The ‘strongest’ bow in the world? Kristina Dolgilevica investigates.

The Korean gakgung literally translates as ‘horn bow’. In comparison to its other traditional counterparts, it is considered to be the most advanced bow in terms of its engineering. A horn bow comes under the Asiatic Composite bow group. It is a laminated bow; a traditional bow that uses layers of horn, wood and sinew.

When these layers are glued together they provide for highly effective energy storage and high energy output on release, hence why it is considered the ‘strongest’ bow (and not because it shoots highest poundage than other bows).

At the other end of the spectrum are ‘self’ bows – the English longbow being the prime example. Due to their straight shape and the properties of the materials used, self-bows need to be long and thick in order to match the power and output of a laminated bow.

The bulkier the bow, the more energy will stay within it, since the energy is stored in the limbs. Those of you who have shot both longbow and any other short composite bow, will likely say that a 45lb longbow feels stiff on release, whereas a laminated horsebow with the same poundage, feels smooth, light and fast.

There are of course performance drawbacks with any bow. For example, having more mass to the body of the bow makes it more stable in the hand – a plus for a self-bow, while a short, light composite will require a lot of body control from the archer.

I am not implying that self-bows require less technique or physical strength; but because the composite bows are practically weightless in the hand, they will also be less forgiving for technical fault or inconsistency. Composite bows are also far more difficult and expensive to manufacture.

Bow Shape

Aside from the unusually deep reflexed limb, what makes the Korean gakgung superior to its composite brothers, is the additional recurved ‘ear’, or tip of the limb.

These ‘ears’ curve away from the archer, allowing for an even longer draw length, more energy storage and stronger spring/recoil on release of the string. This adds even more speed to the light and fast bamboo arrows used.

Long before the turn of the 17th century (times when the mechanical weapon replaced the bow), Korean armies were reliant on the bow as their primary missile weapon, and all of the engineering features of the bow would allow for an extended assault range.

A close relative in limb profile, ‘ear’ and material to the Korean horn bow is the Chinese composite, commonly known as the Manchu style bow. But it has a longer, thicker body and limbs, therefore, when drawn, results in a smaller (bow) body recurve even with a thumb overdraw.

This bow was usually paired with a heavier arrow and was therefore used for penetrating targets at closer range than the Korean bow, which was used more as a distance weapon (like the longbow in its European military heyday).

Bow Materials

A typical gakgung consists of a wooden core with horn glued to the belly of the bow (the side facing the archer) and sinew on the backing (the side facing away from the archer). Flexible absorbent woods are used for the core and limbs: oak (handle), maple, poplar, bamboo (core), and mulberry for the ‘ears’.

The belly is typically inlaid with water buffalo or ox horn. Cattle horn in general has tremendous mechanical properties. When used on the bow it is tasked with compression, i.e. it has to be both flexible and strong to bend inwards and back to its original state.

In addition to a relatively high water absorption, a property that allows for manipulation of the material, the pores of the buffalo horn in particular are more fibrous and allowing for linear compression, i.e. it can be bent to the shape of the bow’s curves.

Buffalo and ox horns are often long, so that just one or two pieces is enough to cover the whole belly, making it more uniform. Only a quarter of the outer part of the buffalo horn is used, and that will be enough for one bow. Smaller pieces of horn are used for the gakji (horn thumb rings).

Keeping the bow’s shape in mind, if you think about the bamboo fibres they also follow a longitudinal trend. This is why it is extremely important that the limbs do not twist at any point and an archer must inspect the bow and bow’s temperature frequently, especially if they don’t shoot often and during the cold winter season- the time when bows break the most!

The backing side of the bow is inlaid with layers of sinew – ox or cow tendon. This is a tough, fibrous connective tissue that can withstand the pulling force and is very flexible. The washed and dried tendons of two cows are needed for one bow.

For extra waterproofing, the backing is often covered with birch tree bark, or on rarer occasion, leather. All these components are glued together with the fish air bladder glue. This glue is also known as isinglass, commonly extracted from a sturgeon, and has been in use since classical antiquity, at least from the 8th century BC.

Bow Making

Traditional bow making in South Korea is a seasonal affair, and new bows are made in wintertime. Korean winters are long, cold and dry – perfect weather conditions for bow making. It takes around four months to make a new bow and this type of weather allows for natural cooling and drying processes.

This climate also produces superior traditional arrow material: Sasa coreana, known as ‘arrow bamboo’. It grows throughout Korea, and according to fletchers, the best type grows in the northeast, where the cold makes it grow slower and the coastal sea wind makes it straighter.

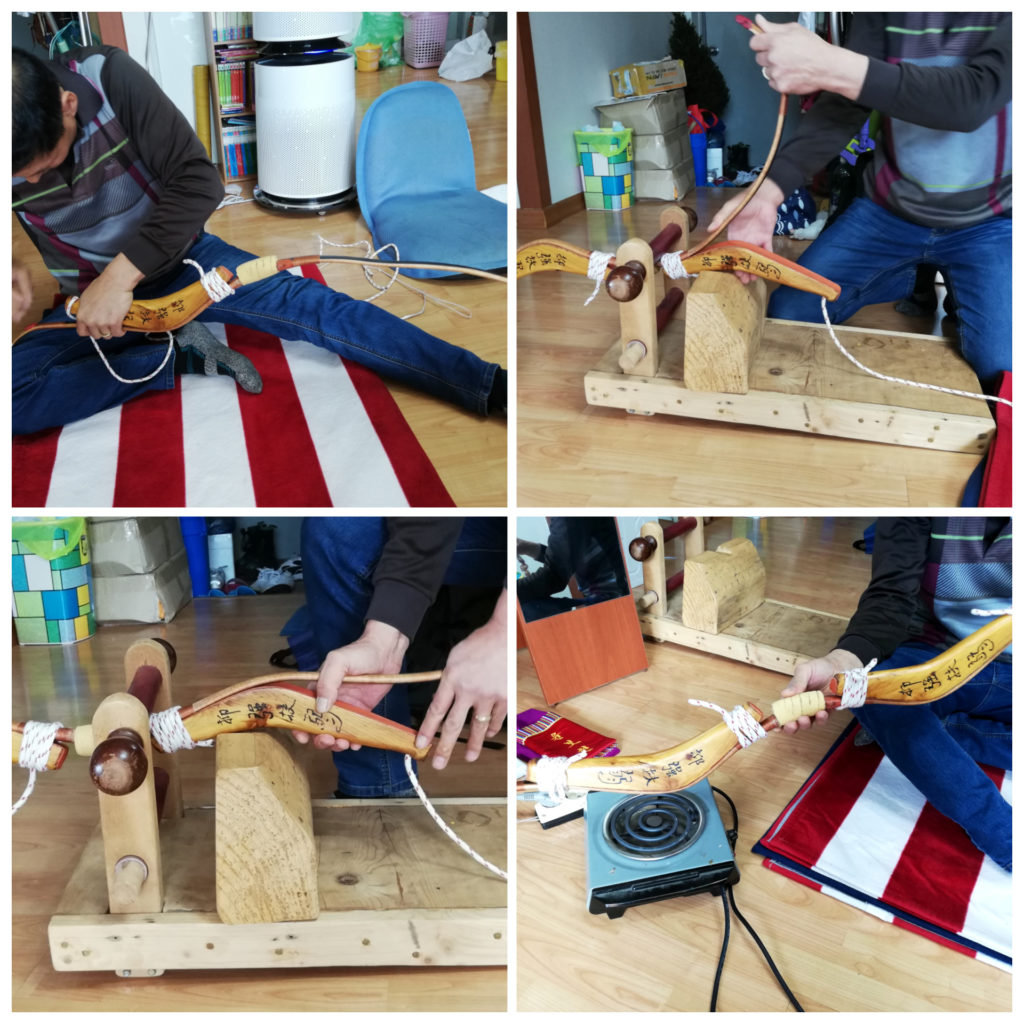

During the process of making a bow, a bowmaker will subject the bow materials to both cooling and heating treatment, readjusting them individually many times until they achieve their characteristic shapes. All materials used in bow making are constantly bent and shaped over a charcoal fire until the bowmaker is happy and deems them suitable for gluing.

When all materials are finally glued together, they will be bound with a rope and dried for 20 days at a temperature of 25-30°C; this is followed by further manual shaping. Each bow will come out as a unique piece; the bow grip and the thumb ring will be personalised to user’s hand and thumb. To complete one product, the bowmaker will touch the bow more than 3700 times over those four months.

It will take more than ten days for a fletcher to complete one arrow – a 50 step process. Traditional bow making demands for a great set of skills, experience, patience and physical strength. As an traditional artisanal skill, despite being protected as an intangible cultural asset by the Korean government, it is a correspondingly rare career: there are now only ten active bowmakers in South Korea today.

Bow Preparation

Since bow making is a lengthy seasonal process, I did not have the opportunity to observe it in full on this trip. I was however treated to a personal demonstration of bow preparation by my friend and bow maker, Bo Hyun Yoon, who has a couple of decades of shooting and bow making under his belt.

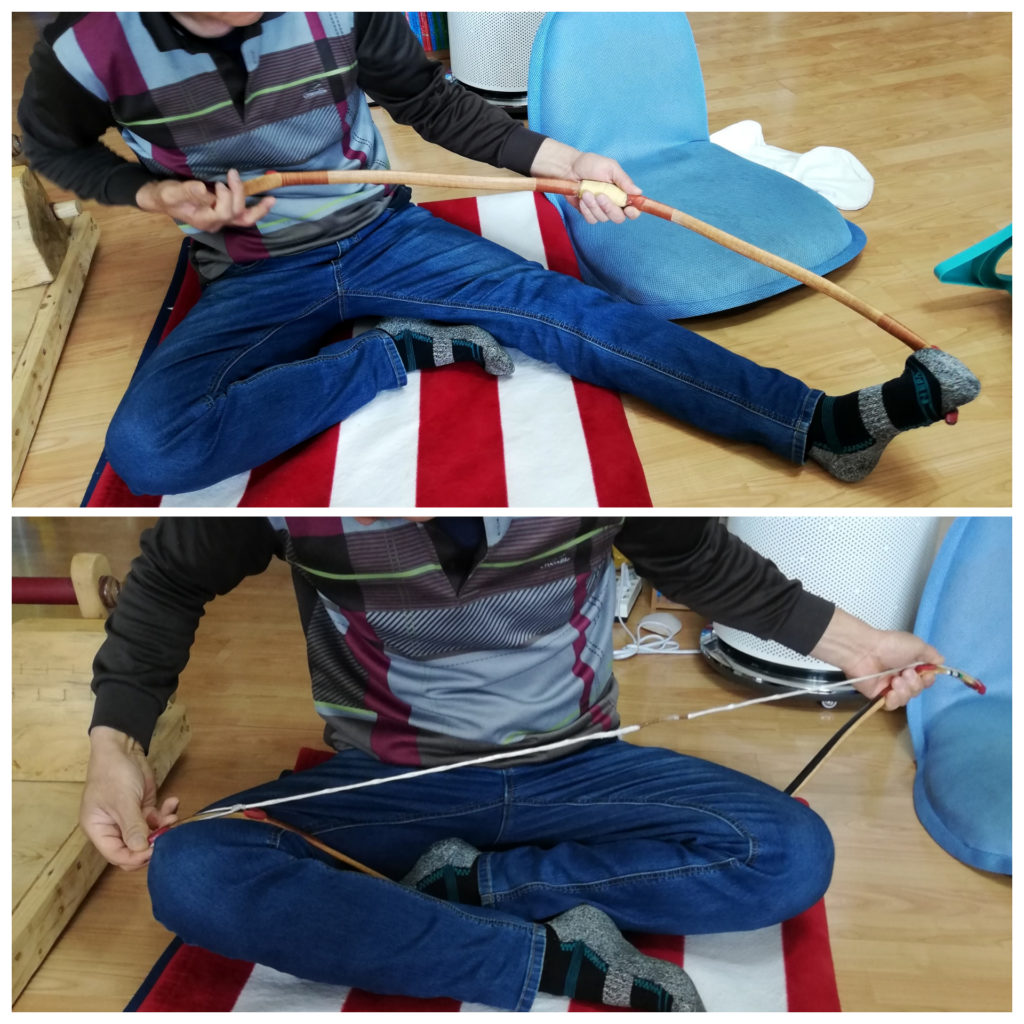

Recurve archers should never again complain about having to set up their rig, because it takes on average around forty minutes to prepare a traditional bow for shooting. A novice may spend up to an hour, because they will have to get acquainted with the bow’s shape and learn to treat it with care so it doesn’t break.

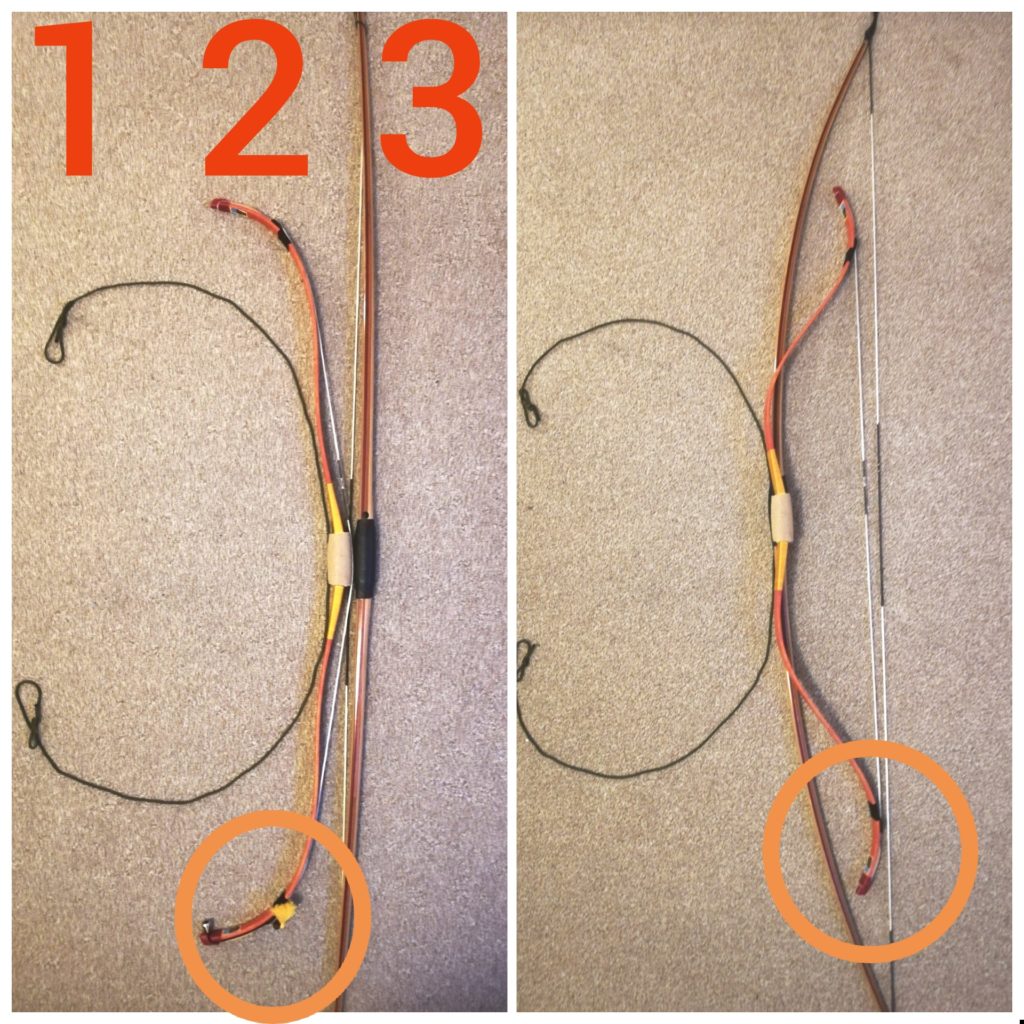

There are two ways of stringing the bow: first, by using your body, second by using a gungchang – a specialist fixture that assists in stringing and is used by most archers. All archers will store their bows in thermal boxes, either at the clubhouse or in their home.

Most will have a wooden thermal box at home because they would often need to prepare their bow for shooting at a competition, where there would be no space or time to do so. These boxes are often made by archers themselves and are known as jum hwa jang. Temperatures at which the bows are kept vary from 21-25°C.

The archer will first take the bow out and unwrap it; the bow will be bent outwards into a crescent shape. Archers use a portable electric hot plate and will hold the bow over its heat to soften the glue. The archer will listen to the sound of the bow and look for a certain

shape, as they manipulate the bow. The ideal conditions for this are a silent room. It needs to be done in silence because each bow will have its characteristic sound, both when it is shot and when it is strung. If a sharp cracking sound starts to appear, the archer will know to heat that part of the bow more to warm the glue and get more elasticity out of the bow.

A gakgung is strung in two stages. First, the bow will be straightened halfway up, its shape will be very much like that of a modern Korean practice bow when it is unstrung, i.e. the main body only slightly bent away with ‘ears’ pointing outwards. Special wooden blocks are tied on one limb at a time.

These blocks are known as do ji gae and are custom-made to each bow because they help understand the shape of the limbs, and every archer will heat and bend their bow to fit that particular mould. This process is careful and slow and requires a lot of concentration- one slip up and the bow will bounce back.

This is what happened during my friend’s demonstration, because he had an injury to his hand, but luckily the bow was fine because it was sufficiently loosened under heat, and he then proceeded to use the bow fixture to assist him. It does require a lot of physical strength to string a gakgung by hand.

When both limbs sit in their moulds, the archer will then put on the string on the top limb, followed by the bottom. The blocks are then untied and further adjustments and shaping takes place. These are done with the help of archer’s hands and feet.

When bow shape looks perfect, ‘rule of thumb’ brace height check must be done. It is measured like so: bottom part of a fist is placed in the deepest recess of the bottom limb of the bow, thumb up. The tip of the thumb must touch the string.

The same check is done for the top limb, only there the thumb almost reaches the string with a 3-5mm gap. The lower limb will be set stronger because of the nature the thumb draw. When the bow is strung the archer will put on limb savers at each end, usually short leather ring straps.

The archer’s belt which is used as a bow case and a quiver, tied around the waist when shooting, will act as a bow guard. It is tied around the bow in a traditional manner to be ready for transportation. Bows are tied like that for every competition, and when novice archers are first presented with their bows upon entering the Korean Traditional Archery Association.

The Korean bow today

Since my return from South Korea, I’ve been frequently asked one question: how come I can’t buy a traditional bow like that abroad? Firstly, the bow itself is designed to perform at a long distance and judging from my own experience there would be no satisfaction using it at a distance shorter than 100 yards, especially when traditional anchor points and thumb draw are used.

Secondly, shortage of bow materials and import restrictions that apply particularly to the buffalo horn. More recent issues arose in 2005, when the Korean government imposed severe restrictions on buffalo horn imports from their main supplier, China, putting traditional bowmaking practice at a high risk of total extinction.

Issues have been somewhat resolved, and thanks to the pleas and campaigns of many individuals, the traditional bow lives. But there are now just 400 active traditional clubhouses in the territory of South Korea.

Next month I will investigate the popularity of KTA discipline and the culture of KTA competitions.

Special thanks to Sora Kim, Bo Hyun Yoon and Oh Jung-Kwon.

Love it need more

I am Spanish and I live in Spain, I am interested in the Korean bow,