Jan H Sachers glues up a history of composite bow

Over the course of history, composite bows have been built and used in a stunning variety of shapes and sizes. But they all have one thing in common: rather than being made from a single stave of wood (self bows), or laminates of several layers of similar materials (laminated bows), they were composed of three or more layers of dissimilar materials, according to W. F. Paterson’s definition in the Encyclopaedia of Archery (1984). A clever combination of natural materials with different properties offers many advantages for designing efficient bows.

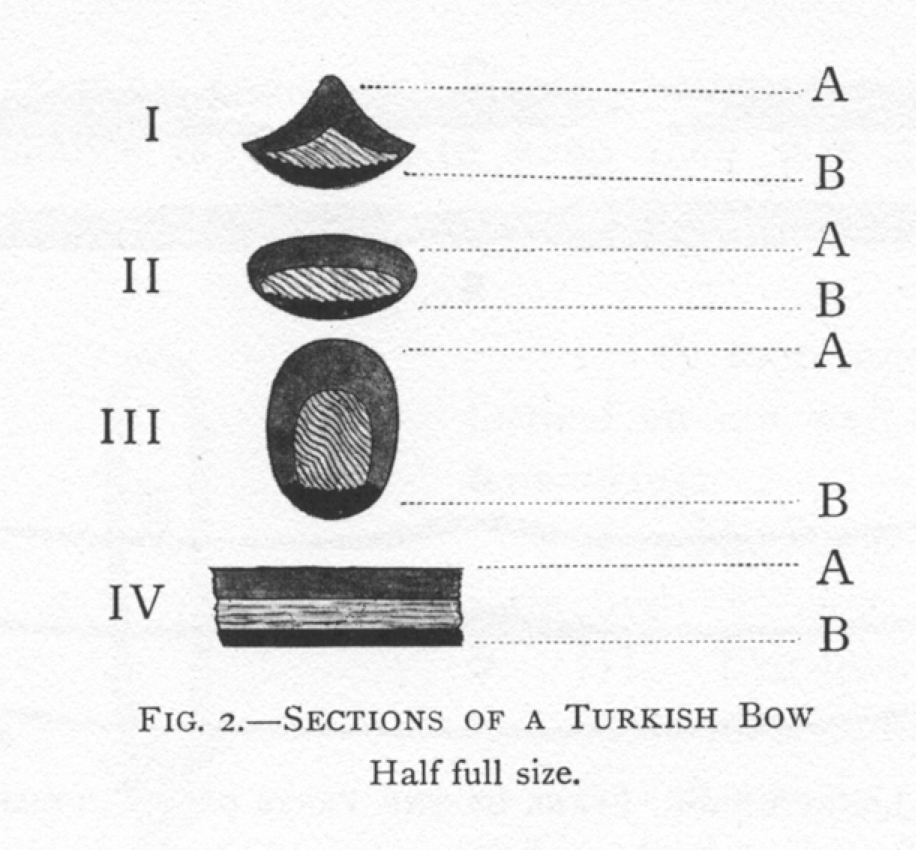

A bow is essentially a simple form of spring. When the string is pulled, the outer side of the bow, the back, comes under tensile stress, while the inner side, or belly, is compressed. In natural materials, such as wood, the amount of tension they can absorb before breaking is rather limited, which means that in order to accommodate a longer draw, the bow itself needs to be longer as well.

The draw weight depends largely on the thickness of the stave and the individual properties of the wood in use. It will increase in a steady curve from the beginning of the draw up to the point when the bow can bend no further, or simply breaks.

Mechanical advantages

Thanks to their ingenious construction and design, these limitations do not apply to composite bows. Generally, their belly consists of a layer of horn – usually ibex or water buffalo – which has excellent pressure-resistant qualities. The back is covered with one or more layers of sinew, which in turn handles tensile strain very well.

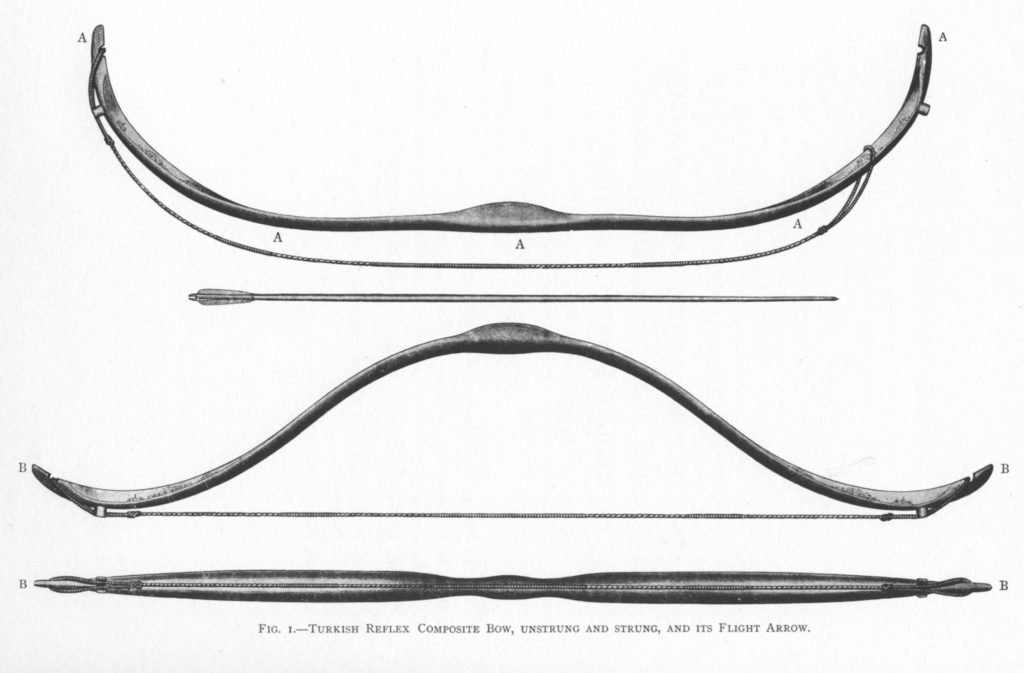

Back and belly are glued to a wooden core, which mainly lends stability and defines the shape of the bow. Rather than being straight, like wooden self bows, composite bows are usually recurved, their reflex tips pointing away from the archer in an unstrung state.

While drying, the sinew on the back contracts, sometimes up to a point where the tips touch or even overlap, making the unstrung bow a pre-loaded spring, so it will take some strength and proper technique to even brace it.

Fish glue, which was mostly used to stick the different components together, dries very slowly, so the building process could easily take one or two years, making composite bows expensive and valued pieces of equipment. On the other hand, they tend to be very delicate and need to be warmed up before bracing, may develop twists in the limbs, which need to be corrected before shooting, and are best stored in a temperate environment.

The combination of elastic materials and the recurved shape allowed for composite bows to be built shorter than self bows, yet still deliver the same, or an even greater, amount of power. Their mechanical properties are very different, though.

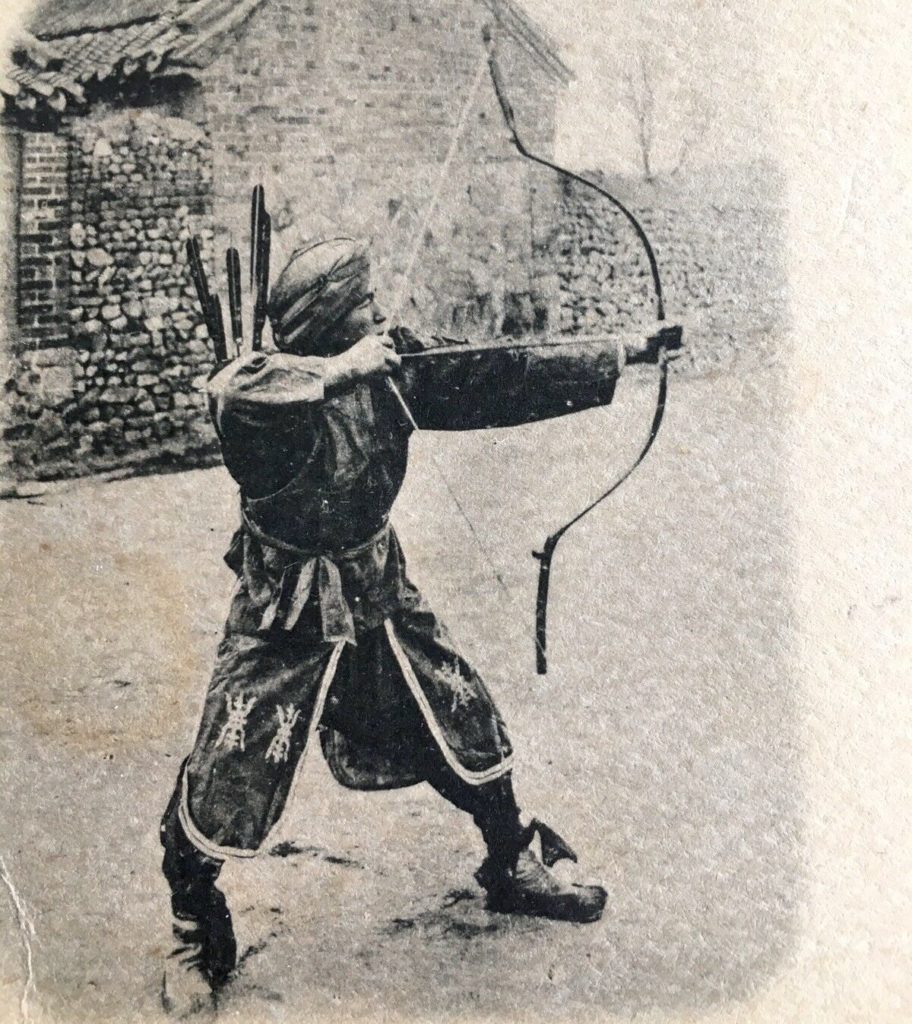

In its strung state, a recurve bow is already under a lot of tension, so the initial draw weight is higher than with a straight bow. When drawn, only relatively small portions of the limbs actually bend, while the reflexed tips act as levers, reducing the amount of muscular power it takes to pull the string further back.

This effect is magnified if the end parts of the limbs are stiff and pointing away from the archer at an angle, a feature that is known by its Arabic name, siyah. In this case, the string of the braced bow rests on so-called bridges at the knee of the angle.

At the beginning of the draw, the archer has to overcome the resistance caused by the effectively shorter string, but as soon as it lifts off the bridges, the draw weight feels considerably reduced, which is known as let-off – the same principle achieved with eccentric pulley wheels in modern compound bows.

In order to protect them from moisture, composite bows were usually covered with bark, rawhide or leather, which could be lacquered and was often beautifully decorated. That they don’t work in wet or cold climates is a myth, easily dispelled by the fact that such bows have been successfully used throughout Asia and Europe in all weather conditions.

All shapes and sizes

Composite bows are mainly associated with nomadic peoples from the Eurasian steppes and their use from horseback. We do not know for certain when they were invented, where or, indeed, why. Was it the lack of suitable wood to build self bows? Or rather the need for shorter, yet powerful bows that could be used comfortably by a mounted archer?

Most likely, experiments with various natural materials led to the invention of sinew-backed bows, which are also known from Native American and other cultures, to which a layer of horn was later added to increase their power.

The earliest known examples of composite bows are of Scythian origin and of a very particular design. They are often depicted in Greek art and have long been considered to be the results of artistic licence, rather than truthful representations of functional weapons.

But very well-preserved artefacts up to 3,000 years old were discovered in Xinjiang in north-western China and their careful examination, by authorities such as Stephen Selby, and reconstructions, by Adam Karpowicz, Jack Farrell and others, have proven them to be functional, very powerful bows.

A continuous strip of ibex horn formed the core of each limb and gave these bows their distinct shape. It was sandwiched between laths of wood spliced together, backed with layers of sinew and also wrapped entirely with sinew, then covered with birch bark. The cross section is triangular, or diamond-shaped, with the wider base towards the back. The rigid tips are curved away from the archer and the string runs in a groove along their belly side.

Very different in functionality and design from the early Scythian bows are those commonly associated with the Huns. Since horn, wood and sinew are all natural and, hence, perishable materials, only very little archaeological evidence remains of the existence of early composite bows.

Those of the Hunnic and later Magyar types, however, had the sides and sometimes also the belly parts of their siyahs and grip portions reinforced by carved plates of bone. These have been excavated in fairly large numbers, mainly in grave sites from late antiquity to the early Middle Ages and prove that such bows remained in widespread use throughout Europe, Central Asia and the Near East for many centuries.

The Hun bows were not the most efficient type, but sturdy, reliable and easy to use, thanks to their comparatively large size. Even bigger were the bows of the Manchu, who ruled in China from 1644 to 1912. They had wide limbs, long stiff siyahs and string bridges made of horn, antler or wood, and were used to shoot heavy arrows with very long fletchings.

Today’s Mongolian bows are slightly smaller descendants of this design, while the bows of Genghis Khan’s conquering armies would have been shorter, broad-limbed, with long, curved siyahs and a pronounced ridge to reinforce the section between them and the working limbs, the kasan.

Korean bows are among the shortest examples and built to an extreme reflex, with the tips often touching or overlapping in their unstrung state. Very light in weight, they were designed for extreme performance and long-distance precision with light bamboo arrows. Due to their narrow limbs and extreme reflex, they tend to twist easily and need constant, diligent care.

The same is true for what some experts consider the most advanced type of composite bow, the Turkish or Ottoman flight bow. Its name, hilal kuram, means crescent moon shape and refers to its appearance in unstrung state.

It bends almost exclusively in small sections of the limbs above and below the characteristic grip, while the siyahs and the long kasan sections below them remained stiff, enhancing the bow’s mechanical efficiency, but at the cost of its stability in the cast.

The hilal kuram was designed for long-distance shooting with special lightweight arrows. Many examples can be found in museums, often lavishly decorated. The Ottomans also used other composite bow types for warfare and target shooting, which are closely related to the Crimean Tatar bows and the wide-limbed Mughal bows, also known as crab bows.

Composite legacy

Other types of composite bows have been in use throughout history, such as the Assyrian angular bow, the Indo-Persian, the Chinese Ming bow and more – Mike Loades offers a comprehensive overview of their design, construction, qualities and use in his 2016 book, The Composite Bow.

They differed in size, shape, mechanical properties and many other details, but were all based on the same principle, the combination of the three main materials of horn, wood and sinew for optimum performance.

Although composite bows always remained a part of Near, Middle and Far Eastern archery cultures, they have been used in the West as well, acquired as loot, gifts or merchandise, traded along the famous Silk Road across Central Asia. The distinctive recurved shapes appear in medieval European artwork and remains have been discovered in Viking-age find sites, such as Birka in Sweden.

In the late Middle Ages, the technology of the composite bow was adopted by crossbow makers to construct prods more powerful than those of wood, before they were in turn superseded by ones of steel.

But, by the beginning of the 20th century, the ancient, time-consuming art of building composite bows had been all but lost, when Western archery historians such as Ralph Payne-Gallwey rediscovered it from an armchair researcher’s point of view.

By the 1930s, a lone bowyer from Germany by the name of Helmut Mebert may have been the only composite bow maker left in the world and he even patented his simplified method of making bows in the Ottoman style.

Despite its use of space-age materials, such as aluminium, glass fibre and carbon, fast-drying synthetic glues and features such as pistol grips and arrow shelves, the modern laminated recurve bow is essentially still a late descendant of the composite bow and makes use of the same mechanical principles.

Nowadays, however, more and more bowyers all over the world are rediscovering the old methods and are once more building true composite bows in the Scythian, Turkish, Mongolian or Korean styles, using nothing but horn, sinew, wood, leather, bark and animal glue to keep the tradition alive.