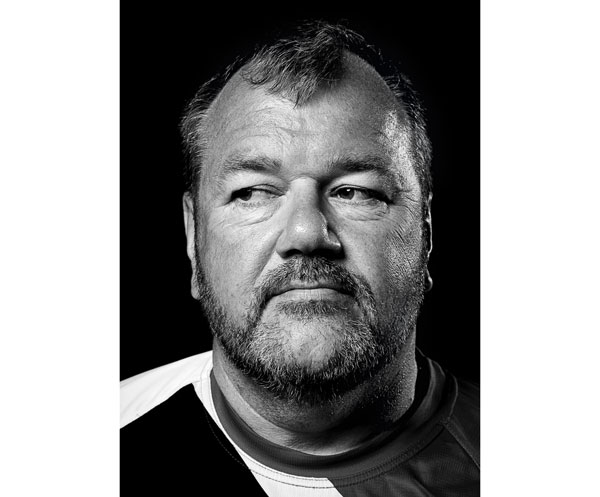

Tears and triumph: John Stubbs celebrates 20 years on Team GB in our exclusive interview, looking back at the highs, the lows, and the changes he’s seen

I was at selection shoots and I just didn’t know whether I was going to live for the next day. That’s how bad it was

John Stubbs is a man that doesn’t need much in the way of introduction in archery circles; a multiple Paralympic medallist, world champion, world record setter and stalwart of Team GB, he has seen and done it all. However, it might all never have happened, had archery not caught his eye one day as he left a sports centre after playing cricket. When the coach spotted him watching, John was invited to have a go, and the rest, as they say, is history.

“I just took to it like a duck takes to water when I tried it,” he says. He didn’t know then what archery would take him on to do, but says the desire to shoot and improve was there right from the very early days. “I realised I wanted to make something of archery,” he explains, “and it was the case that I was getting too good for just practicing at home, so then I went to a local archery cub. It was a bit of a chore, because where I chose to go and shoot wasn’t accessible, so I had access issues to overcome, but I didn’t look at it as though it was a struggle; I wanted to do archery.”

Getting more and more involved in the competitive side of archery, John started to hear more about the Paralympic movement and representing Archery GB. He got wind of the World Championships in 1997, and put his scores forward for selection – but missed the official cutoff date and thought he wouldn’t be able to go. Despite that, Archery GB invited him to Stoke Mandeville to a classification event. “The next thing I get a telephone call saying, ‘We’re sending the team over to Belgium, and it’s the World Indoors. We’d like you to go.’ I was like “Yeah!” – I bit their hand off.”

That Indoor World Championships turned out to be the first step on an international career that would span 20 years. John qualified fourth, and went on to win the silver medal, and he says, “That was the start of it then, and I just wanted to aspire to become something.” He was to find, however, that it wouldn’t all be plain sailing. The first World Championships he attended outdoors was in Christchurch, New Zealand, and, as he puts it, he “absolutely bombed out.”

“It was the worst weather we’d ever seen; we were actually shooting in hailstones. We were freezing, and I can remember I got knocked out, and I found this corner, and I just chucked myself out of my wheelchair and lent against the canvas side of the tent, and absolutely bawled my eyes out. It meant so much to me.”

He bounced back from the early disappointment, and after coming back from Madrid in 2003 with a silver medal was feeling much better about his shooting and much more comfortable with the international travel. “I was getting to go all over the world,” he says, “and when I had my road traffic accident I thought that was it in my life. I never knew that I’d go and see the world. I was on this fabulous journey and was doing something that I effectively fell in love with.”

“I’m always good on qualification, so I’d say the 720 round. That really puts me in a good frame of mind, if I’ve shot a good qualification round.”

At a later World Championships, he put his early experience to use and made sure the weather wasn’t going to get the better of him again. “Once I’d won my silver medal in 2003, we were working towards Massa in 2005, when, again, it absolutely threw it down. I shot immense in the qualification, then it came to the elimination round, and it was absolutely unbelievable weather, just torrential rain. Lo and behold I beat the favourite. My first three arrows of the start were the worst three arrows you could think of, I shot a six with my first arrow, and I was like, “Oh I can’t believe this,” but Alberto, fortunately, only shot an eight, and I’m like, “I’m still in this.” Then, it was a collective score over 12 arrows, and I remember slowly going through the shoot, clawing points back, and then it got to the final three arrows, and there was no way I was going to lose. I can actually remember people come up to me and say, “How did you shoot those arrows in the end?” and I just …” he shrugs and laughs. “They just went in the middle. I was on autopilot, and I got three Xs.

“I was world champion – I thought that was it, I thought that was the pinnacle of my career. And then we get wind in 2006 that the compound has been introduced in the Paralympics.”

A dream of his since he’d become disabled, all his focus turned towards the 2008 Games. As an inaugural event, no-one quite knew how it was going to go or how it would be received – but they needn’t have worried. “We were told, because it was the first time compound bows were going to be introduced into archery in a Paralympic Games, to just go and enjoy it.

“So we get to Beijing, and of course it was this iconic stadium. The vibes from the stadium just give you goosebumps. But the competition didn’t mean anything. I just went, and was going to enjoy it. Qualification day comes, and I’m just shooting my arrows the way I would normally do, not really paying any attention because I’m not one of these people that would score every arrow or want to see the score sheet – I’ve shot the arrows, you score them how you see them and let me sign it at the end of the shoot and I’ll take whatever you give me; I’m not going to question it because the people behind me will question it if it’s wrong. Well I came and signed it, and I’d not been seeing what had been happening on the television monitors, and everybody’s congratulating me and I’m signing away for 691, and it’s like, you just shot a Paralympic record. Well I had to do, because I was ranked first and it was the first time my bow had been introduced into the Games. So that was it, I was ranked first, and it meant I was going to shoot in the main stadium all through my competition.”

He says the announcement he’d be in the main stadium from the off for the eliminations didn’t change his expectations, or how he felt about the rest of the competition. “I was just there to enjoy it,” he explains, “and I did enjoy it. I can remember going in, first round, and there wasn’t many people in there, probably about 500 people. Which was still the biggest crowd I had ever shot to! Unfortunately, I was shooting against a good friend of mine, who had not ranked very well, and when I was shooting against him I only dropped three points. I shot a Paralympic record in my first round. And I don’t know why I did this, because I’m not that way inclined, but every time I hit a 10, I did an air punch – and I’m not that flamboyant, normally I would just get on with it, and move onto the next arrow – but I was giving this air punch and the Chinese crowd were loving it. Absolutely raising the roof to it. So the next day, it came to my next round, it had gone from 500 people to seven and a half thousand. I was like “OK – this is a completely different kettle of fish!”

“My best match ever – and I lost – was between me and Phillipe Horner, in the final of the 2011 Torino World Championships. I lost, and it was the best match ever, because it was 10 versus 10 versus 10 versus 10, and we were just slugging it out, the two of us, and nobody was giving an inch.”

How did he deal with that massive change in crowd and atmosphere?

“Because we were down here and the crowd was up there you didn’t really notice it; you knew that there was an atmosphere, but I was making an atmosphere every time I shot an arrow, and I continued on with doing this air punch, and I think I got known for it – if I didn’t do it, the crowd was like, waiting for me. And I just went through the competition, doing air punch after air punch, getting the crowd behind me. Lo and behold, finals day, and it’s my old adversary Alberto Simonelli. Before we were being introduced I’m peering around, as I think, “Wow, this is really something special, I’m in a Paralympic final. Worst outcome, I’m gonna go home with a silver medal from an event we were told to go and enjoy.”

I’m speaking to Alberto, and I’m like, “You alright mate?” and he was a quivering wreck. He just couldn’t handle it. Of course because I was highest ranked I opted to shoot first, and I think I shot 10-9-9 or something like that, and for me, all I was thinking about, was that first arrow: whatever you do, just put it in the gold, just settle your nerves down, put it in the gold. I think I shot another nine after that, and Alberto was all over the place … I’m two points up and not shot particularly well, then the last arrow of the three I shot a 10, air punch, crowd goes up. And I wasn’t playing games with him, it’s just what I was doing to get the crowd on my side. If you shot three 10s it’d come up on a big board, “10, 10, 10 Perfect!” I think I did that twice in the final. And I did it on the last end, and I don’t even know why, to this day, I actually did this, but I shot the last arrow, and knew I couldn’t be beaten, and I just looked up at everybody and shrugged my shoulders as if to say, you know, that’s all you can do. And then, reality hit home, what I’d actually achieved.”

The brilliance of the result – and the performance that had delivered it – seemed to seal John’s place in the record books. He says he was on cloud nine, spending the rest of his time in Beijing living as a champion and loving every minute. However, it wasn’t to last.

“But then it was like, where do you go from here? You’ve become Paralympic champion … what happens? You get home and it’s a big reality check. My bubble completely burst. I get home, the love of my life – we’d been married for 19 years – decided that that was it. She never even watched me in the final; she’d just fallen out of love with me.”

The aftermath of that took its toll, with a divorce that was far from straightforward, but the thought of a home Games in 2012 gave him something to work for and he came out the other side in 2010 and was really able to throw his all into that – only for everything to come crashing down again.

“It’s like, I want to go to this, I’ve got to go to this. So I went to 2012, and it just didn’t happen. I was reigning champion, practice was going phenomenal, and then … I can remember finishing practice on the Friday before elimination on the Saturday, and I picked my rucksack up – it just has my spotting scope and tripod in – and, “clunk”. I just dropped my rucksack straight away and was like, “Oh God, what was that?” I’d done something in my neck. I couldn’t feel anything in the fingers in my right hand and I’m like, “Oh my God, no.” I was thinking I’ve just twinged something, but I was sent straight in for an MRI scan, and they printed it off, showed it to the doctor – we had our own doctor – and she dragged me to one side and was like, “I don’t think we’re going to let you compete.” I was like, “Don’t be saying this Betty, I’m going to compete. By hook or by crook, I’ve trained for four years, I’m the reigning Paralympic champion, I’m going to compete. Even if I bomb out, I’m going

to compete.”

“The C5 disk in my neck had literally moved sideways and was compressing my ulna nerve, and that’s why I had the tingling sensation in my fingers. So I clearly knew I wasn’t going to be competitive. I went through the event, and it just didn’t happen. I felt so deflated. I felt as though I’d let everybody down. I was apologetic on Facebook, my family had made plans to come and watch me and I just felt as though I was a complete failure. And I’m like, I’m not going to finish there; I just can’t have that to be my end. I’m going to come back from this.

“My favourite opponent would have to be Alberto [Simonelli], because we’ve become very good friends, we totally respect each other, and we’re probably equal on head to head matches, so yeah I’d say Alberto.”

“So then it was 2013, the World Championships in Bangkok, and I’d already noticed that the final day shooting was going to be on my anniversary day of my accident. To anybody that’s had any major trauma it’s always a harrowing day, because it brings it all back. And I shot absolutely fantastic and I got to the finals day, and not only was I in the individual final, I was in the team final and the mixed team final. So I was involved in every major you could be involved in. I won the individual on basically the last arrow – I needed a 10 and I shot an X to win that.” He followed that up with another gold in the team event and mixed team silver, but it was all overshadowed by the new classification procedure put in place following the competition.

“That’s when Dani [Brown] de-classified. For me, that was as though you’d cut off my right arm. I’d lost my training companion from 2008, and I’m thinking, where do I go from here? You know, I’ve lost my training buddy – and she’d grown up with me. She was a child when she came on squad, and I’d nurtured her to become the athlete she became, and she was a phenomenal athlete, even in the able-bodied world. So I’m trying to celebrate my success, but on the back of that you’ve just had someone de-classify, and it’s hard to be happy because someone’s suffering as much as they were. So I was extremely proud of myself, but I couldn’t show that true emotion because Dani had lost everything.

“2015, we were in Germany – I wasn’t particularly in a good place, psychologically, because of one thing or another, but I went there, and I went there thinking, “Well, I’m current world champion, I want to defend that.” And this is where Alberto got his own back on me, because he beat me in the quarter-final, and he knew then, that by beating me, that was his competition. Unfortunately he came second again!

“I came back with a silver and a bronze, so I should be proud. But I’m not, because I’m a winner and getting a silver and a bronze is you’re best loser and second-best loser. And then it was all working towards Rio.”

John is open about admitting the toll everything had taken; from the Germany World Championships onwards, he was struggling, and it all came to a head in the summer of 2016. “2016 was an absolute pig of a year. I was not in the best place, and I’m not embarrassed to say that I wasn’t – I clearly wasn’t. I was at selection shoots and I just didn’t know whether I was going to live for the next day. That’s how bad it was. It got to the stage where I was just going along with it … psychologically I was absolutely shot. It got to one selection shoot where I think I broke down in tears in front of my whole team, and with that I just decided that’s it, I’m never going to shoot again. I left my kit, just got in my car; I was driving like an absolute maniac, and it was only one manoeuver that was like a lightbulb moment. It was when I went to overtake two cars on a bend that I shouldn’t have done, and a motorcyclist was coming in the opposite direction. It was then that I realised what I was doing, and it was then that I’m like, “I need to go and get some assistance here.””

“Archery’s just a sport where you compete against yourself. It can give you that inner confidence to realise that, you might have some form of disability or ailment or whatever, but it doesn’t stop you picking up your bow and competing against yourself.”

With the help of his girlfriend at the time, John received some medical attention, which helped. He slowly came back to it, and says, “I’m not saying it’s fashionable if you’re suffering with depression because having been there it’s absolutely horrendous, but it’s more in the public eye now. It’s out there that, even people in the top of the sport, how they’ve had to endure it and how they’ve overcome it. And how they hide the fact,” he says, reflectively. “You know, we put on this hard exterior to the world, “I’m John Stubbs and I can shoot a good arrow whenever it matters” – but I couldn’t, I just couldn’t bring myself to shoot.

“But I knew that I wanted to go to Rio. After the first selection shoot, I think I was in first place but only just. Then it came to the next selection process and it was all head-to-head matches – I don’t even think I won one. I went from being first to third, and I’m thinking I’m not going to go, here. First two past the post went, and third person was head coach’s discretion. I just resigned myself to not going. And it was only when I got that telephone call to say, “You’re going,” that … it was a big sigh of relief. And then in a short period of time, you’re trying to get some form back. I didn’t particularly shoot well in Rio, and in fact I only got the nod off the head coach when it came down the mixed team event – which I won the silver medal in – as I found out recently, because I had the experience and I was more of a presence on the shooting line than Nathan [Macqueen] was going to be. But I felt terrible for Nathan because I’d taken one of his opportunities to medal. I was trying to console him, knowing that I’ve taken his place. But when you look back, you’re competing for your individual self, but you’re competing for the programme as well, and if I do well, individually or as a team, the programme benefits by it. Fortunately me and Jodie came back with a silver medal, and that’s why I’m here now.”

It’s an incredible career trajectory, taking in the heights at the pinnacle of the sport as well as the lows, so what’s the biggest thing John has seen change in the sport over that time? “I’ve got to say it’s money; it’s the lottery. It’s been good, and it’s been bad. You’ve got the older elements on the team that have had to go out there and fund it themselves, and I can remember I was working, sacrificing holidays, just for my archery, and from 1997 to 2006 I didn’t receive any funding – I funded it myself. Whereas now, with the lottery, it enables athletes to effectively not need to work. So it’s putting people in a false light, if you like; they’re not growing up.”

His experience comes to bear on other aspects of archery as well, as he often finds himself in an unofficial mentor role to the younger and newer members of the squad. He is and always has been generous with advice – even to his competitors – saying, “At the end of the day I want them to be in their best place if I’m going to beat them. I want to be on a level playing field. But I never came into sport to be a role model, and I hate being given that title, because with that comes that responsibility, and it’s as though you can’t let your hair down and enjoy yourself. Yeah I’m very serious on the shooting line, but it’s only for that split second or those four minutes. But I’m a bit of a joker away from it, and I don’t feel as though I can be that when I’m a role model, so that sort of curtails that element of it. I definitely feel as though I’m a mentor – I do a lot of things voluntarily, I don’t expect any payment for it, and I’m very fortunate that I’ve been able to win this array of medals, so I’ll go and do talks and never charge for them because it’s my way of giving something back. I think it’s why I was bestowed, in 2006, with my MBE. I got that before I won any Paralympic medal, because I gave so much back over that short duration of time,” he says, adding, “You know, I’ve never received any accolade for what I’ve achieved in archery, which is bizarre, but that’s just the way it is.”

A career in medals

Middle:

– MBE 2006

Clockwise from top left:

– World Championships 2005

– World Championships 2013

– Paralympic Games 2008

– Paralympic Games 2016

The fact he’s been decorated for his voluntary work rather than his medals does seem quite strange in the light of the number he’s won, but he says it’s indicative of the community side of archery, rather than the competitive element. “To me, the archery community – and especially in Great Britain – becomes an extension of your family,” he explains. “I think we have something like 45,000 members, of which you probably see 1,200 competitive archers, all the rest are recreational. And you might stumble across these over the course of the season, but they all know you. Not only that, but we get a reputation for not just being a para-archer, but being an archer full stop. Disability doesn’t come into it. I remember in 2010, challenging for the Commonwealth Games. There was two disabled archers on that line, me and Dani, and I was reserve on something like 0.2 of a point over three selection shoots. That’s how close it was. That’s just built the respect that we as disabled archers get from the whole of the

archery community.”

John likes the fact that, at a domestic level, there isn’t a split between para-archers and able bodied archers. “If you want to be the best, you’ve got to compete against the best,” he says, “and we’re very fortunate in Britain that we do have competitive world-class archers, and we have some of the best facilities. Why does disability have to come into question? It doesn’t. I remember last year or the year before, I was runner-up in the Masters. So, it’s taken on merit, and able-bodied people realise they’ve got a challenge if John Stubbs or any of the squad archers roll up onto that shooting line. But we’ve got that added bonus of beating an able-bodied person. We’re living life as a disabled person, in a society that doesn’t really take or accept disabled people, so to be on a level playing field and competing at the highest level in the sport it’s great testimony to us to

pursue that.”

Reflecting on everything he’s seen and done, everything he’s achieved and everywhere he’s been, John seems as though he can’t quite believe it all. To be suddenly made disabled in your early twenties was a hard blow, as he acknowledges; “I just thought my life was over.” That said, he calls it ‘the first day of the rest of my life’, adding, “I would never have taken up archery as an able bodied person, and look what it’s given me! I’m so thankful for finding the sport. I’ve been to places, seen things, met people, received things I would have only ever dreamt of. And to think, I’ve become somebody – I would never have dreamt of this, I’m doing things that celebrities do, and I wouldn’t look on myself as a celebrity in any shape or way or form to be honest, but I’m living a fantastic lifestyle. And it’s mad.”

Mad it may be – but it’s not over yet. John reveals there is one last thing he wants to tick off his to-do list before retiring. “At the start of my career I set myself a few personal goals, that I want to achieve, and I’ve done everything bar one.

“I’ve never divulged what it was. I don’t mind divulging what it is, but it’s to basically to be the first Paralympic archer to shoot 1400 on a 1440 round. If it was to all end, and I would have achieved that, I would retire gracefully. If it doesn’t happen it doesn’t happen, because to do something like that you need everything to be in your favour. I’m not saying it can’t be done, but everything’s got to be there, just right, and you’ve got to be on top form.

“1383 is my PB, but to make those extra 17 points, there’s not much room for error. I’m not saying never, but where we as wheelchair archers lose the points is at the further distances, 90 metres, because the elevation is immense to us guys. I can lose 25 points just on 90 metres; it doesn’t give me much to work with then.

“So when that happens, you might see John Stubbs retire – even before a World Championships or whatever, because that’s everything ticked off then. But never say never.”

This article originally appeared in the issue 118 of Bow International magazine. For more great content like this, subscribe today at our secure online store www.myfavouritemagazines.co.uk