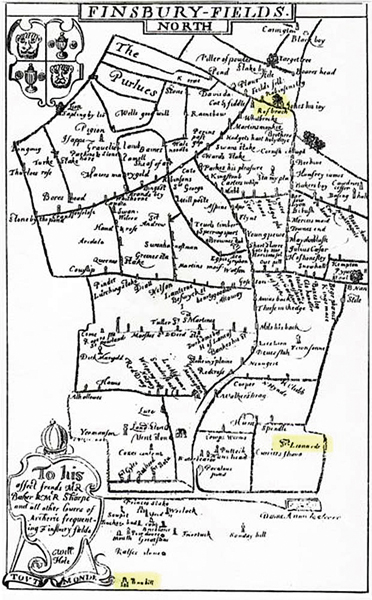

In 1498 an area of 11 acres in London, known as Finsbury Fields, was designated by the mayor of the city for the practice of archery. It became the home of the Fraternity of St George, which later changed its name to The Ancient and Honourable Artillery Company – the very name reminiscent of the kind of archery mainly practiced there – which in turn formed the nucleus of the Finsbury Archers, formed in the 1590s. A rare map of Finsbury Fields from that time shows no less than 194 different marks, with distances ranging from 130 to 345 yards.

Another once popular archery game, of which next to no written records survived, was wand shooting, or ‘splitting the wand’. The wand was a wooden pole or lathe, anything between two and five inches wide, stuck into the ground at a certain distance from the archers, sometimes a few feet in front of a butt as an arrow stop. With the narrow target standing up to six feet tall, judging distance correctly was not as essential as precise aim, taking side winds into account, and a clean release, so the arrow would not stray sideways. It is conceivable, though by no means proven, that wand shooting had originally been a method of training to send arrows through the narrow vertical openings of loopholes or arrow slits in town or castle walls, once more emphasising the important role of archers in sieges.

Unlike popinjay, which was popular throughout most European countries, particularly Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany, and Switzerland, the other forms of archery described here appear to have been practiced exclusively in Britain. Today, many of them are rediscovered by traditional archers looking for alternatives to target shooting or the 3D course. Clout shoots and marks in particular enjoy increasing popularity once again, offering the great joy of watching one’s arrows fly gracefully over long distances.

Thankfully, these can now be enjoyed as mere recreational pastimes, without the need to prepare for fighting in sieges, battles, or other forms of war.