Something that could be holding you back is right in your pocket. By John Stanley.

Have you, recently, picked up your phone – or opened a new browser tab on your computer – intending to do one thing, and without thinking found yourself doing something completely different? Has your attention span apparently got shorter recently?

Do you find yourself tapping on an app or clicking on a link without realising why you have done so? Or found it difficult to sleep? Or finishing reading a book? Or starting one?

Let’s get more sport specific. Have you ever been unable to concentrate during a session? Unmotivated to complete a round or achieve a specific goal? Continually distracted or fidgety while shooting?

Archery, when you really hit a groove, is about getting into a state of ‘flow’. Flow is a scientifically documented state when you are operating at your peak: time stands still and you are fully involved and absorbed in an activity. It’s often described as being ‘in the zone’. If you’re anything like me, you may have found this happening less and less in the last few years.

You will find a raft of articles and books itching to blame all these things on smartphones, social media, or internet technologies. Sometimes at least, those articles will be absolutely right.

But it doesn’t usually change your behaviour. We can no longer imagine a world without smartphones and their utility – and their infinite distractions. Vast swathes of people in every society in the world have ultimately become co-dependent with internet-enabled devices.

The good stuff

The list of useful things that smartphones and the internet have brought into our lives is considerable.

Some things specific to archers include scoring apps tuning apps, tracking progress, contacting the club and other archery community groups, filming yourself and others for coaching feedback, keeping training notes and diaries, using a mapping app out to find that out-of-the-way shoot – and sometimes you’ll need the torch, too.

Archers around the world are connected (especially on Facebook), forging new friendships and relationships and deepening bonds set up in real life. We are all still reaping the digital bounty wrought in the internet revolution, and it’s brought some incredible things to the world.

However, it’s incredibly easy to slip into varying degrees of smartphone addiction. It can affect everyone – young and old, smart and stupid, rich and poor. Just like the use of drugs and alcohol, they can trigger the release of the brain chemical dopamine, and alter your mood.

And just as with smoking, addiction is lodged into a more reptilian part of the brain – indeed, as smoking rates decline across the West, with a consequent increase in physical health, a very different addiction has unexpectedly risen up to trouble our collective mental health.

A recent study suggested that most of us are now rarely ever more than five feet from our smartphones.

The bad stuff

Smartphones, particularly combined with social media, have been blamed for all kinds of things in the last few years; most notably, an immense and well-documented rise in mental health issues across the globe, especially anxiety.

There is an increase in the inability to concentrate or focus on tasks requiring specific attention. The number of children admitted to hospital after accidents in public playgrounds has climbed by about a third in five years, according to NHS data – several experts have suggested that some of the increase may be a result of parents being too distracted by their phones and unable to supervise children properly.

Dr Sherylle Calder, a South African vision specialist recruited by the England rugby team, even blames smartphones for a significant decline across all sports in skill and visual awareness over the past six years or so. You’ve probably read about quite a few more.

Blaming technology for social and health problems is not new. But smartphones in particular are a far more adaptably invasive technology, and one we have grown to rely on, perhaps more than anything in modern history.

Most people reading this will have played some kind of computer game either on their phone, a computer, or a console. The best games usually are great at keeping you hooked in some way and coming back; we can even figure out the cunning hook and marvel at it, even while we are nearly powerless to stop playing.

However, we all know it’s a game. Social media is more pernicious than that; because it provides what some researchers have called ‘infinity pools’; an endless scroll of information and ads that literally will never end. It’s harder to perceive it as an addiction.

What has been called ‘the attention economy’ produces constant demands on the brain: often tiny slivers of time, but with each one adding to the cognitive load very slightly. It turns out that the human brain is actually terrible at multi-tasking.

Several recent studies have shown show that people who engage in constant multi-tasking – which can includes checking your phone constantly – have essentially rewired their brains, resulting in lower IQ scores, decreased cognitive performance, and perhaps most frightening of all long-term, a lower capacity for emotional empathy.

Essentially, our phones have turned us into chronic multitaskers, and it can deeply affected some areas of the brain. Putting in the kind of deep work which requires focused attention; whether that is hitting a Master Bowman score or finishing off that creative project you’ve always wanted to do, becomes exponentially more difficult.

But the technological cat is well out of the bag; smartphones and social media are not going anywhere. Most of us cannot give them up for all manner of reasons – am sure you can supply plenty of your own.

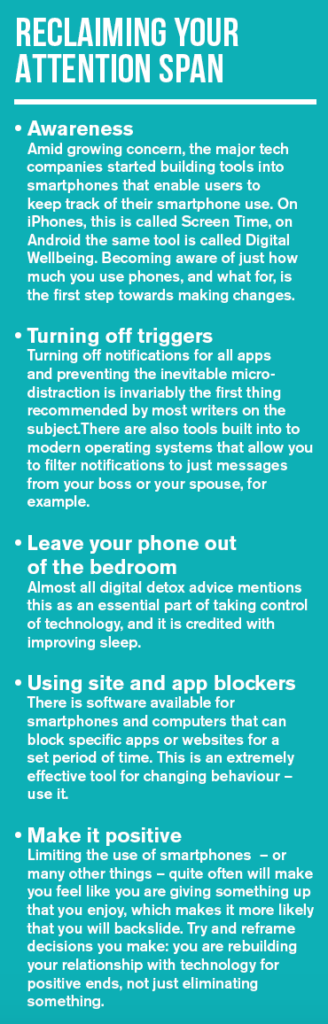

So what can we do?

Getting fit

A good analogy is to food and fitness. In the post-war 20th century most people got an huge influx of processed and fast food, with people in the West having abundant calories for the first time. Naturally, there was an enormous increase in obesity, heart disease and diabetes, which became the primary killers in most countries.

For a long time there was general advice about food pyramids and exercise, which broadly speaking has been mostly ineffective. People know what they should do, but they don’t do it. But if you think of the healthiest and fittest person you know, they will most likely subscribe to a particular philosophy of either eating or exercise.

They make consistent decisions about what they will do and what they will consume, and they do this in the pursuit of feeling their best for the greatest amount of time. In the 21st century, many people are embracing consistent health, exercise and diets, and the levels of heart disease and strokes have fallen concurrently.

Similarly, having a consistent philosophy on how you will have technology such as smartphones in your life is a way out of the forest. This doe The American writer Cal Newport recommends assessing all technology: an app, a gadget, or a digital service – with the question: “What’s the cost in terms of my time attention required to have this thing in my life, and what’s the best way I can use this to support myself?”.

For example: Facebook may bring a great deal of value into your life, but if you spend three hours a day on it, that will cost you many other opportunities.

Could what you need to accomplish there be done in ten minutes of an evening, and would that actually get 99% of the value you would get from being on a service? If you could make that a strict rule (and there are technological solutions to enforce something like that), you could be on the way to owning the technology, rather than the technology owning you.

If you’re reading this, you are an archer, and you don’t need the benefits of archery restating to you. The often-repeated truism that “nothing calms a troubled mind like shooting a bow” was written in a different era, and may not be true for everybody anymore. But the sense of flow, calm and satisfaction you get when you are shooting really well is irreplaceable by anything else.

Indeed, archery and all activities you do just for the sake of them – for the quality, joy and camaraderie – help build resilience in other areas of your life. Papering over boredom with a constant stream of distractions means you will end up avoiding the self-reflection that you need to actually build essential skills – and indeed, a life.

It may also become difficult to teach a new generation of archers; as we all know, the sport requires a slow, methodical study which is increasingly at odds with the faster, connected, results-oriented world.

If you make any kind of new year resolutions for 2020, perhaps you could add one simple on to the list: be aware of the object in your pocket, and just how much hold it may have over you. The effects of taking back control may do far more for you than just improving your scores.

[…] a charged battery on the range, plus opening up the possibility of distraction from training (see this article from Bow 138). It’s worth noting that most elite archers still use good old-fashioned pen and paper; some […]