Jan H Sachers gets a fistful of steel as he discusses metal bows

Since the dawn of archery many millennia ago, wood has been the most common material to produce bows. In some parts of the world, particularly the Eurasian Steppes, where proper bow woods like yew or elm were not available, and archers on horseback required short, powerful weapons, a composite of wood, horn, and sinew was used instead (see Bow International 161, pp55–58).

It was only in the 20th century with the advent of new synthetic materials that preferences changed, and glass or carbonfibres were incorporated in bows or limbs. Since the 1970s, aluminium and magnesium were used to produce stiff but lightweight risers for take-down recurve and compound bows. But apart from that, metal never appears to have been considered a proper bow-making material – or was it?

Bows of steel or bronze are mentioned in the Bible, but only as metaphors for strong or unbreakable weapons. Highly ornamented metal reflex bows from the Indo-Persian Mughal empire made of damascus steel can be admired in many museums, but they must be considered as being of ceremonial use rather than actual weapons.

Since the 15th century, European crossbow makers used mild steel to produce very powerful prods, but a longbow of the same material would be very slow, very heavy, and far too strong to be pulled by hand, as Roger Ascham noted as early as 1545: “For yf brasse, iron or style, have theyr owne strength and pith in them, they be farre above mannes strength: yf they be made meete for mannes strengthe, theyr pith is nothyng worth to shoote any shoote with all.”

Nevertheless, mentions can be found throughout the archery literature of experiments to produce working bows of various metals from the 17th to the 19th centuries, usually also detailing their shortcomings and failures.

This didn’t stop inventors from trying though, and Dave Egalton lists a surprisingly large numbers of patents being filed and granted, mainly in the US, from the 1870s onwards. Some of them contain clever details, others are outright ridiculous, but none of them seem to have gone into actual production – or at least no examples survived.

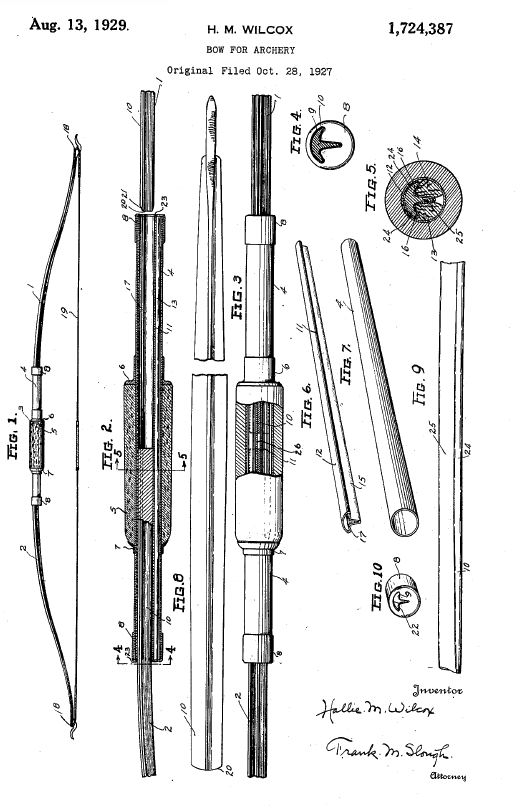

This only changed in 1927 with the design of one RH Cowdery of Geneva, Ohio, who used the stepped sections of swaged metal tubing from golf clubs for his limbs. Although his bows “habitually broke” (Egalton), this inventor was on the right track, and on 28 October 1927 he and one Hallie M Wilcox each individually applied for a revised design patent, both represented by the same attorney, and both in the name of The American Fork & Hoe Company. Sadly, the reasons for this historical oddity are lost in time.

The bow was a two-part take-down with limbs made from metal tubes pressed into a T-shape inserted into a round tube, which accommodated a simple cork grip. The lower limb was fixed, the upper simply inserted in the central tube, and no screws or pins were needed since the limbs were prevented from rotating by their shape, and from falling out by the tension of the string.

In the following years Cowdery kept filing for applications to improve on his original design, changing the limb profiles from T to U-shape, and introducing tapers in both overall diameter and thickness of the walls.

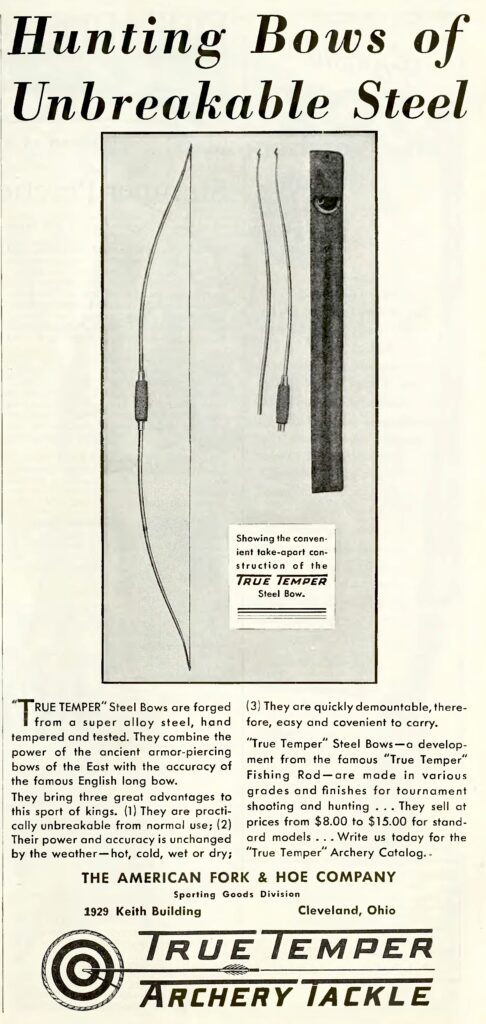

It seems it was only his latest design variation that finally went into mass production at The American Fork & Hoe Company Sporting Goods Division, and was marketed under the True Temper brand, which was also used for golf clubs and fishing rods and became the company’s official name in 1949.

A 1931 ad claims that: “TRUE TEMPER Steel Bows are forged from a super alloy steel, hand tempered and tested. They combine the power of the ancient armor-piercing bows of the East with the accuracy of the famous English long bow. They bring three great advantages to this sport of kings. (1) They are practically unbreakable from normal use; (2) Their power and accuracy is unchanged by the weather – hot, cold, wet or dry; (3) They are quickly demountable, therefore, easy and convenient to carry.”

When exactly the bows went out of production could not be determined. The company still exists as a manufacturer of gardening tools, but they are either unable or unwilling to answer questions about their archery history. Today, True Temper steel bows are occasionally offered online or at auctions, but they are a rather rare find, particularly if in good condition.

When Cowdery was granted his first patents, one Nils J Gille became the new head of the company See Fabrik Aktiebolag in Sandviken, Sweden, a manufacturer mainly of metal tubing for the bicycle, aircraft, and other industries. Gille was very interested in sports, and according to some sources was inspired to produce archery bows from his company’s materials during a visit to England.

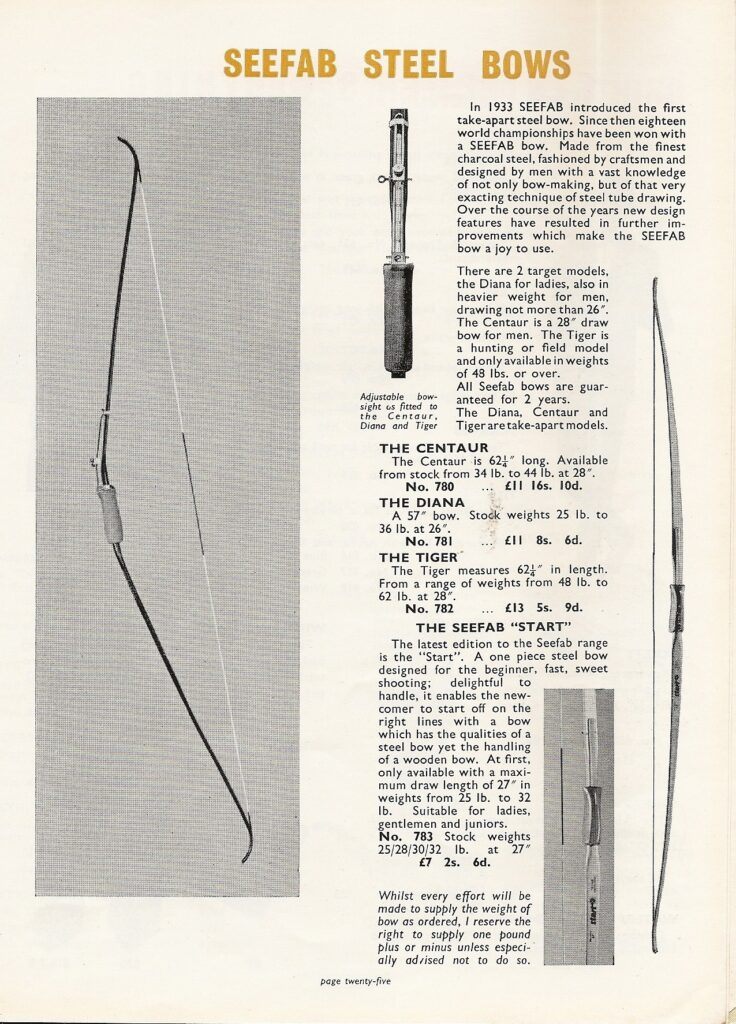

An engineer named Eric Hansson was involved in the design process, and commercial production began in 1933. Subsequently Gille and Hansson applied for, and were granted, several patents in the UK and the US, and SEEFAB bows were marketed worldwide. They were similar to the True Temper bows in having a cork grip and removable upper limb, but were made from flattened tubes of cold-drawn carbon steel.

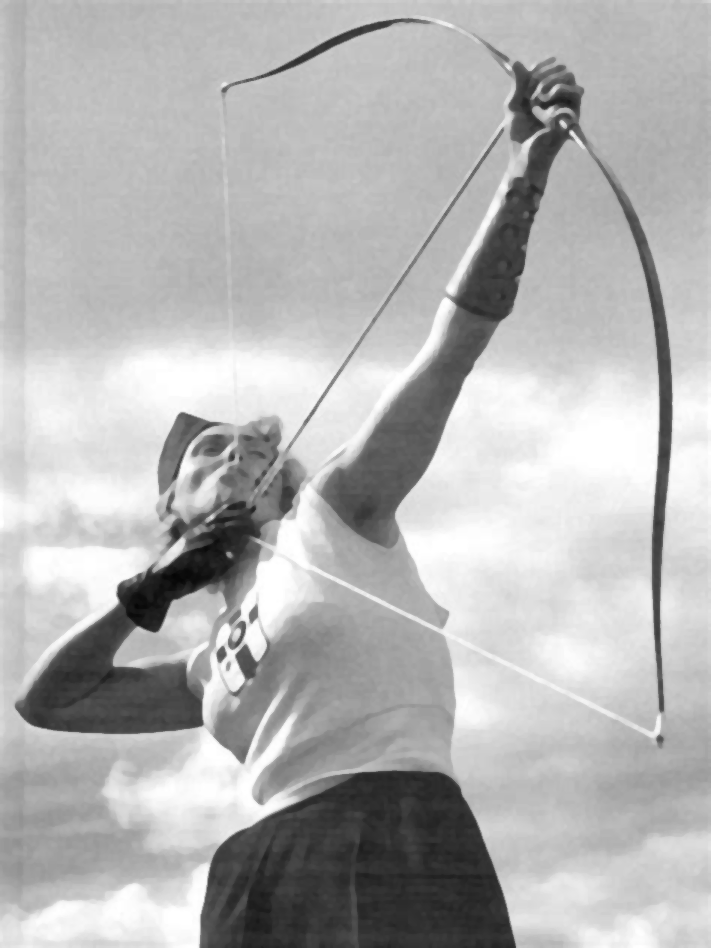

Early models were rather heavy and slow, but by the mid-1940s their performance matched or surpassed that of more conventional contemporary bows. Three models were available, the ‘Diana (for the ladies)’ of 57in in length, ranging in draw-weight from 25 to 34lb at 25in; the ‘Centaur (for the men)’, 62¼in long with draw-weights of 34 to 44lb at 28in; and the 62¼in ‘Tiger (for the hunters)’ with 45 to 63lb.

The SEEFAB steel bows became very successful in short time, and in the mid-1950s the See Fabrik Sportsmanufaktur Avdelning produced 3,000 bows, and 30,000 steel arrows (along with 15,000 pairs of ski poles) per year. Magazine ads of the time claimed that “More WORLD’S CHAMPIONSHIPS have been won with SEEFAB BOWS than with any other.” [sic] Among those endorsing the SEEFAB bows was Henry Kjellson, the Swedish world archery champion of 1934 and president of FITA from 1949 to 1957.

An article by JCA Bowdler called “A Visit to SEEFAB” in the December 1950 issue of The British Archer magazine details the manufacturing and testing processes. The limbs were cold-drawn from chrome nickel steel, then tapered and flattened, with the degree of flattening determining the draw weight. One out of every 50 bows was subjected to mechanical testing by a machine performing 200,000 full draws.

During World War II, archery was pretty much put on hold throughout Europe, and one would assume that companies producing metal tubes were called upon to help produce more serious weaponry.

According to some sources though, one such company, Accles & Pollock Ltd of Oldbury, Birmingham,

was approached by the UK Government to develop a demountable steel bow for use as a stealth weapon for commando operations by Allied forces.

Although nothing came of this idea, if it was even ever seriously considered, Accles & Pollock started designing such a bow shortly after the end of the war. It was very similar to the SEEFAB models, but cold-drawn from chrome molybdenum steel and subjected to a process called ‘shot-peening’, which meant bombarding it with shot fired at it under pressure.

As a result, the bow in its braced state was under compressive stress, which the material could easily stand without fatigue. During the draw the limbs then passed through the neutral position before tensile stress started to build up, so that at full draw the stress level was much lower than it would normally be, without loss in draw-weight. According to the manufacturer, this treatment gave their steel bows “10 times the fatigue life that could normally be expected”.

The official launch of the Apollo bows – a nod to the company’s name, and to the Greek god of archery – happened at a meeting between the Grand National Archery Society (GNAS) and representatives of the British archery equipment industry in 1946.

Accles & Pollock began to produce a variety of models, all named after birds, in two categories: the 66in Falcon (37–46lb), the 60in Kestrel (30–43lb) and the 58in Merlin (24–37lb) in the Championship range; and the 64in Martin (34–40lb), 62in Kingfisher (34–40lb), 58in Swift (24–30lb) and 56in Swallow (22–27lb) in the Clubman range, each one in a unique colour. The dark green Condor came in 64in or 66in length with 50–65lb draw weight and was meant for bow hunting, which was still legal in the UK at that point.

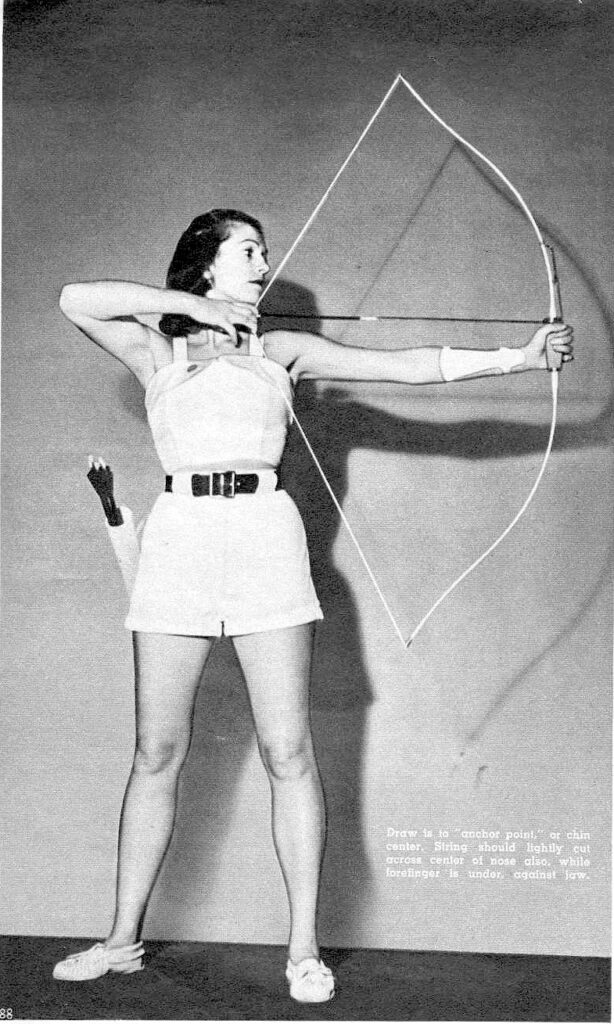

Like in the True Temper and SEEFAB models, the upper limb could be removed and was held in place without pins or screws. The Mark I models were rather simple, and it was only with the Mark II versions that an arrow shelf was introduced, which included a simple visual draw check in the form of a small band of rubber protruding up from each side in front of the arrow. A bow-sight in chromium plated or gunmetal bronze finish became available for all models, which could be attached to the front of the upper limb.

The engineering and marketing divisions at Accles & Pollock were probably aware of SEEFAB’s claims concerning their rigorous quality testing. At any rate, they made it known to the world that their limbs were checked by bending them 15% past their regular maximum for six repetitions,, and one in every 50 bows was machine-tested with 250,000 full draws.

Breakage in use appears to have been rare indeed, but the guarantee card nevertheless recommended wearing a cap with a rubber peak for protection. It also suggested pouring oil inside the tubes after use, a measure that was apparently widely neglected, which may account for some breakages and the poor state of some surviving examples.

Like the True Temper and the SEEFAB bows, the Apollo Mark I originally came with a thin metal string, which was later substituted by linen or Fortisan, a synthetic yarn used in parachutes, with very small loops because of the particular shape of the nocks.

Accles & Pollock also offered two ranges of metal arrows of various lengths to match their bows, the Championship arrows made from aluminium alloy tubing, the Clubman variety drawn from high-tensile steel, all equipped with plastic nocks and 3in shield fletchings.

In the 1950s a company in Wolverhampton named P&S Designs produced three models of bows made from aluminium alloy; the Regent, the Princess and the Consort. They were advertised and sold in Britain, but it is unclear if they were also exported to the US or the Continent, and don’t appear to have been on the market for long.

August Stukenbrok, a German company from Einbeck that started as a bicycle manufacturer but later diversified into firearms and other hardware goods, offered a steel bow as early as 1913. The Chic model was made from layers of flat spring steel, operating on the principle of a leaf spring, and was advertised as shooting up to 70m. It doesn’t appear to have been a great success though, since no further information, let alone surviving examples, could be found.

The most successful steel bows both commercially and in competitions were the SEEFAB and the Apollo models. Of the 53 male archers participating in the 1957 World Championships, nine used SEEFAB and eight shot Apollo bows, out of a total of 17 different manufacturers. Ten of the 34 ladies preferred Apollo and five SEEFAB, with only eight other makers represented, according to a list in The British Archer (December 1957).

But the dominance of steel bows on the shooting lines didn’t last much longer, and the reason is already visible in this statistic: all the other bows were glass-backed recurves, which at that time became more and more efficient, cheaper, and offered better shooting comfort.

Producing efficient metal bows only became possible thanks to new materials, new machinery and new manufacturing processes. But within decades of their successful arrival they were already being replaced by even newer and better materials, machines and processes.

Yet while the technological evolution never ceases, the time-tested wooden self or laminated bows still hold their ground, and composite bows are even making a comeback. Wood lasts longer than steel it seems – at least in traditional archery.