Jan H Sachers digs up the past

Roughly 12,000 years ago, a climatic change in Europe led to higher average temperatures, warmer summers and generally beneficial conditions for a great variety of fauna and flora to prosper. Plants and animals hitherto only known in more southerly regions began to slowly migrate north, and in this process, which lasted several millennia, the yew tree (Taxus baccata) eventually made its appearance in the Alpine region.

Its superior qualities were soon recognised by the bowyers of the time, and from the area of modern- day Switzerland alone, more than 50 bows or fragments have been recovered and dated between circa 4500 BC to 2000 BC, making the small country the world record holder in Neolithic bow finds.

During the Mesolithic age, elm (Ulmus glabra) had been the wood of choice for building bows, and the perfect design for this material featured a deep and narrow grip section with wide and flat limbs, as exemplified in the famous Holmegård finds (Bow, February).

It appears that once available, yew was readily accepted as the perfect wood for bow building, but the by then well-established convictions of what made a proper bow were a lot slower to change.

Archaeological finds, for example, from Ochsenmoor, Vrees and Bodman (Germany) or La Draga (Spain), and dated as late as 1500 BC, were made from the ‘new’ material, but still featured the pronounced grip section and wide limbs, betraying the adherence to a millennia-old tradition.

New material, new design

Most of the bows and fragments in Switzerland were discovered in the context of Neolithic settlements that had been built near, or sometimes in, lakes, with houses on stilts. During this phase of human history, which in this geographical region lasted from about 5000 BC until 2300 BC, people gave up their semi-nomadic lifestyle as hunter-gatherers and settled down in permanent dwellings, discovered agriculture, domesticated crops and animals, and began to raise livestock.

The so-called ‘Neolithic Revolution’ also brought improvements in tool-making and pottery, specialisation and division of labour, an increase in trade and many other benefits this sedentary lifestyle had to offer.

Nevertheless, hunting still played a huge part in feeding an ever-growing population, and besides spears and traps, bows and arrows remained the preferred weapons. However, the Neolithic yew bows from the Alpine region differ from the more northerly Mesolithic elm bows in practically every aspect of their design.

Yew is superior to any other European bow wood because its dense, pressure-resistant heartwood and softer, stress-resistant sapwood combine the two desired qualities of any bow- building materials. The best wood comes from trees that have grown slowly, in the shade or at high altitudes, of which there are, of course, plenty in the Alps. The narrower the growth rings, the more power the finished bow will have.

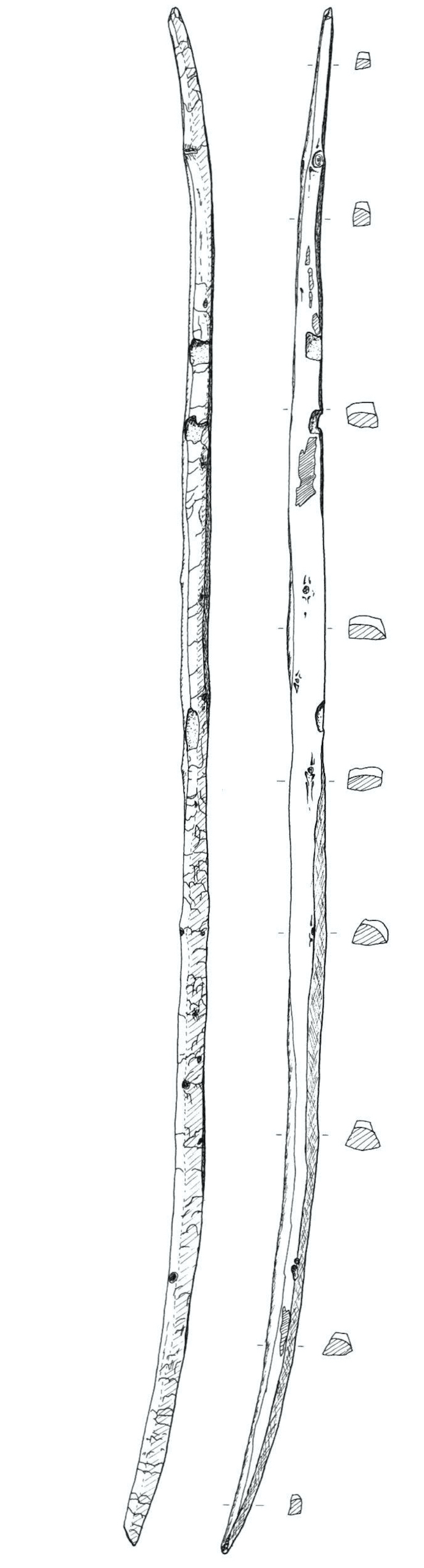

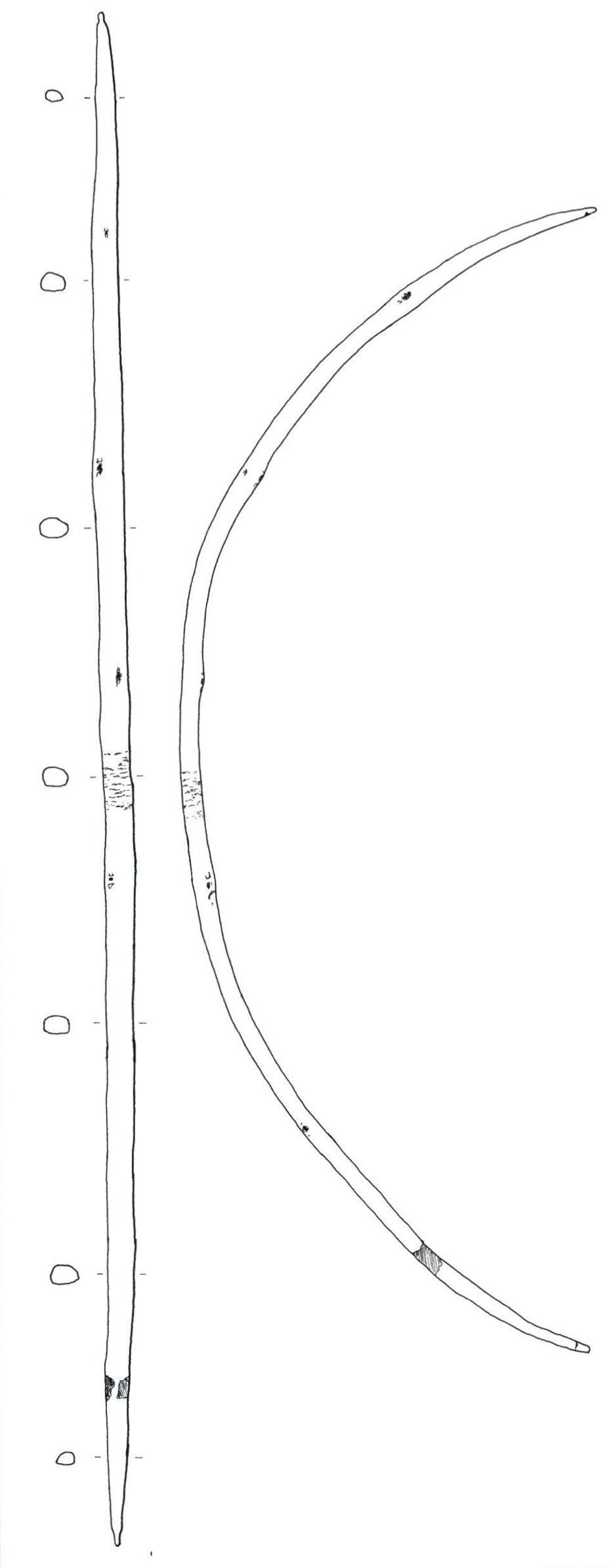

With these qualities, there is no need for wide limbs in order to reduce the risk of breakage. The ideal shape for a yew bow is that of a long stick with a flat back, consisting of a thin layer of sapwood and a heartwood belly of a high-stacked D-profile, tapering evenly towards both ends. It is, however, necessary to keep the outer growth ring on the back intact, and to leave the material around any knots, which constitute potential weak points.

Mesolithic elm bows were made from small tree trunks of perhaps 5cm to 6cm diameter, with their natural curvature forming the back of the bow, so a tree would yield material for only one bow, or two at the most.

In the Neolithic age, larger trees were often split longitudinally into quarters, eighths or even smaller portions, each of which was then worked with stone tools such as axes, adzes and knives, which left tool marks that are still visible on some of the finds. Others had a smooth surface, which was achieved through the use of sandstone and horsetail (Equisetum).

The wood was used fresh, which made it easier to work with. Ideally, the finished bow would have been left to dry for a few days before attaching a string and test-bending it, but this rule may not always have been followed.

Ötzi the Iceman

Ötzi, often known in the media as ‘Ötzi the Iceman’, is the natural mummy of a man who lived between 3350 BC and 3105 BC, discovered in September 1991 in the Ötztal Alps on the border between Austria and Italy.

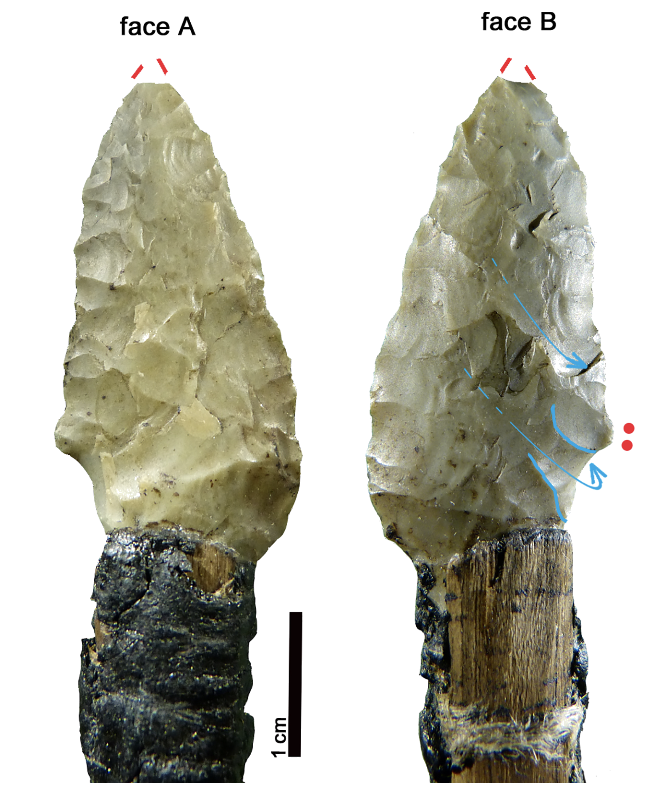

Most scientists now believe that Ötzi was murdered, due to the discovery of an arrowhead embedded in his left shoulder and various other wounds. The nature of his life and the circumstances of his death are the subject of much investigation and speculation.

An enormous amount of archeological attention has been focused on the body and the possessions found with it, which has found out details of his origins, his last meal (which included ibex meat and bread) and possibly his profession (he may have been involved in copper smelting).

He also had 61 tattoos, mostly of simple black lines, and a relatively sophisticated ‘survival kit’ along with possible snowshoes. Ötzi is Europe’s oldest-known natural human mummy, offering an unprecedented view of Copper Age Europeans. His body and belongings are displayed in the South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology in Bolzano, South Tyrol, Italy.

Visit: iceman.it

Bows and staves

Not all the bow finds from Switzerland have been documented or dated properly, but all can be attributed to the Neolithic phase of human history, roughly between 4500 BC and 2000 BC. While following the same general design principles, the individual examples differ in detail.

Most measure between 140cm and 170cm in length and probably had draw weights between 60lb and 70lb, although lighter bows of perhaps 35lb to 45lb were also found. Some had flat or even concave bellies, but the greatest differences are found in the tips. Apparently none of the more than 50 bows discovered so far had string grooves cut in. Instead, the string rested on shoulders, while the protruding tips could take a number of different shapes: conical, rounded, spoon- like and others.

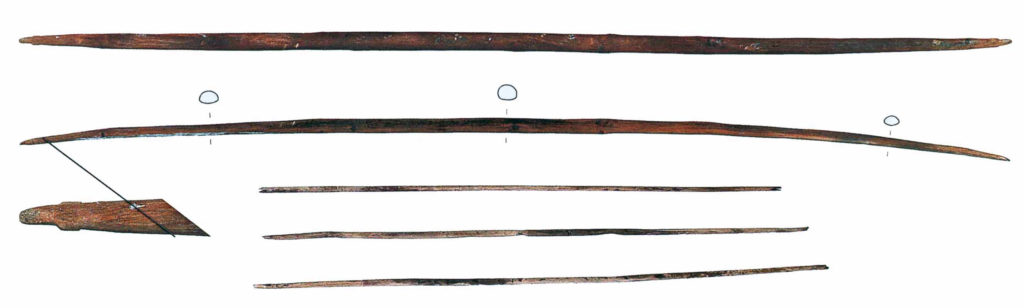

The most famous Neolithic bow belonged to ‘Ötzi the Iceman’, the mummy of a man who died around 3258 BC (±89 years) near the Tisenjoch in the Ötztal Alps. It is unfinished, a yew stave of 180cm length showing tool marks from an axe with a copper blade or a flint-stone knife, both of which were found in the man’s possession. No means to receive the string had yet been formed, and it is unclear whether the sapwood was completely removed from the back or is just no longer visible due to discolouration.

Half-finished staves were also found elsewhere – for example, in Twann (approximately 3800 BC), Feldmeilen (around 3725 BC), Nidau (approximately 3000 BC, burnt) and Zürich-Mozartstrasse (around 3100 BC). The latter was 160cm to 170cm long and worked very carefully, but a large knot on the back some 40cm from the tip either caused it to break during a premature bending test, or the bowyer broke it deliberately in anger.

Some bows were smaller and weaker, most probably intended for children; these were also made of yew wood, albeit from thinner branches, and of the same quality. The smallest ones were found in Horgen and Zürich-Mozartstrasse, dated to circa 3100 BC and only 46cm and 57cm long, respectively. Other examples were in the 80cm to 100cm range, and those between 120cm and 130cm in length may have been strong enough to hunt small game.

Neolithic archery culture

Ötzi carried an almost 200cm-long piece of twine made from three twisted strands of leg tendon from an unidentified animal, which some believe may have been intended for use as a bowstring. However, the majority of Neolithic bowstrings were more likely made from plant fibres, which were of virtually endless supply, much easier to come by, much easier to process and at least as suitable for the task. Experiments have shown flax or linseed, nettles and other materials to work well, even with stronger bows.

While bows and arrows were mainly and originally made for hunting, they could be used against fellow humans as well. Ötzi had a stone arrowhead stuck in one of his shoulder blades, and human skulls and bones from the Mesolithic and Neolithic ages with embedded arrowheads have been found all over Europe.

Small chisel-shaped arrowheads were still in use during the Neolithic age, but most arrows were equipped with two-bladed triangular heads with or without barbs. They were made from chert or flint, inserted into a shallow slit in the shaft and secured with pitch.

Arrows with blunt cylindrical heads carved from wood or antler were used to hunt small game and birds. Conical heads made of bone were probably intended for medium-sized game but were also used against humans, as demonstrated by a skull from Porsmorse (Denmark) that had one embedded in its nose cavity.

Shafts were made from many different types of wood, but Viburnum, also known as arrowwood, appears to have been preferred. No fletchings have survived, but we know they were glued on with birch pitch and secured with wrappings of plant fibres. Ötzi carried 14 viburnum arrows originally fletched with duck feathers in his deerskin quiver.

Archery clearly played a major role in Neolithic culture in the Alpine region, as demonstrated by the archaeological records, which not only contained a large number of well-made yew bows for all ages, but also specialised arrows, quivers and other associated equipment, such as thin stone slabs, which may have been used as bracers.

It is noteworthy that other types of yew bows have also been in use during this period – for example, the ‘paddle-shaped’ flatbows from Meare Heath and Ashcott Heath in England. But the design of the finds from Switzerland and the Alpine region proved ideal for the material, and thus remained in use long after the end of the Neolithic age and enjoyed an illustrious career all through the Iron Age and the Middle Ages, up to the famous English longbow, which still features characteristic attributes such as the sapwood layer on the back and the high-stacked D-shape profile.