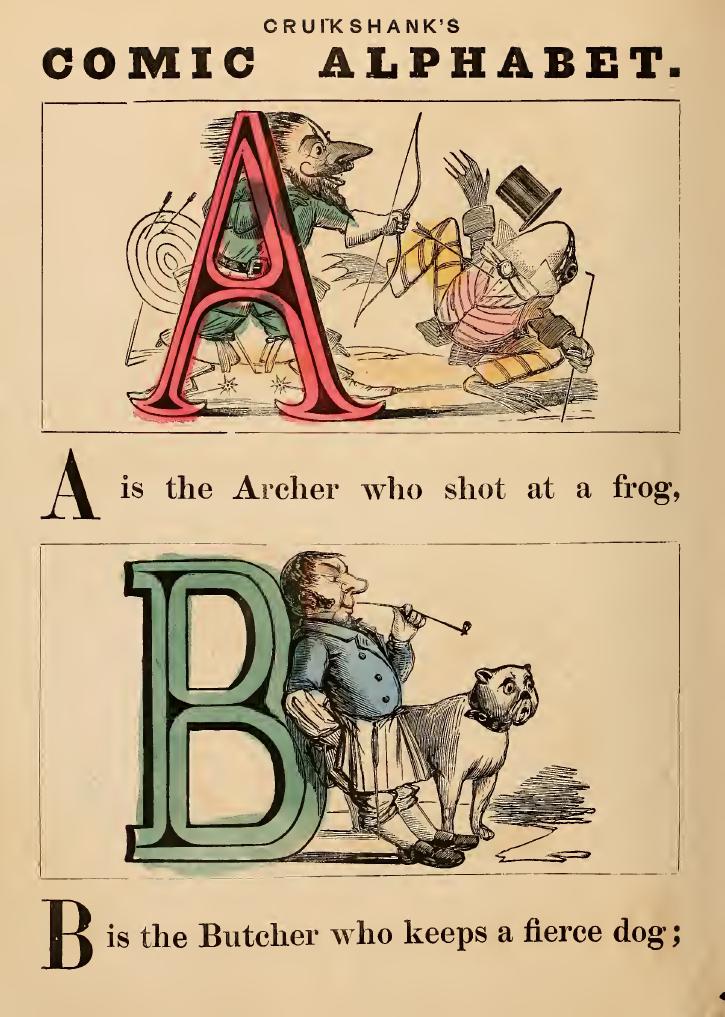

Kristina Dolgilevica takes another look at the archery revival in 18th century England

The history of the 18th century is often dismissed by the modern reader as uninteresting, lacking the mystery of ancient history and the curiosity of medieval history. Others are put off by the perceived, sometimes over-simplified class divisions of the nobility, gentry and the poor.

Every age has its injustices, however, and if you are an archer or have any interest in the sport, it is worth your attention to give this age a second chance; the health and popularity of our sport today springs from a few seeds planted during the second half of the 18th century.

It was a period of significant change, when secular literature and scientific discovery flourished – the European Enlightenment – but also a time when people looked back with fascination to the past and became interested in reviving old customs and pursuits, including the use of the bow. Here, I will attempt to summarise the historical context to the 18th-century archery revival efforts, highlighting some notable figures, events and works, and I hope this will spark some curiosity in the reader.

The Archery Revival Timeline

During the course of the 15th and 16th centuries, archery still had real military significance. However, it was already on the decline. The first book on archery technique and practice, Roger Ascham’s Toxophilus, published in 1545, was dedicated to Henry VIII, who was himself an avid promoter and exponent of archery.

By the second half of the 17th century, however, the bow and arrow had fallen out of martial use due to the advances in firearms and was consigned to competition shooting as a pastime. Archery societies begin to spring up across the country, particularly in the north of England and Scotland. Most notable of those was London’s Society of the Finsbury Archers, which was founded in 1652 by Sir William Wood.

The subsequent revivals of the 18th and 19th centuries were very different in nature. The latter was part of the much more general expansion in the popularity of all sports. On the other hand, many of the major archery societies of the 18th-century revival were short-lived, with most formed around 1770 and lasting a couple of decades at best before they declined into insignificance or disappeared altogether.

A few clung on, laying the foundation for the renewal of interest that began in the reign of George IV and blossomed under Victoria, supported by the emergence and growth of a new wealthy middle class with time and income to spare. They were imbued with a greater sense of self-worth, especially after the electoral reforms of the Reform Act 1832.

The Age of The Club

To what do we owe that brief but important surge of interest of the 1770s? First of all, there was this new spirit of enquiry that manifested in scientific, philosophical, literary and antiquarian discussion and research, of particular significance for the sport of archery and the growth of the club.

It was an age of clubs, from the fashionable clubs for the very wealthy, where the principal occupations were eating, drinking, conversing, gaming and gambling, to the more modest occupations of coffee houses.

Being a member of multiple clubs was commonplace, and being a member of multiple archery societies was not unusual. But there were also many clubs where the principal occupation was intellectual argument, where gambling and excessive consumption were eschewed.

The most famous example would be The Club, founded by Joshua Reynolds the portrait painter. It included Samuel Johnson the lexicographer, Edmund Burke the politician and essayist, David Garrick, actor, and Oliver Goldsmith, poet.

In clubs of this intellectual sort, two of the requirements of the fashionable clubs – having vast wealth and being a man – no longer applied. Here it was possible to encounter both struggling actors and merely educated thinkers, male or female, often from modest backgrounds.

The second half of the century was the age of the bluestocking, when opinionated or educated women became accepted into intellectual society.

The ethos of the club extended into the sporting world as well, in an era when the predominant sports were horse racing and cricket. The Jockey Club was founded in 1750, and the establishment in cricket of formalised clubs such as Hambledon also came in the second half of the century.

But these were exclusively male preserves, whereas the archery societies which grew up a couple of decades later were quite different in composition and nature. Within individual archery societies the make-up of the membership could be family-oriented, or indeed the opposite. Thus the membership list for the Royal British Bowmen in north Wales shows 101 members, 24 of whom are individuals and 77 were members of a family group, with the ratio of men to women being 55 to 46.

At the other end of the spectrum, the Society of Royal Kentish Bowmen at Dartford had no female members, but instead a rule that jocularly imposed celibacy on its members and included a fine on any member who married.

This disparity demonstrates that societies could have different social functions, and casts doubt on the validity that the sport of that period as a unified movement. The inference is that some of the societies had more in common with the intellectual clubs, their focus more on enjoying social intercourse than on the sport itself. But there is more than a connection of purpose between the two.

The Age of Antiquarianism

This was also the age of antiquarianism, a blossoming of curiosity about the origins and history of peoples and places. In literature, antiquarianism and medievalism were ascendant: there were poems founded on antiquity, such as MacPherson’s Fingal, and a plethora of antiquarian topographical studies by authors such as Richard Gough and Francis Grose.

Such works were an important subject of discussion, and their authors were active members of the clubs. The revival of interest in the longbow, and the part it had played in the nation’s military history, was a part of this movement, a connection emphasized by the importance in the conduct of the societies of a degree of pageantry and ritual, and their strict rules about the wearing of the club uniform.

Thus, it was no accident that the seminal work on the construction and use of the longbow, Roger Ascham’s Toxophilus, was republished in 1761 as part of his complete works in English. This kinship between the clubs and the archery societies is underlined by the multiple memberships of individuals, not only between different societies, but between societies and clubs, especially in London and the south-east.

Alongside these cultural influences, the 18th century was a period of industrialisation and commerce, fostering the growth of the merchant class whose wealth could compete with that of the landed gentry; people like Henry Thrale, whose brewery was sold to David Barclay on his death in 1781 for the equivalent of £13.5 million in today’s terms. Thrale, like others of his class, mixed with the gentry and nobility. Such individuals, well able to afford the subscriptions, also joined the archery societies.

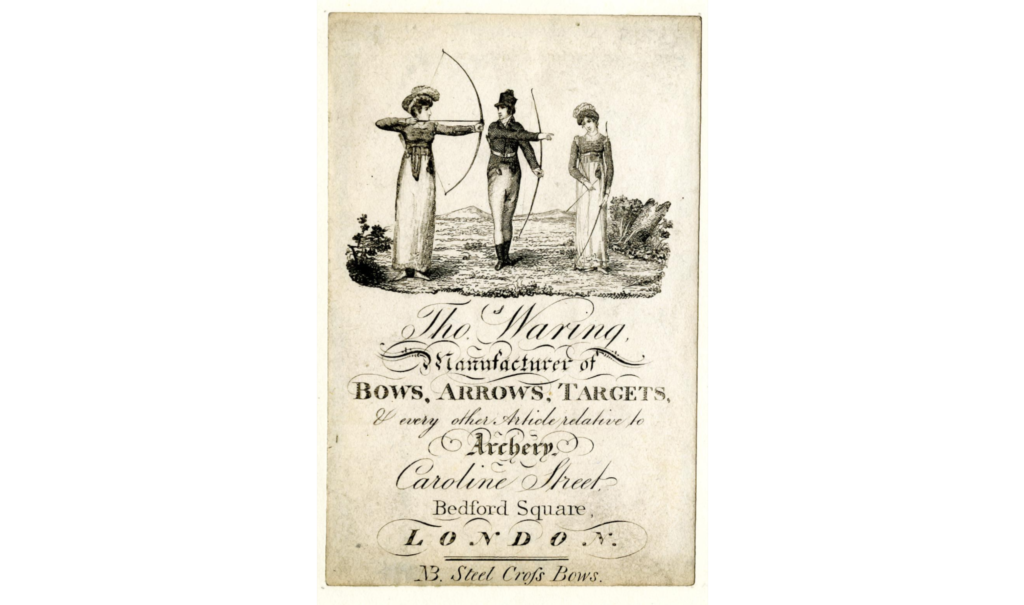

But archery remained a minority sport, its fortunes governed by a few dedicated individuals. The two credited with igniting the archery revival are Sir Ashton Lever (1729 to 1788) of Alkrington Hall in Lancashire, and Thomas Waring (1730 to 1805).

Sir Ashton Lever

Lever had been involved in horse racing as a steward at Manchester racecourse in the 1760s, was a dedicated huntsman and a member of the Broughton Archers in Manchester. This was an exclusive society, limited to 20 members, and one of the oldest in the country, having been in existence at least since the 1660s.

He was a collector of natural antiquities and curiosities. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1773, and the following year he moved to Leicester House in London, on the site of the present Leicester Square, near the residence of Reynolds, and opened his Holophusikon, a museum exhibiting the collection he had amassed at Alkrington.

He had founded the Middleton Archers, in Manchester, in 1777, as well as the Archers’ Hall in Regent’s Park for the Honourable Artillery Company. In 1781, he and Waring established the Toxophilite Society in the Leicester House residence, with some members as eminent as the Duke of Norfolk and Duke of Leeds.

Waring had studied bow-making with Kelsal’s of Manchester, one of the most prestigious makers in the country, and after the establishment of the society he ran a business supplying bows and archery equipment, initially from Leicester House and later from business addresses in the Bloomsbury area. On 15 July 1786 he also joined the Kentish Bowmen.

The Toxophilite Society, which exists today as an exclusive society accepting members by invitation only, formed the model for other archery societies that sprang up in the 1780s and early 1790s. It was the first society to secure the patronage of the Prince of Wales in 1787, followed by the Royal Kentish Bowmen (established 1785, royal patronage 1789) and the Royal British Bowmen at Wrexham (established 1787, royal patronage 1789).

Despite his best efforts, Lever’s museum was not a financial success and he was forced to dispose of it by lottery in 1786, after which he returned to his ancestral home where he died only two years later.

The decline in Lever’s fortunes and the shortness of his life match the transience of the movement he fostered; most of the archery societies that followed his own over the succeeding few years sadly foundered during the 1790s.

A Minority Sport

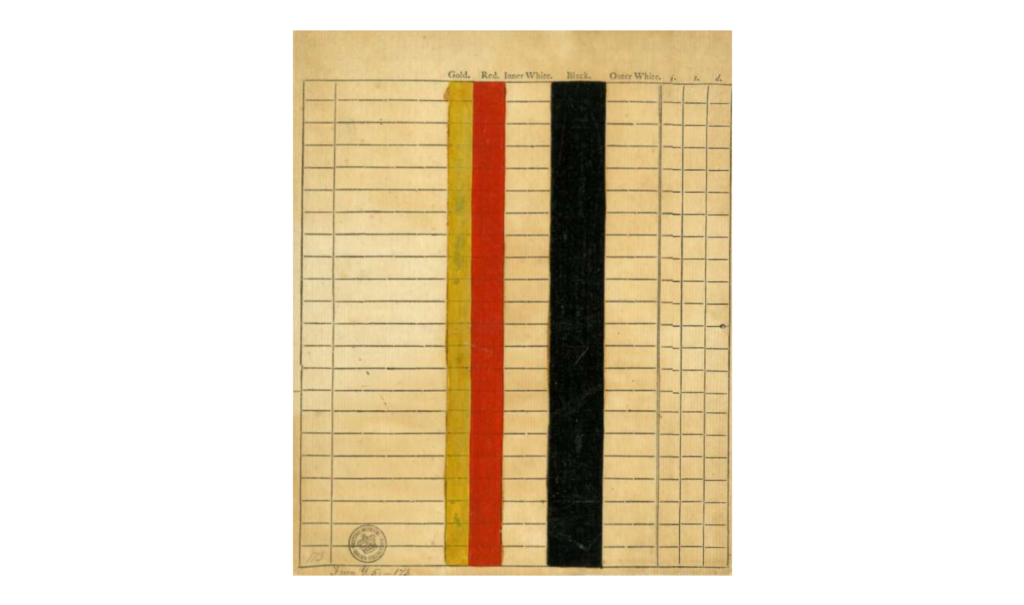

References to the operation of the societies are rare; such information is gleaned largely from the surviving rule books. From these, it appears that there was no standardised organisation or indeed function; shooting arrows was not necessarily a society’s main purpose. Some societies, especially smaller ones with members of modest rank, may have been almost wholly dedicated to the sport, while others may have used the sport as an excuse for lavish dining.

But all would have offered the opportunity for discourse and what is now called ‘networking’. However, memberships rarely exceeded 120, including individuals who belonged to more than one society. So, it should be emphasized that archery was definitely a minority sport, probably involving at the height of its popularity no more than 2,000 people – a tiny proportion of the population, even of the gentry. Generalisations are impossible.

Why was the 18th-century revival so short-lived? It is tempting to attribute it to the massive social changes underway in society during the 1790s. The established class system was beginning to be undermined by the effects of the Industrial Revolution and the consciousness of the French Revolution, though the stable structure of society and the equanimity with which it was perceived by all classes remained largely unmoved during most of that decade. Nevertheless, commercialism had little tolerance of such nostalgia.

But perhaps the more significant causes were inherent in the sport itself. Firstly, archery was hardly a spectator sport, like horse racing or cricket. For safety, the onlookers had to be – or were supposed to be – positioned behind the archers, and the archers themselves, shooting at anything up to 100 yards or more, were often unable to see where their arrows had struck.

Secondly, archery did not have a true centre, as cricket did at Lord’s Cricket Ground in London (from 1787), or horse racing at Newmarket. From the surviving rule books we can only infer the existence of a few well-attended societies clustered together in the south-east and north-west, and a scattering of small and probably ephemeral ones in-between.

The separation of its two main centres, despite the improvement in the road system, road construction and carriages after about 1780, was not conducive to intercourse between the two and thus to the durability of the sport.

Thirdly, though both archery and cricket were seasonal, (the archery season was usually April or May to September or October, roughly six months), and generally dormant through the winter, cricket’s popular following was encouraged by the ability of followers to get together and have an ad hoc game among themselves with a ball and some makeshift bats.

Perhaps the easiest explanation for the decline is the sport’s inherent weakness at this period, having too narrow and too dispersed a member base to sustain its existence. Nevertheless, the 18th-century revival served a vital purpose: to supply a model which allowed the sport, with its wider foundations, to become quickly established and consolidated during the 19th century and thus go on to form the basis of modern archery.