In his fifth and final instalment on building the perfect set of arrows, Adrian Tippins explains how to weight match you arrows – and why it’s worthwhile doing. This is part of a series of posts, for part 1 of this series click here.

You should always assess the shafts first as the results will dictate how to proceed with the points

Not all arrows are created equal. In this fifth and final part of this series on arrow-building we’ll be taking a look at what can be done to build a set of arrows that are a cut above the rest and fit for use on the international stage. The main objective we have is to build a set of arrows that are alike to the smallest possible tolerance. The benchmark that I like to set for competition arrows is to get them identical to one tenth of one grain. If this can be achieved the archer will experience really tight groups when coupled with consistent shooting. In previous instalments of this feature I have extolled the virtues of being obsessively consistent and precise with everything you do and, more importantly, everything you use. This is where your attention to detail – or lack of it – will really show up.

Spine testing is one way of matching your arrows, but for non-wooden shafts weight matching is often a better bet

We’ll refer to this quest for weight perfection as “weight matching”. Sometimes getting great results is easy, and sometimes it’s not. This is down to the fact that the weight tolerances of different components differ. Normally, the top end AC competition shafts have a tolerance of +/- 0.5 grains. Full carbon arrows tend to have a tolerance of +/- 1.0 grains. Therefore, it’s easy for one to assume that on paper it’s easier to get a tighter set of arrows from the AC variants but this isn’t the case. No matter what arrows are being used, the fletcher is at the mercy of the components supplied. A great set of arrows requires that the shafts have been carefully manufactured and finely sorted into batches with super fine tolerances. Easton actually print their sorting weight code on the shafts, which appears as the C number along with the rest of the arrow information. Shafts within the same spine have a microscopic weight differences due to manufacturing tooling and material variances. This is also true of all arrow components including points, pins, nocks and vanes.

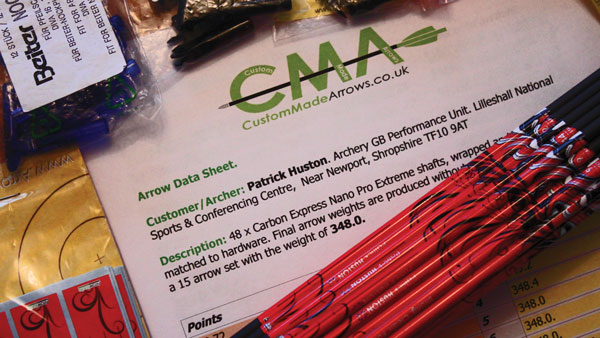

CMA customers can choose to have their arrow data provided to them in a spreadsheet

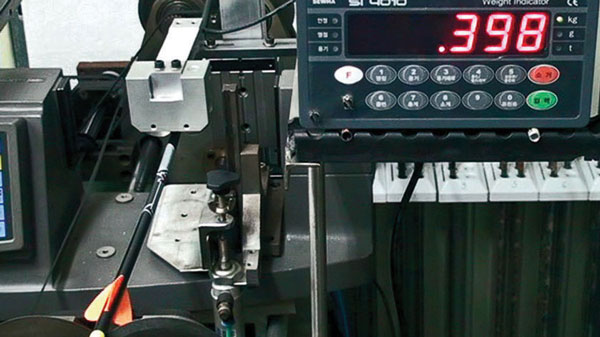

The weight matching requires that the arrows can be individually identified. Hopefully you will have already applied a numbered wrap to the arrow prior to fletching. To start the process, I fully complete the fletching process so that I have finished arrows that don’t as yet have any points installed. The fletched shafts are then weighed on precision scales that can weigh down to one hundredth of a grain. The weight values are then listed in a spreadsheet alongside the associated shaft number. The points are then weighed and listed in a similar fashion and a number is assigned to each point. The parts are then cross matched to each other. For example, the lightest point would be assigned to the heaviest shaft. This process is repeated until all the parts are married up.

If you are using break-off points that have been manually broken down to achieve a desired weight setting you will probably experience a slightly wider weight span across the dozen than those that are inserted whole. This is entirely natural as the sections don’t always break off in the same place, leaving tangs of different length. This is not always a bad thing as you may well need a larger weight span of points to compensate for wider weight discrepancies in the fletched shafts. If your fletched shafts have a really small span across the set you may wish to file the tangs to make the points more consistent, thus closing the weight span. Therefore you should always assess the shafts first as the results will dictate how to proceed with the points.

Trust in your equipment is vital when the competition is so tight

Once you’ve matched up your arrows and components, the points are carefully glued into the associated shafts. It’s this stage that’s really hard to control as it’s difficult to control the amount of hotmelt glue that goes on on to each point. It takes skill and a lot of practice. Even the smallest variance can throw figures out. There is an option to use a more easily applied and metered adhesive such as Insert Iron, however, although this option is super strong and impact resistant, it makes the points very difficult to remove should the need arise.

Once the points have fully cured the total arrow is then weighed again to one tenth of one grain and the value recorded against the correct number in the spreadsheet. It’s really important that you keep this record of the set. We provide this spreadsheet to CMA customers so they know which arrows in the dozen are most alike so they can make their primary shooting selection. Should an arrow get damaged it’s also really handy to know which of the reserve numbers are most alike to the primary group. We’ve made weight matching a primary focus for our competition arrows. It’s reported from the highest of levels to have far more of an impact on grouping than other methods such as spine testing, which we now take a look at.

Adrian made up a set of arrows for Paralympian Nathan MacQueen that were identical to one tenth of a grain

Although it’s now been superseded by weight matching, spine testing is still something a lot of archers like to indulge in. This practice is still very important for those shooting wooden arrows as wood grain is inconsistent, giving different static spine readings depending on which way it’s flexed. This is the process of finding which side of the shaft is the stiffest or weakest. Arrows do have a spine even if it is a microscopic amount. This has some effect on how the arrow behaves when shot and its dynamic aspects in the archer’s paradox. The theory is that if vanes are all placed consistently in relation to the spine of the arrow each one will have the same rotational properties and can thus help with more consistent grouping. The best way to find out which side is which is to place the arrow on a digital spine tester and take readings on various rotations. I have heard of some people rotating nocks in bare shafts to examine results and some floating shafts in a bath in the hope that the heavy side will face downwards and be identified.

When there’s just a few points between getting a medal or not, every arrow – and the archer’s confidence in it – counts

My own personal and professional experiences have shown weight matching to be far more critical than spine test vane positioning. A case in point are the arrows made for one of our Paralympians to compete with at Rio 2016. I didn’t do any spine testing on them, but they were made identical to within one tenth of one grain. Everything about them was perfect – vane positioning, vane placement height, glue levels, relationship to wrap seam… everything was identical. When tested on a Hooter Shooter at 50m, the dozen arrows grouped in the space of a 10 pence piece.

For me, this was a definitive test and showed the results of painstakingly obsessive assembly procedures. Archery is a sport that’s very tight at the top. Placing for a medal or not is usually the difference of just a few points. Therefore the difference between shooters is normally mental. As the mental side of the sport is so important shooters need to go into tournaments with totally clear minds knowing their kit is world-class and the best it can be. Even though something may not show up any tangible or measurable results, it’s still worth doing it if it takes even the smallest seed of doubt away from a shooter, allowing them to fully relax and just shoot.

This article originally appeared in the issue 120 of Bow International magazine. For more great content like this, subscribe today at our secure online store www.myfavouritemagazines.co.uk