Kristina Dolgilevica’s KTA adventures continue

I returned to Korea to put my skills to the test in competition. Here, I finally achieved my goal of representing my club and Seoul city on Korean soil, impressed with my shooting form, led the scoreboard, got a prize medal and became the first western female to formally take part in the District and the Korean Traditional Archery (KTA Women’s National Championships).

I will not go into the depths of history here, nor discuss the informal competitions (games); information on those is readily available in Professor Thomas Duvernay’s book on KTA. My aim is to provide an insight into the experience of being involved in a formal, traditionally run competition. It is a uniquely Korean world, with its own pace and rules, one where westerners don’t usually go.

Formal Competition: Types

Most common types of formal competitions are district, inter-city, national and grading events. District competitions are very popular and populous, partly because logistically they are more convenient to attend. Here, all the local clubs in the city or province compete against each other in a series.

These series normally take place twice a year, but dates are not fixed, and they are largely dependent upon weather conditions and the ability of the venue to host a said number of people. District competitions typically take place after the rain season (Jangma), when the summer heat has subsided – that is, from around mid-October into November, with another series in spring.

Participating clubhouses host in rotation or in a pre-agreed order. This not only provides the challenge of varying shooting environments, but it is also symbolic of the host’s courtesy to its guests. Each venue will put a lot of effort into organising and catering for all its participants. A venue can host twice or more during the series if the budget allows.

These competitions are completely free to competitors, and no one leaves hungry. Clubhouse presidents will arrange the financial side of things at special meetings, which can involve local dignitaries, businessmen or politicians, to help fund or cover some or all of the expenses. Aside from any personal achievements, it is a good way for the clubhouses to build reputation, qualifying for bigger events and earning general kudos among their peers, the locals, and the nation.

I took part in eight separate events across a period of six weeks. Seven of those were district championships within Seoul and its periphery, and one, the Traditional Archery Women’s National Championship, is the most important women’s event in the calendar. For the district series, I represented my clubhouse, Gonghangjung, and shot at five different locations (returning to two of those twice). For the Nationals, I represented the city of Seoul and its province, competing with women from across the country.

Requirements & Grading

To compete in any formal competition in South Korea you must be a certified member of the clubhouse, wear appropriate uniform, shoot the bow appropriate to your level and have a basic understanding of the Korean language. Once you have become an active member of the clubhouse and have proven that you can shoot at 145m distance, you will receive your clubhouse belt. Belts are unique to each club, and must be worn at all competitions and during practice.

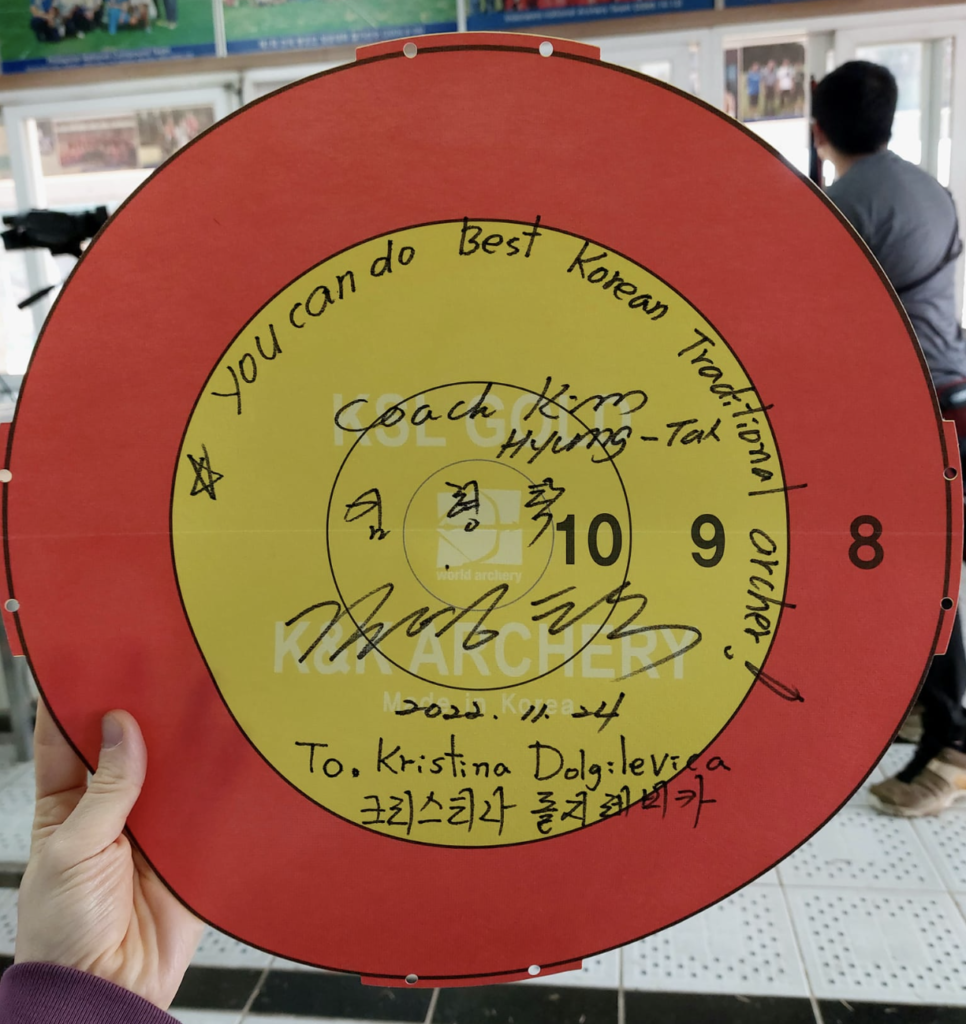

The belt bears your clubhouse name and district, as well as your own name. Korean names typically consist of three syllables, so are easily embroidered; however, it is also usual to put your nickname down. Nicknames are given to you by your master and typically refer to your characteristics. Mine was given to me by my teacher and mentor, Kim Hyung Tak, and reads ‘sujon’ (熱薑), meaning, ‘crystal rock’, referring to my rock-hard discipline and the fact that ‘I shine’, always exhibiting a positive attitude around others.

Any archer not wearing the appropriate attire, for example all-white with the official federation shirt, will not be allowed to compete. Small details, like brand logos, are acceptable. I had to borrow my friend’s wife’s uniform for the first two competitions, as I had returned to Korea from Turkey a couple of days before the KTA tournaments, where I represented the UK at the World Nomad Games.

The trousers were three sizes too big and the shoes a size too small, but I was grateful and made it work. I received my own official shirt from Mr Lee, the club competition manager, and purchased all other necessary items to meet the requirements for the rest of the events. It was the first time I have enjoyed the formality of uniform.

The belt also exhibits the Dan grading. Dan grading is attractive to those who wish to shoot a ‘proper’ traditional bow (gakgung) with bamboo arrows. Achieving Dan 5 will certify you to use one of those, and will open the doors to serious team competitions.

Separate grading events take place once or twice a year, should you choose to get graded. Until then, you can – and many do – enjoy the modern traditional bow, shooting at most competitions as an individual, and in many instances at team events.

Based on my observations, team composition is divided by gender, although in intra- and inter-club or district events there are no restrictions against mixed-gender teams – it is the bow type that is more of a deciding factor.

Fifteen arrows

The standard shooting distance at all competitions is 145m, and the format follows the hit-and-miss principle of scoring. Typically, only three targets are utilised in competitions, each shooting line accommodating seven archers. So, there can be 21 archers on the line at one time. No warm-up ends are allowed, unless there is a pole-arrow (jusal) on the side of the range.

As an individual, you will shoot as part of the group of seven archers, or as part of five if you are a team member. Individual rounds are shot on qualification principle, whereas team events follow the principle of eliminations, based on the total amount of hits made by the team per round (kor. sun).

Each person on the line shoots one arrow at a time in order, from one to seven, repeating the order until all five arrows of the sun are shot. As an individual you will only shoot three sun (15 arrows) in the entire competition, a few more if you are also part of the team. If it sounds like a warm-up to you, then I can assure you, there is a lot more to it.

The Pace of Things

Pace and its unpredictability, in my opinion, is what is fascinating about the KTA competitions.

Even though you only shoot three rounds, you never really know when it is your time to shoot, so you must always be prepared. There is no room for error. You must engage in constant and daily practice to be able to show your best performance there and then when it is your turn. This is the spirit of the martial art of archery. It is like undergoing a four-year training period for those 10 to 12 seconds of an Olympic 100m.

Registration starts around 8am, and is typically open until midday. The first shooting detail starts at 8.30am. A long registration window means that you do not necessarily need to be an early bird. The number of competitors, the times of arrival and registration at which entrants sign on dictate the pace of the event.

Because the intervals are not strictly regulated or prescribed, as an individual you could spend on average about three hours waiting to shoot your 15 arrows. And even then, you do not get to shoot them all at once. Two events are certain to always run on time: the official 10am ceremony and the traditional Korean midday dinner.

The ceremony is attended by many senior officials and follows a prescribed routine. All the archers line up in groups according to their clubhouse membership, facing the seniors. Multiple speeches and addresses take place, the club representative reads the pledge of honest shooting, and the competition banner is handed down, symbolising the official opening of the competition. The archers listen to the Korean national anthem and return to shooting.

Doing the homework

Though at first the system seems confusing, I quickly got the hang of it. I had only had experience in shooting at one of the ranges in the programme of eight competitions before – my clubhouse. Aside from that, as a competitor I was experiencing everything for the very first time. However, I am very disciplined and focus purely on my form all the time.

I challenged myself to take part in all the competitions that I could, precisely because I really wanted to get the experience of the format and to look for opportunities for improvement as I went through this series of events. To help illustrate my point, I will explain how I used my observations of the first-time experience to progress, while shooting at the same range. Kwanakjeong is where I shot both my very first and the sixth competitions, with an interval of four weeks in between.

I had little practical understanding of the procedure when I first arrived. My clubmates and I went on to sign up at the registry window. There I was given a group number, telling me which detail of seven archers I will join. I was in group 14, and was assigned to shoot at target two, then three and, finally, one. Looking at the shooting list, you will notice there are time gaps between two details of archers. These are reserved for arrow collection.

You will also notice that gaps between one group’s movement can be closer, or further, meaning longer gaps between shooting. Additionally, there are no specific limits on the amount of time spent on one sun by an individual or the group – it is left to the judge’s discretion.

They are very sympathetic to individual shot cycle or equipment issues. On average it may take from five to 10 minutes to shoot one full sun by all seven archers on the line. Your actual shooting position (one to seven) is decided by lot during equipment inspection. Once your spot is assigned, you will shoot at the same spot on all three targets.

At my first competition, I didn’t score any points, shooting either little over or a little under. At that distance, margins for error are very slim, especially when you are not familiar with the wind and light conditions, and having 15 arrows, while changing position three times, is a challenge. But you must trust your form, otherwise your shooting will be a mess.

KTA clubhouses are all unique and set in different natural settings, presenting the archer with a unique challenge. On my second return to the venue for another leg of the district championships, Kwanakjeong, I used my experience and the notes and observations I had made first time round.

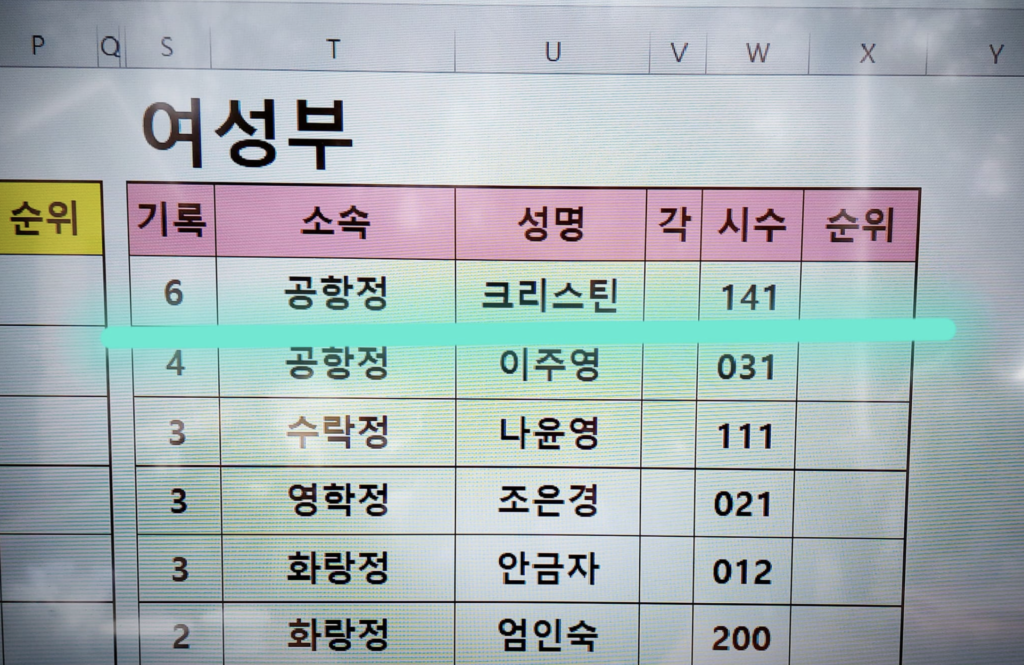

This time I produced my best performance: I led the scoreboard for females all day, almost shooting a molgi, or the perfect round, and hitting four of five on the second target, having not done that even in regular practice. I also won the achievement award medal and prize. I had done my homework and stayed true to my process at every event, increasing the number of hits as the events unfolded.

General Impressions

All the archers were individual, and I am beginning to see the influences of teachers on their students. There is no one way of shooting KTB – it is just as individual as any other bow, and many show both good and bad form, good and bad attitude. The difference is that you will see a lot more senior members on the shooting lines and, for the most part, the more senior and experienced (20-plus years shooting), the more accurate they were.

It is interesting to note that it was the senior archers and masters that came up to me pleasantly surprised, telling me that, “even though I looked like a westerner, I didn’t shoot like a westerner”. I received comments like, “Your form is perfect” and, “You look like a Korean warrior woman.” They liked the ease with which I controlled my 45lb bow and the smooth open style of follow-through I developed.

The comments I received were genuine – they were not trying to butter up ‘the foreigner’. Korean people, particularly seniors, are harsh judges and far from generous when it comes to compliments. They value discipline and respect.

Without sounding disrespectful to the Western students of KTA, I was gratified to hear I did not look like a westerner in my archery! My ultimate purpose is to continue to focus on the process, constantly developing, to chase that sense of effortlessness, balance and flow. Hitting the target is a bonus, but it is not the key intention of my practice. For me, KTA is primarily a martial art.

Final Note

I truly believe that in order to really understand something, you must experience it first-hand. To really understand and feel what it is like to compete in KTA in Korea, you really need to be in Korea. I just follow my path through hard work, discipline and dedication – everything will happen when it needs to happen. Where there is true passion, there can be no obstacles or excuses. You make your own ‘luck’.

it is both inspiring and informative to read your story here. Thank you

You are very kind, I appreciate it. Glad you enjoyed reading the piece and wish you all the best in your endeavours.