Hugh Soar takes a look at bow making traditions from Scotland, France and Belgium

The tradition of Scottish bow making, both longbows and crossbows, is ancient and honourable. Makers of hand bows – in Scotland called ‘bowers’ or ‘bowares’ – are first mentioned in Edinburgh burgess records in 1445, when John the Bower appears; he is preceded in 1435 by Nicholas Hude, arrow maker – paid 53s 6d (Scots) to make 32 sheaves of arrows for the King.

Scottish bow and arrow makers, once entered as City burgesses, were ‘incorporated’ into a Guild, organised in similar fashion to those of their respective trades in England. Unlike their English counterparts however, most Scottish bowers also made arrows and other equipment unrelated to archery; spear shafts, clubs and gun stocks appear across the centuries among work undertaken by them.

Notwithstanding the combination of trades, arrow makers alone do occasionally appear among the records, such as: ‘Johne Ra, and Johne Fairbyrne fleggearis’ (fletchers), James Clark in 1560, Robert Spence in 1582, Richard Walker ‘Inglishman, in town (Edinburgh) for teaching his art’, and Berty Wardlaw who added bowstrings and blunt bolts to his itinerary.

Wills are often explicit of activity. The 16th century effects of John Gibson, bower of Edinburgh, included 50 bow strings together with 100 ‘small bowstrings for bairns’, 5,000 of ‘arrow timber’ and 20 ‘drest’ bows for men and 40 for bairns. George Tait, another 16th century bower, left 10 made bows ‘part glewed and part unglewed’. ‘Sessonit’ (seasoned, presumably waxed or glued) and ‘unsessonit’ strings are also mentioned.

The early records of Scottish bowers are interesting in their own right, but sadly no bows survive to tell of their skills. The ‘Flodden’ bow, enigmatic survivor of the battle, is held by the Royal Company of Archers who claim it for their own, although there is nothing to truly substantiate the claim since it may have come from either side. Some six feet in length, it is of self yew, and has an estimated draw weight of 80 to 90lbs. To the writer’s knowledge, no effort has yet been made to compare this relic with those recovered from the warship the Mary Rose – such a comparison would be of much useful interest.

One of the surviving – recreational – bows is an example by 18th century maker Thomas Grant; dating from about 1775, it is one of the few early Scottish recreational bows available for detailed study.

Of self lancewood, it is 71 inches long, conventionally plano-convex in section and, having no built-up handle, would have ‘worked in the hand’. It has several unusual and interesting features not found on modern longbows. It is fitted with a belly wedge, a useful device that could well make a comeback since it is designed to deflect an arrow over-drawn ‘inside the bow’. Stringing horns (nocks) are side grooved or ‘side nocked’, common to heavy draw-weight English war bows, and for which evidence can be seen on those from the Mary Rose. They are said to make stringing by hand easier. Also incorporated are ‘purging holes’, that is, holes drilled through the horn to allow excess glue to be exuded, thus avoiding build-up of hydraulic pressure, a common feature on some late 18th, and early 19th century English bows.

This bow has provenance to Blair Atholl Castle, on whose walls it hung for over a century. Its owner may have been the Earl of Atholl, whose election to the Royal Company of Archers in 1778 is noted in their history.

A second bow by Grant is known; of similar dimensions it is marked ‘S F’, believed the initials of Simon Fraser, elected to the Company in 1770. The writer possesses a pair of arrows similarly marked, formerly belonging to this archer.

The 19th century Edinburgh records reveal three ‘incorporated’ bowers. William Phin, John Sime, and George Lindsay-Rae. Nothing is known of the first two, although unmarked bows with Scottish features may be by one or the other. Lindsay-Rae, however, was officer and bower to the Royal Company between 1793 and 1818. He was commissioned by Sir Nathaniel Spens, president of the Royal Company, to create a bow in recognition of his 60th year in archery and this bow is in the writer’s collection.

The bow dates from 1810, is 68 inches in length of self yew, and of conventional plano-convex section. It has forward facing nock grooves cut in the Scottish style. A belly wedge was originally incorporated, but was removed to allow the affixing of a commemoration plate explaining the reason for its presentation, and the name of James Millar, the Royal Company archer who won it in competition.

Bow-making in Scotland will for ever be associated with two men – in the 19th century Peter Muir, and in the 20th Richard ‘Dick’ Galloway. Sadly, space does not allow of justice to the latter.

Peter Muir began his apprenticeship with his uncle David Muir, at his bowyery workshop in Kilwinning, Ayrshire, home of the legendary Papingo shoot. He became bowyer to the Royal Company in 1828 and matured into one of the finest bow makers the 19th century produced. The writer is fortunate to possess a number of his models including six men’s bows in self yew, and three in self lancewood. Each is of conventionally ‘high stacked’ plano-convex section, and each is just 69½ inches long. One early example has a belly wedge and each has the ‘spoon’ shaped nocks associated with Scottish bows. All self yew bows by Muir have ‘half-moon’ shaped arrow passes, in distinction from the ‘steeple’ shape used in their English counterparts.

Besides his evident skills at bow making Muir was an excellent archer, regularly entering the early Grand National Meetings and becoming National Champion three times, shooting the first of the double York rounds. His last success in 1863 was achieved when he was 64. He passed away in 1878 aged 87.

Muir’s assistants, William Fergie the Elder, his son William Fergie the Younger, and Andrew Gordon each succeeded him, their skills honed in his workshop. Both Fergie the Elder and Gordon marked their bows and arrows ‘late Muir’ in his honour. Thus it was that the tradition of ‘Muir excellence’ was maintained for another 47 years.

Kilwinning was also home to bower James Reid, one of whose bows, in a self exotic wood, has a most unusual double concave groove running the length of its back. It has a conventional convex belly, with an uncovered cork handle. No draw-weight is marked but it is evidently light and most appropriate to short butt shooting. It has Scottish-style horn nocks and grooves.

Although this article has touched on Scottish bows it will be interesting to look briefly at evidence of continental bow making tradition by examining three recreational bows from France and Belgium. Each country is steeped in ancient recreational archery practice, and the bows described reveal aspects that differ markedly from both Scottish and English traditions.

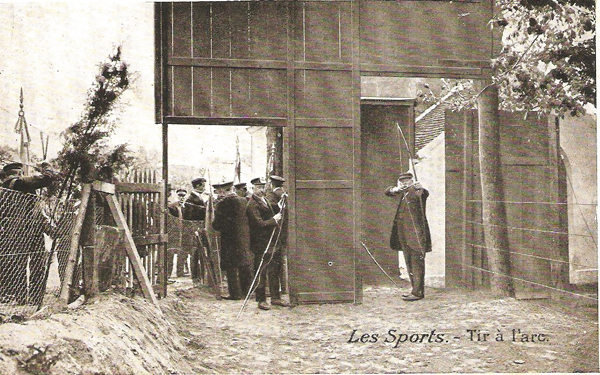

The first example is of a French ‘butte’ bow. These were used in the ‘jardins d’arc’ where ‘tir a berceau’, or butt shooting at 50 metres, traditionally took place. They were ‘take down’ bows carried together with two arrows in a ‘carquoise’ or leather carrying case.

That described was made by G. Peeboom of Ambley, in Aisne Province, and probably dates from the turn of the 19th century. It is 69¼ inches long with a striated rubber handle over a metal sleeve. It has a plano-convex section (low stacked), a belly of exotic wood and a hickory back with a multi-laminate core. Nocks are simple and of horn. Limbs are wide but shallow at the handle, tapering evenly to each tip.

The case is marked with the owner’s name – Alan Carpentier, a member of the ‘1st Companie d’arc’ in Chantilly, a club said to have been formed in 1752, to shoot ‘tir aux buttes’ at 50m.

Although France and Belgium share a border, and each shot at buttes or tir a la perche, bowyery traditions evidently differed. The Belgian bow I now describe was made by Yvon DeLavie, of Jemappes, and is an imposing 76 inches long; each limb is 2cm 5mm wide and 1cm 8mm deep, and evenly tapers. Unlike its French equivalent, it does not take apart. It is heavily deflexed and has a broad back of hickory and a low-stacked (narrow) convex belly perhaps of boxwood, with two exotic wood laminations. As with its French counterpart, no draw weight is marked. The handle is a circular metal sleeve covered with light green braid interspersed by black banding. Two Societies shot at Jemappes.

A third continental bow, perhaps French, is interesting in that each limb is demountable within a metal sleeve. Believed to be made of self greenheart, it is 56 inches long and is either a ladies, or even a child’s bow. Limb sections are plano convex and high-stacked, 16mm wide and 15mm deep evenly tapering to each tip.

Much more might be written; however I hope this article has given some brief insight into traditional Scottish archery and that of its continental counterparts.

I am a direct descendant of George Lindsay Rae and was really pleased to see the photo of one of his bows.

My Great,Great Grandfather named his youngest son after Peter Muir who was a friend of his.

( George Linsay Rae’s daughter was my Great,Great Grandmother )

I would love to know if George’s father was also a bowmaker but haven’t been able to find out.

I am looking for an English long bow, where can I get bow and arrows?

I have a bow that I’m trying to identify and was wondering if you can help point me in the right direction. I has a grip very much like the one you show by Lindsay-Rae. It’s marked by the Initials LAW above Edinburgh on one side and has a three arrows in a triangle pattern pointing to 47 on the other end of the grip.

It’s obviously hand made, approx 73″ long and has the bone tips on each end to for the string. It has a D shape to it, with a thin light colored wood on top and a darker wood that looks almost like walnut.

Any help would be greatly appreciated

Are there any chance of getting a bow 36 ins long made