Bow International have compiled a list of some of the essentials for your collection – and why. By Tom Hall, Emma Davis and Bow Staff.

Archery

Author: USA Archery

Publisher: Human Kinetics Publishers, 2013

The official handbook from USA Archery, this book sets out to provide a comprehensive guide to all areas of shooting recurve and compound. As a reference book it contains a wealth of information, with chapters covering aspects of equipment set up and tuning, training methods and planning, technique and mental strategies.

Topics are divided up into self-contained chapters, with contributions by KiSik Lee, Guy Krueger and Butch Johnson, among other well-known names.

A large bulk of the book is dedicated to recurve shooting technique in the form of the KiSik Lee NTS method, with a thorough explanation of why this method has been chosen.

This is the standard approach to shooting that is taught in USA and it has a lot going for it, as evidenced by the success of USA archers such as Brady Ellison – who provides a effusive foreword recommending the book to anyone and everyone.

However, the full NTS method as written requires high levels of physical strength and endurance and there are arguably more bio-mechanically efficient techniques, such as the Korean method. In particular, the NTS method is favoured more markedly by the USA men’s team, while the USA women’s team exhibits more variety in approach.

The chapter on making practice more effective is also to be taken with a pinch of salt; a beginner sample training plan involves shooting upwards of 1,000 arrows a week across five training sessions and the intermediate training plan looks closer to a full-time job! There’s some good theory in here about periodising your training, but don’t feel you need to add everything in at once.

“My copy of this book is well-worn, and for good reason. A great reference book for archers of all levels.” – Emma

Some of the most interesting sections are those that are potentially most likely to be overlooked. The first chapter, if you filter through the factual information specific to the structure of USA Archery, sees Butch Johnson take the reader on a philosophical exploration of what it means to be a competitive archer.

There are simple concepts here that the majority of us could benefit from thinking about, such as the quality of our training environment or the purpose of our goals.

Similarly, it would be easy to skip past the chapter on nutrition and physical training, but the section on shoulder strength training is vital for injury prevention. The chapter on preparing and peaking for competition also makes an interesting theoretical read that should prompt some deeper thinking about how you plan your season.

For those still learning their shooting technique (which is 99.9% of us!) this is a great resource to try things from and use to explore a particular shooting style. Most archers, coaches or parents would benefit from reading this book, and then by keeping it as a point of reference to inform (but not dictate) their onward journey.

Bullseye Mind

Author: Raymond Prior

Publisher: Momentum Media Sports Publishing, 2016

This is a rather slim book, which perhaps might give the illusion that the contents are light or limited, but this is very much not true. Designed as a short guide on psychology for rifle shooting, Bullseye Mind targets the most commonly made mental errors and gives detailed guidance on how to combat them.

The similarities between rifle shooting and archery as sports allows for straightforward transposition into a frame of reference appropriate for our sport and all the key principles ring true.

The book is divided into many short, dense chapters, each presenting a specific common flaw in mental preparation or routine, rationalising how this can hinder the achievement of consistent performance and presenting a simple method on how to think differently.

Topics include the dangers of not having a consistent pre-shot routine, the common mistake of over-engaging the ego, how to deal with fear and anger whilst competing, and a lovely section on not putting limits on your dreams – it’s okay to dream big so long as you have an action plan.

This problem/solution format is very easy to digest and makes it possible to pick up the book and immediately select an area to focus on that feels particularly relevant to you – a massive benefit for those that struggle to keep focus from cover to cover.

Crucially, pretty much everything in here can be applied straight away, and the principles outlined are evidence-based and logical in their presentation.

Each chapter is centred around an anonymised case study based on athletes that the author has specifically worked with, used as examples to provide context and make the ideas presented more relatable.

“One of the most important books I’ve read, I absolutely recommend this to everyone.” – Tom

This works very well, providing the reader with more guidance on how to identify similar problems within their own mental performance.

The end of chapter contributions also provide an insight into the elite level performance mindset, with contributors including multiple Olympic medallists, national coaches, world champions and even a team leader from the US Marine Corps!

Despite all of these positive elements, don’t expect any quick fixes. The author, who has a PhD in Sports and Exercise Psychology and has worked with Olympic champions, is careful to stress that he is not a magician.

You will not find any short-term tips or tricks in this book, but instead a guide on how to build mental toughness over time through practice and persistence using “good information and common sense”. The goal is a sustainable mindset that requires commitment and continued effort to build.

Evidently, from the wealth of success experienced by the various contributors to this book, these methods can be a powerful tool. So long as you don’t expect it to change your shooting overnight then there’s no telling where it could take you.

The Inner Game of Tennis

Author: W. Timothy Gallwey

Publisher: Pan, first published 1972

Although a fairly short read, at only 134 pages, the philosophy outlined in this book really gives pause for thought. Amongst a litany of books claiming to deliver the secret formula to becoming a winner, Timothy Gallwey encouraging us to think about why we compete and what winning should actually mean remains a breath of fresh air.

Written and published in the 1970’s, when sports psychology was still fairly new, Gallwey’s theories were revolutionary at the time.

The first half of the book is dedicated to a concept that is now well established: the distinction between the conscious and subconscious self, rooted in the simple idea that the conscious has a tendency to interfere with the abilities and performance of the subconscious.

If you’ve read any of the more recent popular science books on psychology (The Chimp Paradox, Thinking Fast and Slow) then this idea won’t be new. However, the way it’s presented here feels different.

Greater thought is given to how this relationship between the conscious and the subconscious affects how we learn, with some wonderful insights that emphasize the detriment of over-coaching – detailed explanations of what students “should” be doing prompt over-engagement of the conscious mind.

The ideas about using exploratory learning, where you encourage students to discover the best technique themselves, provide a zen approach to mastery of skill that feels incredibly intuitive.

The section on games people play within themselves is likely to ring true for a lot of archers, particularly the discussion of common traps such as the relentless perfection of form, defining one’s self worth by winning or losing, or getting caught up in how your performance affects how you’re perceived by your peers. This mental game analysis leads neatly into a discussion on competition: why do we compete and who are we really competing with?

”Some really eye-opening ideas about how we learn: a must for any coach!” – Emma

As Gallwey says: “If I assume that I am making myself more worthy of respect by winning, then I must believe that by defeating someone, I am making him less worthy of respect.”

This is an uncomfortable perspective that exposes some inherent problems in how we might perceive victory but prompts a rich exploration of what it truly means to win.

The theory here may have the potential to improve performance dramatically, but the true message is rooted in the thrill of the challenge and discovering the depth of our own capabilities.

As the title suggests, the book is about improving your tennis game, although much of it is actually more applicable to precision sports like archery that it would be to tennis.

Some of the cultural references have dated and a number of the points are anecdotal, but there is something beautifully elegant about Gallwey’s theory. In letting go of our conscious desires for success and recognition, we could perhaps uncover the pure joy of performance without judgement.

The Art of Repetition

Author: Simon Needham

Publisher: The Crowood Press, 2006

In the opening lines of his first book Simon wonders what he might have achieved had he known at the beginning of his archery career what he knew by the end of it.

The Art of Repetition is a result of his attempt to distil the learnings of a 20-year journey.

This book shows its age, in the monochrome photos and homemade illustrations, but also as a result of the extreme level of detail Needham goes into on such diverse topics as entering competitions, arrow plotting and string building.

Unfortunately, many of the specific references in these sections are now obsolete.

Assuming zero prior knowledge, we begin with Needham’s take on basic shooting technique and a guide to buying your first set of equipment. The information presented is solid but very prescriptive, and it does seem likely that those coming across this book will have already completed a beginners’ course covering the majority of this content.

Equipment is a strong theme in several detailed follow-up chapters, and in particular Needham’s guide to setting up a bow provides excellent step-by-step instructions.

However, he also provides plenty of detail on the how and the why: for example, he takes the time to illustrate exactly how the tiller bolts change the limb pocket angle and as a result the bow poundage. This is invaluable to the archer who wants to understand, rather than regurgitate, these methods.

“For me this was dead useful in my early years of shooting. It’s old but thorough and should set anyone fairly new to the sport well on the way to being an independent archer.” – Tom

Some of the chapters which serve as introductions to other broader areas of sports performance aren’t as strong. The discussion on psychology starts well: discussing the role of the conscious mind in skill execution, but soon diverts into an almost encyclopaedic explanation of Neurolinguistic Programming (NLP) and learning style preference theories that are still not fully proven to be effective today.

The chapter on fitness is also flawed, containing such instructions as to focus gym programs only on “light weights and high numbers of repetitions”.

This may have been the prevailing wisdom at the time but is strongly contradicted by the practices of current elite archers. However, it is at least nice to see the importance of exercise, rest and nutrition being emphasised, as these aspects often get passed over!

Overall then, The Art of Repetition is perhaps best considered an unusual reference text, although the book remains in print and is a familiar sight on the not-well-stocked archery section in larger bookstores.

Needham’s DIY attitude and clear guidance on aspects of equipment may well provide the inspiration needed to overcome a nagging issue. Although not a riveting page-turner, there is a lot to be learned here for the beginner to intermediate archer.

Ultimately, very few books manage to achieve the golden trinity of affordability, quality, and breadth, and Needham has managed a reasonable compromise on all three.

With Winning in Mind

Author: Lanny Bassham

Publisher: Mental Management Systems, first published 1988

With Winning in Mind is a manual for the Mental Management System developed by Lanny Bassham, who used it to great effect for a number of years whilst dominating the international world of rifle shooting, including winning Olympic gold in 1976.

In shooting sports and golf, the resulting philosophy and mental training techniques have generally been positively received, and it is a popular book amongst serious archers – but we believe it deserves a particularly thorough discussion because it is definitely not a method that will suit everyone.

Early on in the book Lanny lays out key principles, making the methods clear and easy to follow. However, the aggressive ‘my way or the highway’ approach implies this method is the only one worth considering.

When introducing the Mental Management System, he goes as far as to suggest his principles “govern how the mind works” with as much certainty as the laws of gravity.

He also claims explicitly that these principles “work for all people, all the time,” seemingly expecting his work with highly successful sporting individuals to stand as anecdotal evidence.

The Bassham method is particularly dominant in American recurve archery. Brady Ellison, USA Archery team shooter and three-time Olympian, is one of the higher profile advocates of the system within our sport.

In an interview in the run up to the 2012 Olympics, where he won a silver team medal, Ellison said: “I work religiously on my mental game. I think that alone makes me stronger than anyone else.”

Here Ellison is affirming, publicly, that he is “stronger than anyone else.” This level of confidence and self-belief, particularly when dealing in absolutes, is central to the With Winning In Mind philosophy.

The section on positive affirmations reflects the importance of a belief so strong that it is basically faith. A positive affirmation is a statement where you take something you want to be true (e.g. a goal to be national champion) and write it as though it has already happened: “I am a national champion.”

The basic theory is that you then read this affirmation daily until it comes true. Lanny boldly claims that one of two things will happen: you will stop repeating it or it will come true.

The perceived positive impact of this is mainly because if you repeat something enough times you will begin to believe it. Believing you have already achieved a goal can take some pressure off; if you’ve already done it then doing it again is easy, right?

“This was the first book on sports psychology that I ever read and it opened my mind, the ideas stuck even if most of the methods did not.” – Emma

If your self-image is strong then it is easier to allow your subconscious to take over, leading to better results. By the time Lanny got to the Olympics in 1976 he had already won the gold medal hundreds of times in his mind.

However, this argument isn’t without flaws. Imagine a scenario: you have spent the previous 12 months affirming daily that you are the winner of XYZ championships, but on the day an early-round opponent shoots an astonishing match and knocks you out.

Can you detach yourself and restart the process? How many times can you maintain 100% certainty that you will win without actually winning? This method can be used to great effect, especially if you are at, or close to, the pinnacle of your chosen sport and win fairly regularly, but an underdog may find the methods less beneficial.

The idea of building a mental program is a concept frequently used in archery. As a key element of our sport is being able to find consistency between shots, it makes sense that we should aim for consistency in our thoughts.

The concept here is reasonably sound, but the execution is once again rigid, splitting the program up into defined chunks. However, this style of guidance may be good for the archer who wants an off-the-shelf routine they can implement straight away, and Lanny does encourage personal reflection on the content.

While a lot of the theories behind this book do have scientific basis, the specific methods outlined are mostly based on anecdotal evidence. The Mental Management System and its strict rules appear to have worked very well for a number of international athletes, including Ellison, but it is impossible to say how reduced their achievements would have been otherwise.

It is also important to consider whether the same methods will make sense for World Champions, emerging athletes and club archers. It seems unlikely.

The key message here is that reading one sports psychology book does not a consistent winning mindset make, even if you learn every word by heart. This book is a valuable contribution to shooting psychology; by all means read it, discuss it, use it, but make sure it’s not the only book you read.

Research around the topic and find a method that works for you, not just for famous faces. It’s possible that this system is a perfect fit, but it’s worth taking time to try different approaches and see what feels right.

Tom Hall says:

As one of the first shooting-sport-specific psychology books I read, I was initially very excited to apply the methods within. We bought the audio book at The Vegas Shoot in 2017 and it has prompted many discussions over the years.

Lanny’s voice is very relaxing, and it’s a great way to absorb the information slowly. However, as I’ve grown my own understanding of the methods I use for performance, I find myself starting to disagree with some of the core principles.

In particular, I find that while thinking and talking positively about upcoming events is important, affirmations often feel forced. For example, in the build-up to a national selection shoot I may talk, think and plan my season as though my selection is certain, but I would find it extremely jarring to say “I have won the selection shoot” as though the event had already happened. As a result, I often stopped reading this affirmation format and eventually stopped writing them altogether.

The WWIM method also strongly relies on protecting the self-image and focusing only on your successes. However, I also want to look back at and analyse any failed attempt at a goal, in order to maximise what I can learn from the experience.

Indeed, I will often attempt to perform this analysis in advance by deliberately using smaller events as trial runs or by a “pre-mortem” thought experiment.

I believe that by accepting the chance of failure I can achieve the same inner confidence as Lanny aims to achieve, but in a more stable manner. After all, I know I have done everything I can to prepare myself.

Archery Anatomy

Author: Ray Axford. Paperback, 164 pages

Publisher: Souvenir Press

Archery Anatomy is what it says on the tin: an introduction to anatomy aimed at archers (and coaches).

It’s pitched as a reference guide rather than an authoritative manual for archery technique.

Does it succeed? To an extent. The first stumbling block is the structure and flow of the writing itself. Sections within each chapter get a generic title with numbered extensions.

Likewise, the diagrams are all numbered but lack useful descriptive captions and many of them also look very similar at first glance.

This is partially forgivable as they are trying to depict small changes to true scale, but it clearly signposted differences would make for much easier reading. These issues make attempting to skim for information difficult, requiring you to plough through the bulk text to hunt down the key messages.

This isn’t any easier either, as the text contains many long sentences, with some making up entire paragraphs. Ultimately this makes Archery Anatomy challenging both as a read and as a reference book.

Moving on to the content, there is certainly some useful material. We start with a nice simple introduction to bones, joints and muscles with lots of clear diagrams.

The shoulder and arms naturally get the most detailed description, and a basic understanding this area is certainly useful to any archer who has found themselves nodding through a physio explanation of an injury. However, there are some confusing variations from modern terminology e.g. “great terete” instead of the “teres major” muscle.

The meat of the book starts in the second half with a solid discussion of forces about the bow shoulder. Axford emphasises considering both the draw force and mass of the bow. If angled correctly, the line of the resulting combined force can help prevent the bow shoulder collapsing backwards.

“I found this interesting as an intermediate archer, thirsty for knowledge. Coming back a few years later I realise this could be as confusing as it is informative.” – Tom

This is something new and intermediate archers often struggle with. Axford also shows how differences in body shape can make parts of this easier or harder, and explores the effects of changing the bow’s power to weight ratio. This section is definitely the highlight of the book.

The accompanying section covering the draw side is less clear. Mainly it focuses on different approaches to drawing the bow and comes out in favour of a ‘high draw’ over a ‘T draw’.

Yet many modern athletes are using the KSL angular draw to great effect. This variation alleviates many of the flaws of the T-draw, but is unfortunately too recent a development to be covered in this book.

In the end, Archery Anatomy is a bit of a mixed bag. On the one hand, there isn’t another book that fills the niche it occupies. On the other, it feels dated and is difficult to read.

It is something the more experienced reader should tackle if they get the chance – but, as Ray suggests himself at the end, be prepared to take a critical mindset, because there are no set answers when it comes to the human body.

The Pressure Principle

Author: Dr Dave Alred MBE. Paperback, 272 pages

Publisher: Penguin

“This book is dedicated to all those who think they can’t.”

These are powerful words for a powerful book – and the author certainly knows something about power.

Alred has worked with several athletes that require a combination of physical and mental power, including England rugby hero Jonny Wilkinson, whose quote adorns the cover of the latest edition.

Most examples in the book come from rugby or golf rather than target shooting sports, but the underlying messages are universal. Especially when it comes to spotlight moments, where it is just you versus the target.

Think of a match-winning penalty, a long putt to secure a championship, or the last arrow of a scored round. The feeling of pressure, that the whole world is watching and judging us, is one we can surely all relate to.

Covering a range of mental, social and technical factors, this book distills pressure management into eight simple principles. The result is a clear outline of the ways pressure can be anticipated and managed. He also references Timothy Gallwey’s The Inner Game of Tennis (reviewed in Bow 132) and reinforces a lot of similar ideas. Both authors encourage implicit learning in place of excessive explicit instruction.

Throughout, Alred’s principles appear well-founded and make logical sense. When covering technique, he asserts that you should aim to build a technique that will be robust in pressure situations. For example, he adjusts players kicking techniques to strike in a straighter line.

“There is far too much to learn from this book to cover in one reading, which is why I keep coming back to the principles within and applying them to my own shooting and life in general.” – Tom

The result is that increased muscle tension while under pressure creates less deviation. Discussing learning, he introduces the “ugly zone”, a place where you must fail repeatedly in order to progress beyond your present limits.

It sounds unpleasant but he urges us to learn how to make peace with being there. Advising on the power of language, he references the emotive words used in ad campaigns and film trailers. He highlights that non-verbal cues such as posture and body language are also shown to help with controlling performance anxiety.

While the book can be read cover to cover, each chapter mostly stands alone. Combined with the concise summaries provided at the end of each chapter, review and reinforcement is made easy. The finale is a brief motivational talk entitled “You Can Do This” and a short fictional story that displays correct use of the methods learned.

All in all, this is a well written book; easy to digest and with plenty of motivating examples throughout. His passion and belief in the power of effective language shines through in the writing itself. There’s a lot of overlap with similar works, but the focus on removing barriers through words and thoughts is what gives The Pressure Principle its magic touch.

Total Archery: Inside the Archer

Edition: 2019, 3rd Edition (first published 2009)

Author: KiSik Lee and Tyler Benner. Paperback, 3rd edition is 288 pages

Publisher: Astra Archery

Total Archery is a book we had known of for some time but had never considered buying. Perhaps largely because the only version we had seen was the hardcover 1st edition, which could fetch prices of over 200 pounds!

However, when this 3rd edition came out for a much more reasonable £45 it was clearly time to give it a go. The authors are KiSik Lee, head coach of the US Olympic Archery Training Program, and Tyler Benner, a US archer, coach and entrepreneur who trained with him for a number of years.

Firstly, we have to distinguish ‘Total Archery: Inside the Archer’ from its predecessor, ‘Total Archery’. Both are written by Lee, but the latter is a more general introduction to archery and is aimed at beginners. Inside the Archer is a more advanced book focused purely on shooting technique as taught by Coach Lee. This technique has become officially part of the USA national training system and is taught to coaches to pass on to new archers throughout the States.

Over the course of 28 chapters Inside the Archer drills down into the minute details of every aspect of shooting a bow, to create possibly the most detailed shot routine explanation ever.

The chapters tackle one element of the technique of shooting at a time, progressing approximately in the order they might be carried out. Stance and posture are tackled first, followed by gripping and hooking, then how to raise and draw the bow, anchoring and transferring, then finally expansion and follow through.

Each chapter mostly stands alone, although there are helpful cross references between them, and there is a vast depth of information to be covered in each. This is not a book you will be able to read cover to cover, instead it is better to take in one or two chapters at a time and then spend a while putting these things into practice.

Whilst there is a lot of text, one of the real strengths of this book is the number and quality of the diagrams. (This third edition of the book states that there has been a “contemporary design and reworking of diagrams and figures, to make the most salient points jump off the page while retaining the original text.”)

Comparison is regularly used to demonstrate differences between correct and sub-optimal aspects of shooting technique. Photographs which display very subtle differences in form are strategically overlaid with markings to make them easy to understand. Newer coaches especially will find this invaluable in learning how to assess and correct technique from visual cues.

In the foreword, Lee recommends reading the book three times: once in detail, once focusing just on the pictures and a final time absorbing the Key Points summaries, which can be found at the end of each chapter. In reality, the volume of information here means that even after three read-throughs there will still be much more left to learn from this book.

The diagrams and technique descriptions, and justifications, are likely to prove valuable and thought-provoking across an entire career, even for the more experienced archer or coach.

The main limitation, as is often found of any technique-focused book, is the absolute commitment to one specific style of shooting. KiSik Lee’s method has been used to great effect – most notably in recent years by Brady Ellison, who indisputably dominated the outdoor circuit this year. However, the shooting style is one that requires great strength and is relatively slow.

One result of this is that even some of the world class American archers display a visible tremor as they approach full draw, a giveaway of the stress their bodies are under. This begs the question: can a non-professional archer, who is shooting a few hundred arrows a week rather than per day, pull off this technique in its entirety?

The Asian nations tend to adopt a faster and more economical shot process, and it is hard to argue with their success. Ultimately there are still many ways to shoot a bow successfully and no one coach has all of the answers.

Similarly, no one book is perfect in its entirety. Some of the red pages between chapters seem more like filler than substance, although there are some very useful ones such as the section on making a customized bow grip.

The infamous 1000 arrow challenge features here as well, but we feel it has no place in this book – this is not something anyone but an elite, experienced archer should be doing, and even for such an athlete the risks may well outweigh the benefits.

KiSik Lee has used this book as an attempt to distil what he has learned about archery technique across his career into one volume. Many of the wider aspects of shooting (e.g. setup) aren’t covered in any detail.

But the complete focus on technique allows a level of detail rarely achieved in most archery publications. Overall, the authors’ experience in this area really shines through – the clarity in describing highly complex aspects of physiology and technique is outstanding. This is a book that has a place in any serious archer or coach’s collection.

Archery: Skills, Tactics, Techniques

Author: Deborah Charles

Publisher: Crowood Press. Paperback, 93 pages

This is a wide-ranging book covering recurve target, in full colour, with around 200 photographs and illustrations. It’s focused on recurve target archery as shot in the UK, and wouldn’t be much use for someone starting a different bowstyle.

Deborah Charles is a Master Bowman level recurve archer who has several times been ranked in the UK top 20, and she brings a great deal of competition experience to the party. The style of this book – and one of my favourite things about it – is that it is quite prescriptive. There is little room for that usual caveat in archery advice about ‘you have to find what suits you’ – which is usually true, but generally unhelpful for novices. Charles doesn’t really write that way.

You do this, then you do that (and don’t do this: do that). No-nonsense. The form sections are excellent, considering form cannot really be taught in a book, and most archers could pull something from it.

One of the biggest issues with archery advice, especially in print or web form, is that far too often technical advice aimed at novices, intermediates, serious senior archers and elite professionals is all mixed up together – sometimes in the same feature.

The novice is distracted and confused by the options – naturally they want to go with the ‘best’ choice but that may not be directly relevant to their current standard. Not here. This book, in a standardised series from a specialist sports book publisher, is firmly pitched at the newbie, but also contains a bunch of mini-tips and advice that I haven’t seen in several other books.

While it is aimed at beginners and intermediates, there are lots of useful tips for archers of all standards, and from the point of view of an active competitive archer: there are lots about minor points about etiquette and competitions, some of which are broken out into ‘personal’ tips.

This book will save you a lot of trial and error in that department. It covers every general element of recurve archery I can think of; a couple of things are dealt with too briefly (such as fletching and points) but these really need to be taught directly, anyway.

It also contains a large amount of good advice about actually competing and training to compete, which many other books leave out. If you are looking for a general and practical guide to recurve archery – or something to recommend – take a look.

The Archery Drill Book

Author: Steve Ruis and Mike Gerard

Publisher: Human Kinetics. Paperback, 185 pages.

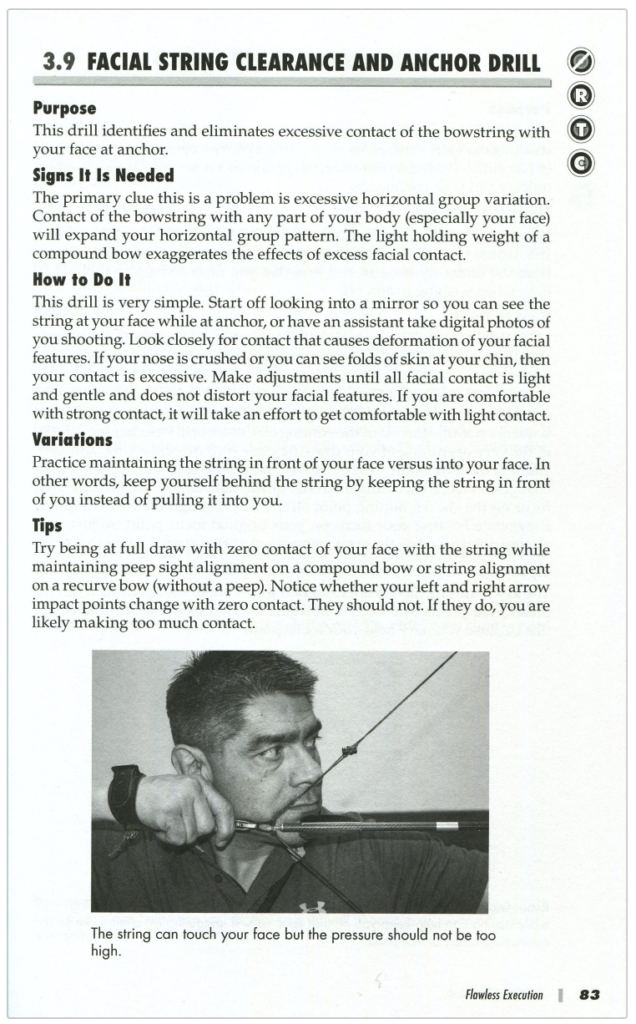

If the previous book is wide-ranging, this one is highly specific. Marketed as the ‘first of its kind’, this book contains 130 drills, exercises, techniques and other routines to improve archery across multiple bow styles.

As you might expect, many focus on strength and form building, but others are geared more towards exploring possibilities (such as with stance, for example).

There are drills for beginners, intermediates and experts alike. They do not focus on gym work; all routines are geared towards using the equipment you have already, with instructions included for making rope bows and balance boards. The book is illustrated throughout with black-and-white photographs and diagrams.

As they put it: “The drills offer concentrated effort towards a a single goal, focusing your body and mind on getting where you want to go.” There is a handy ‘Drill Finder’ reference grid inside the front cover, which marks out which drill is suitable for what: the categories are Shooting, Non-Shooting, Recurve, Compound and Traditional.

Towards the end, there is a specific chapter on ‘ailments’ focusing on target panic and routines for recovery. Some are guest contributions from the pantheon of American coaching greats such as Ed Eliason, Larry Wise and Randi Smith, with the UK’s Simon Needham contributing a fascinating piece on compression practice.

I can’t think of any archer that couldn’t benefit from several of the routines in this book, though some of them are quite arcane and would be best done in consultation with an experienced coach. Indeed, coaches are the audience that would likely find this book essential to maintain interest with students and for us in developing their own programmes.

So all in all, a book for active and experienced archers and coaches working on themselves and others.

interesting the top two books for any recurve archer are not even included on your list, yet two books on the fallible NTS are.

You missed Rick McKinney ” The Art of Winning which is considered an archery bible in the USA, and you missed “Archery” By Kim Hyungtak. Pretty much the bible on how the Korean’s shoot and win podiums year after year.

failed list.

Rather than “The Inner Game of Tennis” I would recommend “The Inner Game of Golf” – they by the same author. The reason is that golf, like archery, is undertaken from a static position with time to setup (and the mind can wander…), whereas tennis can be reactive with little time to think.