Tania Nadarajah competed in Den Bosch for Team GB. She reports exclusively for Bow on a competition that was tougher than most – for several reasons.

The 2019 edition of the World Para Archery Championships was the largest competition in its 21 year history, attended by 292 athletes from 52 countries. Held from 3-9 June in s’Hertogenbosch in the Netherlands, it was only the second time the para event was held in conjunction with the able bodied competition, eight years after the first occasion in Torino.

The Championships provided the first opportunity to win quota places for the 2020 Paralympic Games and a change in the qualification system meant that winning those places at this competition was more important than ever. Previously years saw multiple opportunities to secure quota spots – the first being at the World Championships, where the greatest number of spaces within each category are awarded, a chance to top up those places at Continental Qualification Tournaments the next year and a final ‘last-chance’ competition shortly before the Games.

But a new rule introduced by the International Paralympic Committee meant that once a country won quota places in a particular category at this year’s World Championships, they could not claim any more spots in that same category at subsequent competitions. With 80 of the total 140 Paralympic spots awarded at this competition, this was undoubtedly the focus for most countries. (Full qualification details are here).

The week started with a hot and humid official practice day where temperatures topped 34°C in the shade – not exactly the weather conditions most were expecting. However, that evening brought the first in a series of spectacular lightning storms that led to cooler conditions on qualification day and changeable conditions for the rest of the week.

The added pressure on this competition certainly seemed to spur on performances as this proved to be a record-breaking tournament. An astonishing seven world records were shattered on day one alone with further records tumbling as the week went on. Qualification saw two open recurve men improve on the world record with South Korea’s Kim Min Su taking the new record to 662 out of a possible 720 points for the 70 metre ranking round.

“The overall standard has definitely increased,” said Italy’s 2017 World Championship gold medallist, Stefano Travisani. “A lot of athletes here showed that there is little difference between top para and able-bodied athletes now, and a high standard can be reached by para archers too.” And the increased competitiveness made for some tense matches during the elimination rounds.

As quota places were awarded to the top 4 mixed teams in each category – compound, recurve and W1 – failing to reach the semi finals meant missing out on a place for each competitor in the team. Reigning recurve mixed team World Champions, Travisani and teammate Elisabetta Mijno, claimed one of the coveted mixed team spots in a quarter final shoot-off and watching the post-match celebration, you would have thought they had just won championships. Despite later reaching the bronze medal match, Travisani admitted “the quarter final was the most adrenalin-filled match I have ever shot,” revealing just how much was riding on those final arrows.

Major championships often bring the toughest challenges but for para archers, nothing is more challenging than a last-minute change in classification. Australia’s W1 archer, Ameera Lee, was one such casualty – one of three archers to be reclassified at this tournament. Lee was offered a choice of switching to open compound immediately or competing in the W1 category for one last time. “I spoke to my coach, who I have full trust in, and he recommended that I move to open compound straight away as that would give us the opportunity to have a mixed team (with 2016 Paralympic medallist, Jonathon Milne),” explained Lee.

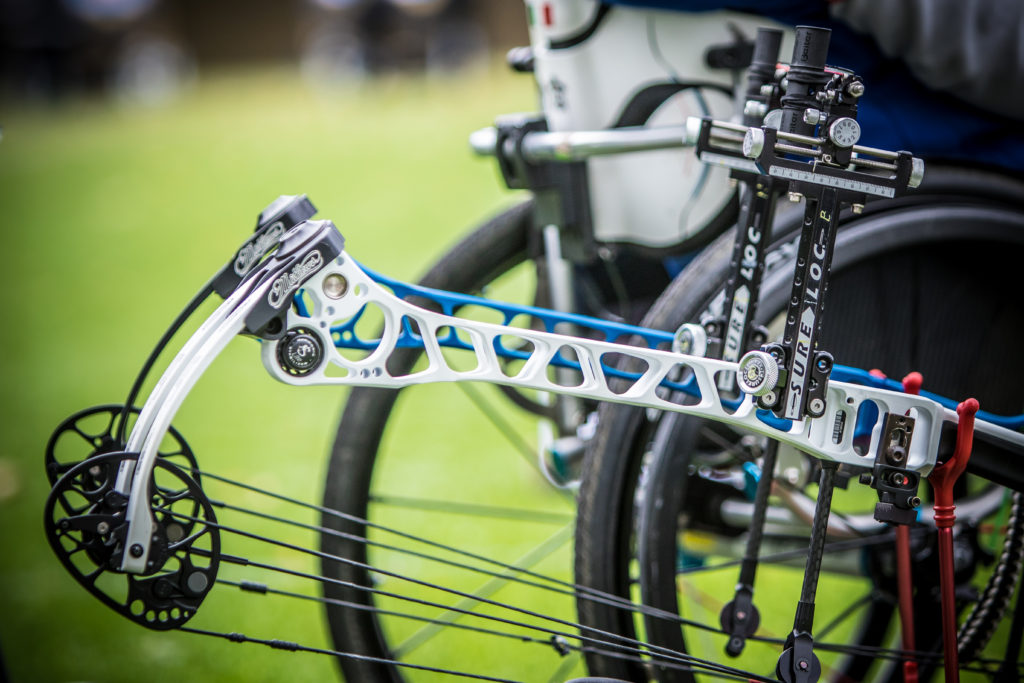

“It all happened so fast that I didn’t have time to focus on the emotions of reclassification so we just went ahead with changing my bow.” W1 archers shoot with a recurve sight and without the aid of a peep or scope so when I spoke to Lee just after her reclassification during official practice, she had less than 24 hours to make the alterations to her bow and compete in a new category.

Changes in classification are not uncommon in the year preceding a Paralympic Games and Lee was not the only athlete to fall victim to rigorous scrutiny. Two visually impaired archers were declassified at this competition and the world numbers one and two in the open recurve men category didn’t even make it to The Netherlands, having declassified at the first leg of the European Para Archery Championships in Italy earlier in the year. “You either laugh or cry in this situation,” Lee said. “Things don’t go according to plan sometimes but you just have to problem-solve and learn from it.”

Problem solving seemed to be a recurring theme for competitors and organisers alike, as issues arose from unexpected places. Unlike the previous combined event in Torino, the para event took place first in Den Bosch which brought about its own set of challenges.

Most teams stayed at a sprawling hotel located in Veldhoven, 25 miles south of the Championship venue. Despite boasting over 500 rooms, only two accessible rooms were available at the hotel so organisers had nine specially-built shower pods installed in the hotel’s ballroom to provide a solution.

“Para archers are used to making do with different conditions in hotels. That’s part of the challenge – finding your own way of adapting to things,” said Roy Klaassen, The Netherlands’ only entrant in the Championships.

The hotel’s distance from the city-centre venue resulted in early morning alarms and long days at the venue. Transport to the field was by coach – a 40 minute journey made even lengthier by the time taken to load athletes in wheelchairs via mechanical lift. And even that was not incident-free, with one athlete being rushed to hospital for facial stitches after falling off a juddering lift.

Things were not so easy at the field either. Ramps were still being hastily constructed at the venue right up until official practice day and only four accessible toilets were available for the approximately 70% of athletes who are wheelchair users. Needless to say, chaos ensued. “It’s clear that the focus is on the able bodied competition,” said Klaassen. “Not enough was done in time for our arrival and that is really disappointing. The intention to host both competitions was good but the execution wasn’t the best.”

While the organisers aimed to achieve a festival-style atmosphere at the venue, you couldn’t help but feel that there was less emphasis on the para event. The exhibitor stalls that lined the pathways of the venue indicated that most of the main manufacturers would be in attendance but the majority of tents remained shut, only opening on the last days when the able bodied teams began arriving.

These challenges are not uncommon but, for competitors who train just as hard as their able-bodied counterparts and want to perform at their best at the year’s milestone event, the issues faced by para athletes before they even get onto the shooting line can be an added stressor, particularly for more severely disabled athletes.

Despite this, the overall competition proved successful. Great Britain’s John Cavanagh, who has been to every World Championships since the first held in Stoke Mandeville in 1998, commented, “These were certainly the most high-profile Para Archery World Championships so far, with a town centre finals field and all the flamboyance of the able-bodied World Championships, so the competition’s status is slowly improving. The last Championships in 2017 (Beijing) was at an isolated sports complex with few non-archery spectators, which has been typical. At the only previous combined event in 2011, the para archery segment was held second, by which time nearly all the other archers and trade stands had left, and there was no city-centre finals field for us.”

The two elements of the sport rarely get together at international events, so for both sides this year was a bonus. The combined format meant para archers were able to meet some of the Olympic and compound archery legends and watch them in practice, while they got to see some of the superb para finals matches on what would also be their finals field. (The exception was the visually impaired finals, which had taken place earlier in the week on the qualification field at The Dukes.)

Moving to the finals field held in the shadow of the gothic St. John’s Cathedral in s’Hertogenbosch’s square certainly added to the drama of the medal matches, which followed the popular format of compounds and W1s shooting on Saturday and recurves on Sunday. And the numerous nail-biting final matches got the live coverage they deserved on BBC Sport’s website and other online platforms – something that was missing from the 2016 Paralympics and may be omitted again in 2020. It shows that not only is the standard of para archery increasing year by year, but interest in this particular sector of the sport is drawing more attention worldwide too. And for the archers themselves, the feeling is that this shift is certainly welcome – particularly if it brings with it more parity across the sport. ■