Duncan Busby takes us through the decisions you’ll need to make when choosing a modern compound bow

Spend the time to find the perfect bow for you, and you’ll reap untold rewards

With the outdoor season just around the corner, many of you will have started thinking about a new set up. A change in season can be the perfect time to make changes to your equipment, and one of the most significant investments you can make is a new bow. But with so much choice available how do you narrow down your search and find one to suit you?

Which Manufacturer?

A major consideration when looking for a new bow is which range to choose from; whether you’re loyal to a particular brand or you base your choice on whichever bow your favourite pro archer is shooting, there are many reasons for choosing a specific manufacturer. Good customer service and a fair warranty will future proof any new purchase and you should always consider how well supported you’ll be if something does go wrong. The majority of bow companies have excellent reputations but it’s worth noting which of your local archery shops sell your chosen brand, as you will most likely be dealing with them should you require any customer assistance. Build quality is also important, but the tiny percentage of bows that do go wrong is really a testament to the level of quality offered by the modern archery industry.

Basic Design

There are many cam options available – you need to find the right one for you

Next you should consider the design of your bow. There is a huge variety of bows available in a range of different shapes and sizes so you need to know which will suit you best. We’ll begin with the bow’s axle-to-axle length.

This choice will be largely dictated by your draw length but personal preference and shooting characteristics will also play a part. Traditionally a bow with a longer axle-to-axle length (38”+) will feel more stable to aim with, and because of its shallow string angle it will especially suit archers with longer draw lengths. Because of their inherent stability, longer-axled bows are considered to be ideal for target archery, however they can weigh significantly more than shorter bows, so the overall physical weight of the bow needs to be taken into consideration when you undertake a full day’s shooting.

Bows with a shorter axle-to-axle length (35” and under) can still feel stable, depending on their riser design, but they are considered to be more difficult to aim with. The bow’s steep string angle can make a comfortable reference point more difficult to achieve, which can eventually lead to inconsistencies in your shot, but this is less of a concern if you have a short draw length. Shorter bows are usually faster and lighter, and as a consequence are more manoeuvrable and easier to carry around difficult terrain. For this reason they’re considered especially suited to field archery.

As bow design has developed, risers have become longer and limbs much shorter. As the majority of their length is largely made up by the riser, these bows are able to provide a more stable shooting platform while maintaining a much lower physical weight. This is an especially good option for those archers looking for a stable but short axle bow to give them the best of both worlds.

Brace height

Pro archers – if you can find them – can give excellent advice

This is the distance between the resting point of the string and the throat of the grip, and plays a huge part in a bow’s speed – put simply, the smaller the brace height, the faster the bow. Now I don’t believe that the speed rating of a bow is particularly important, as the majority of compound target competitions take place at 50 metres, so having a bow fast enough to reach longer distances is no longer a primary concern (many current world records were shot with older, ‘slower’ bows).

Brace height is largely dictated by whether the riser is deflex or reflex in design; the more reflex the riser the smaller the brace height. As bow speed is a major selling point in the industry, the majority of bows on the market today are reflex. But the riser design and its brace height can determine much more than just speed.

The larger brace heights found on deflex risers, where the throat of the grip is forward of the limbs’ pivot point, are traditionally thought of as being more forgiving and easier to shoot. Their design is particularly suited to target shooters and those with longer draw lengths who are less concerned with arrow speed and instead favour a bow which is easier to control.

A brace height of between seven and eight inches is considered to be perfect for the majority of archers across all disciplines, because it gives a good balance between arrow speed and forgiveness.

Limbs

Split limbs make for a slightly lighter bow

Just as riser design plays a huge part in a bow’s shooting characteristics, limb design can also drastically affect how the bow feels and performs. There are a wide variety of limb designs available from solid or split to parallel or non-parallel. Each manufacturer usually has their favoured design, so often the choice is made for you, but limb design can be divisive. There is little difference in terms of performance; split limbs tend to have a wider profile so are considered to be more stable and better resistant to instances of ‘cam lean’, they also weigh a little less so are a good option if you are looking for a lighter bow. Older solid limb designs are often considered to be sturdier, and as they remove the need to match limb deflections, which is crucial for keeping ‘cam lean’ to a minimum, they have a loyal following.

Another decision is whether you want parallel or non-parallel limbs. Parallel limbs look like they are sitting at right angles to the riser and have become more popular with bow companies, this type of limb is quieter and gives less vibration in the shot; as a result though this can deaden the feedback of the bow and make a bad shot harder to recognise.

Non-parallel limbs are a much older design; these limbs look a lot straighter and give you a lot more shot feedback, although as a result they can cause a little more vibration. Despite this they do not make the shot uncomfortable, non-parallel limbs are also much better at resisting hand torque which makes them a favourite amongst target archers or those archers looking for a little more consistency.

There are some companies who also offer a past-parallel limb, these are usually split limbs and are pre loaded to make them look almost as if they are bending in on themselves. Past-parallel limbs are used on the faster bow models and offer super-speed and power with minimal vibration, they share many of their shooting characteristics with their parallel counterparts but are mostly found on hunting bows where a compact bow design is more desirable.

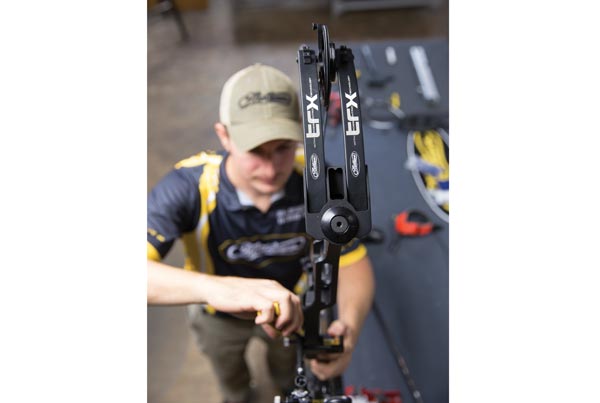

Cams

Parallel limbs are usually quieter with less vibration

There are four main types of cam on the market today; Twin, Single, Hybrid (also known as “cam and a half”) and the modified twin cam system or binary cam. Each have their own set of advantages and disadvantages and will ultimately determine your bows performance. Most bow manufacturers will have a preference for a particular cam system, and although some do utilise all styles, your choice of cam system may be determined by your brand choice.

Single cam

The most basic of these systems is the single cam; this system uses an asymmetric cam attached to the bottom limb with an idler wheel on the top limb. It is only the cam on the bottom limb that is doing any work while the wheel at the top acts as a runner for the string. Single cam bows stay in tune longer and require less maintenance, but although they are easier to set up and tune, single cam bows can be a little slower than bows that use other cam systems. They can also suffer from poor nock travel; this is how straight the arrow’s nock point travels from full draw to brace height on release – the straighter the nock travel, the better the arrow flight and the easier to tune. As a result, single cams are found on fewer models each year.

Twin cam

One of the oldest cam systems is the twin cam; this uses identical cams on the top and the bottom limbs, as a result the cable and string system is much simpler than that of the single or hybrid cams. Twin cams deliver higher arrow speeds than most other designs and once set up can give one of the better nock travels. They do however require some work in order to get the cams rotating at the same time and once set are prone to coming out of sync, so may require more maintenance. This style of cam has made a bit of a comeback in recent years with the benefit of improved technology, which has helped to reduce the tuning issues.

Hybrid cam

One of the more common sights on the modern shooting line is the hybrid cam, made popular by the ‘cam and a half’ system. This system works in a similar way to the single cam but instead of an idler wheel, the top limb has a cam which is an ‘almost’ identically shaped one to the one on the bottom. This system is designed to give you the practicality and easy tune of the single cam while being as fast as a twin cam. In reality, this system is faster than the single cam but does require some synchronising. Once set up though, this system is very easy to shoot and tune and should require only a little more maintenance than a single cam.

Modified twin cam (Binary cam)

Non-parallel limbs can increase consistency

The modified twin cam or binary cam system is relatively new when compared to the other systems and comprises of two identical cams which are slaved together through the cables rather than through the limbs; this makes it almost impossible for them to come out of sync. These cams are very easy to tune and are low maintenance as once set the cams will stay in tune for the life of the strings. They give good arrow speeds and the best nock travel of all the cam systems, but due to their design they can cause problems with cam lean. This type of cam has increased in popularity recently with several manufacturers offering their own take on the system with added technologies to help tune out any unwanted ‘cam lean’; this is when the cams do not sit straight at full draw due to uneven forces in the cables. As a result the binary cam has become a firm favourite amongst archers around the world.

The cam’s main job is to control the draw length and let off; the let-off reduces the draw weight by between 55-80% at full draw, depending on the system. But the amount of let-off you choose is mainly down to personal preference; an 80% let-off will be effortless to hold but it will make the bow easier to torque and it will be more affected by bad weather. A 55% let off will take more effort to hold, but will sit better in the wind and will be harder to torque. As a result most archers choose around 65% let off as this gives you the best of both worlds, but it’s a good idea to look for a cam design that allows you to easily adjust the holding weight across a range of different options.

Draw length adjustability is another important feature to consider, these days most cams come with some level of draw length adjustmen. This is usually achieved by rotating the module on the cam rather than replacing it with a different cam entirely, as was previously the case. If you are certain of your draw length then this feature will be less important but if you are likely to make adjustments then I’d recommend choosing a cam with a good amount of adjustability.

Cams not only play a part in the speed of the bow but also in its overall ‘shootability’; this is how well the bows stops and holds at full draw. The cam wall, which is the point at which the bow cannot be drawn any further, can feel hard or spongy depending on how much give there is in the cam, there are an increasing number of cam designs that offer a customisable wall so you can set the bow’s stop to suit your particular shooting style.

Choosing a compound bow can be a daunting prospect. But if you find yourself stuck, a safe bet is to go down the middle: a bow with a 37”-38” axle to axle length and a 7” brace height will suit most archers and will perform well in any discipline of archery. There are lots of bows around this specification; just remember to choose a good quality and reliable make. Get it fitted to you correctly by a competent shop and make sure your new bow has a good amount of adjustability so it lasts you a while.

If you are struggling to make a decision on your next bow I would recommend getting some advice from any archery pros you can meet, they have a wealth of information and insight into the bows that are being marketed, and can impart a lot of useful but lesser-known information on setting up and shooting your equipment.

The latest developments in bow design ensure that we now have access to some of the most efficient and advanced archery equipment ever produced, so there’s never been a better time to find your ideal bow.

This article originally appeared in the issue 123 of Bow International magazine. For more great content like this, subscribe today at our secure online store www.myfavouritemagazines.co.uk