Jan H. Sachers this time Jan H. Sachers delves into the contents of Asham’s archery manual

Roger Ascham’s Toxophilus, first published in 1545, is considered the oldest written introduction in Europe on how to shoot with bow and arrow. But it was not the sole achievement of its author, who himself had practised archery since childhood, to share his passion and experience with his readers, nor to instruct them in the discipline. His ‘School of Shooting’ is a complex work of literature, demonstrating Ascham’s intellectual and linguistic capabilities, and reflecting his ambitions, morality, and views on society and education.

In the mid-sixteenth century, Latin still predominated amongst scholars as the language for intellectual discourse, written and spoken, the vocabulary and grammar of English being considered too crude a tool for the subtleties of academic and philosophical thought. Given the long tradition of precise classical terminology, replacing it with an English equivalent was never going to be easy. Hence Ascham was not exaggerating when he wrote in the dedication to King Henry VIII, “to haue vvritten this boke either in latin or Greke […] had bene more easier and fit for mi trade in study”. But instead, he had decided to write about “this Englishe matter in the Englishe tongue, for Englishe men”, because he considered it to be “a thinge Honeste for me to vvrite, pleafaunt for some to rede, and profitable for manie to folovv”. (p. 14).

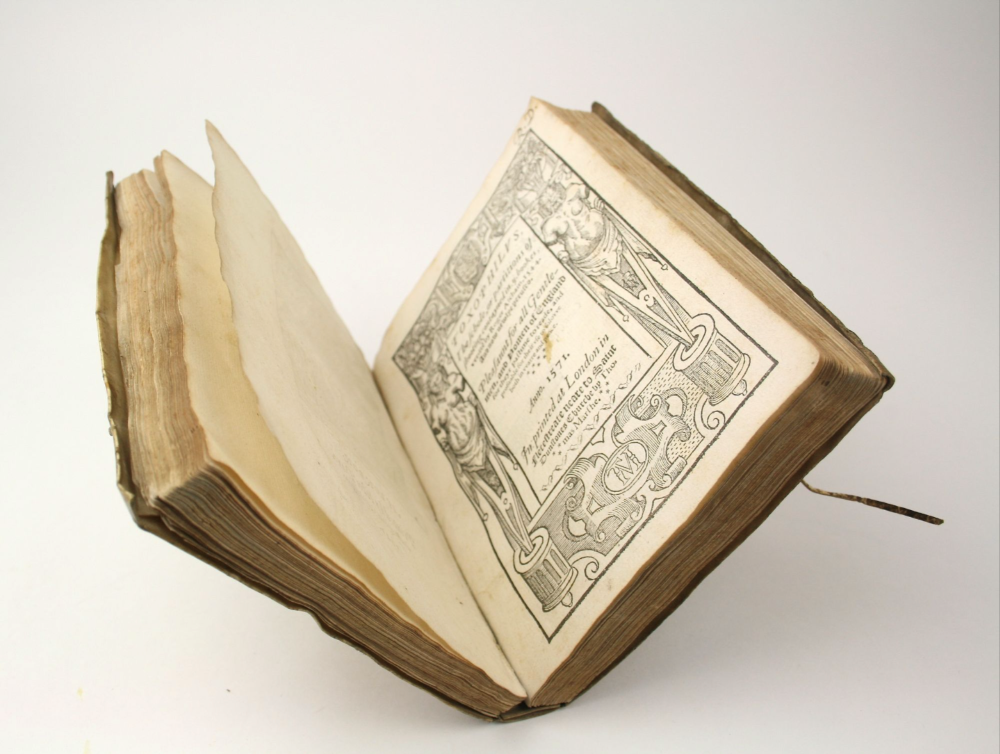

THE GUIDE” AND SHOULD THEREFORE REMAIN FIXED ON THE TARGET, NOT WANDER OFF TO THE ARROW, THE SURROUNDINGS, OR ANYTHING ELSE (P. 163). © LIBER ANTIQUUS EARLY BOOKS & MANUSCRIPTS

Value and Benefits of Archery

Still, Roger Ascham took quite a risk with his endeavour. His enemies and competitors had long belittled him because, even after so many years at university, he had failed to produce any research or publication worthy of a mention, something which they partly blamed on his excessive passion for archery. So, attempting to write a book in the vulgar tongue about this very subject does not at first sight appear the smartest move. However, the gamble paid off. He countered accusations of lacking intellectual substance not only through the content of his book, but also by its formal structure, an artfully crafted two-part Platonic dialogue between Philologus (lover of words), and Toxophilus (lover of the bow).

After the dedication and prologue, Ascham‚ or his alter ego, spends the next, roughly, 80 pages praising the many virtues and benefits of archery, and pointing out why it is not only an honest pastime fit for “princes and greate men”, but also for “scholers and studentes”. He argues that, as an antidote to intellectual work in a seated position, the practice of archery, standing upright and straight in fresh air, is highly recommended, since it brings the humours into balance and into motion, and sharpens both the senses and the mind.

To this claim is added a number of moral arguments. While associated with idleness, betting, gambling, and other vices by its enemies, archery could not be further removed from these, since it had two tutors, “the one called Day light, ye other Open place, whyche ii. keepe shooting from euyl companye”. (p. 52).

Archery is a virtuous pastime, because “companions of shooting, be prouidens, good heed giuing, true meatinge, honest comparison, whyche thinges agree with vertue very well” (p. 53).

Providence, mindfulness, precision, and honest comparison are also, as he points out elsewhere, worthwhile characteristics for public servants, diplomats, and other public figures. Hence archery not only advances the beneficial development of the individual, but also the moral and ethical constitution of society and state, a primary requirement of contemporary humanistic ideas.

Ascham also references authorities like Plato and Aristotle, who also praised archery’s positive contributions to society, and he mentions numerous bow-wielding heroes of antiquity as role models. Moreover, even “the learned Bishops” were known for their fondness of archery. This probably refers, amongst others, to Hugh Latimer (1485/92-1555) who was indeed a passionate archer, and often used archery metaphors in his sermons and writings, thus making him a highly respected and revered ally of Ascham in his intellectual crusade.

No apology for the bow and arrow would be complete without accounts of its military utility. Ascham rehearses these at great length, offering examples from antiquity to his own age, and paying special homage to the English archers and their victories over the Welsh, the Scots, and the French. He mentions Crécy, Poitiers, and Agincourt, and stresses the importance the medieval English commanders attached to large numbers of well-trained, reliable, and disciplined archers.

Ascham also knows why English archers were so numerous, and so effective in battle:

“England may be thought very frutefull and apt to brynge oute shooters, where children euen from the cradell, loue it: and yong men without any teaching so diligentlye use it.” (p. 93). But the once obligatory practice on Sundays and holidays had since fallen into neglect: “Learnyng to shoote is lytle regarded in England, for this consideration, bycause men be so apte by nature, they haue a greate redy forwardnesse and wil to use it, al though no man teaches them, al thoughe no man byd them […] and shoote they ill, shote they well, greate hede they take not”. (p. 95).

Effectiveness in war can only be achieved through regular practice in peace and thus the ‘Schole of Shootinge’ can also be considered an appeal for the military training of the young. Ascham explicitly applauds the repeated efforts of English monarchs to make archery a mandatory pastime, banning other sports and games, as Henry VIII himself had reiterated only shortly before. In contrast to other authors, however, who polemicized against the abolition of the bow as a weapon of war, and often used his arguments almost verbatim, Roger Ascham did in fact also recognise the importance of firearms in conflict.

Ascham makes use of a number of figures of speech and stylistic devices, following the rules of good rhetoric as laid out by authors like Cicero. He also embellishes his discourse with similes and quotations from classical literature which leave no doubt about the breadth of his reading, his erudition, and his scholarship.

The impact his work had on the development of the English language is testified by the fact that numerous words used by Roger Ascham for the first time appear in the Oxford English Dictionary. The first part of Toxophilus in particular shows him as a linguistic innovator, an erudite and competent author, and a shrewd and surprisingly modern teacher, driven by humanistic educational ideals which give equal weight to the welfare of the individual and of society as a whole. Aside from these scholarly and philosophical qualities, he was also an entertaining storyteller and a great patriot.

The Point and Accessories of Archery

After Toxophilus,with sound and clever reasoning, managed to convince Philologus of the values and benefits of archery, Philologus begs to learn more about its practice. So begins the second part of the book, which possesses a systematic didactic structure in which each element follows logically from the one before, as shown in a graphical representation in the table of contents.

The first question is, “What is the cheyfe poynte in shootinge […]?”, to which Toxophilus gives a simple, yet truthful, answer: “To hyt the marke.” (p. 106). However, hitting the mark, and doing so consistently, depends on various factors which Ascham explains in great detail, beginning with the equipment.

He does not consider a bracer or wrist guard necessary, but if one is worn, it should have no nails, buckles, or aglets to interfere with the string, but be fastened to the arms with laces.

A “shootinge gloue” is worn to protect the fingers drawing the string and should be made of fine leather lined with velvet, so the leather will not harden when in contact with sweat. To keep the fingers from pinching the nock too tightly, Ascham recommends sewing either a feather quill between leather and lining, or a piece of rolled leather to the outside of the finger. “The shootyng gloue hath a purse whych shall serue to put fine linen cloth and wax in, twoo necessary thynges for a shooter.” (p. 110).

The string should not be made by the bowyer, the fletcher, nor the archer himself, but by “honest stringers”, because “ill stringe breke the many a good bowe, nor no other thynge half so many”. (p. 110). Whether it be made “of good hempe as they do now a dayes, or of flaxe or of silke” is left for the craftsman to decide. It is more important for the string to be of the right length and thickness, to fit the smoothly rounded nocks well, and to be replaced when it shows signs of wear and tear.

When dealing with the bow Toxophilus first points out that “[d]yuers countryes and tymes haue vsed alwayes dyuers bowes, and of dyuers fashions.” (p. 113). He mentions “horne bowes”, and bows of “brasse, yron or style”, which are no good, as well as palmwood, and reed. “As for brasell, Elme, Wych, and Assche, experience doth proue them to be but meane for bowes”, so according to Ascham or his alter ego, “a bowe of Ewe must be hadde for perfecte shootinge at the prickes”, or in fact rather three or four, just in case.

He then goes to great lengths to explain how to recognise an honest bowyer and a good bow. For transport he recommends a “bowecase” made of leather, and for storage a wooden case placed “not to nere a stone wall, for that wyll make hym moyst and weke, nor yet to nere any fier for that wyll make him shorte and brittle.” (p. 119). Wooden cabinets in which longbows could be stored upright were very common up to the 19th century and were known as ‘Aschams’.

The bow should be rubbed down daily with a waxed cloth made of wool or hair.

Of the fifteen different types of woods that had been used for arrow shafts, only “Birche, Hardbeme, some Ooke, and some Asshe” are considered suitable for war arrows, “and not […] Aspe, as they be now a days.” (p. 126). The arrows should match the bow and the archer, in respect to their length, weight, and balance – at no point does Ascham mention arrow stiffness or spine.

Shafts tapering toward the nock are called “bobtayles” and suited for those “whiche shote vnder hand”, meaning at greater distance, while he “whych shoteth right afore him” needs breasted or barrelled arrows.

Nocks can be fashioned in different ways, but “the shalow and rounde nocke” best helps a clean release. Splicing in a fore-shaft, or a nock end, of Brazil or Holly wood can be used to make the arrow heavier and to correct its balance, but Toxophilus considers this practice “more costlye than nedefull.” (p. 128).

Only goose feathers are suitable for fletching, and they should be cut either “swyne backed” or “saddle backed”, although “al maner of triangle” is also acceptable (p. 133). Most important though, the fletching needs to match the diameter of the shaft, the weight of the arrow, the manner of shooting, the weather, and so on. Ascham describes the choice of good feathers and their attachment to the shaft in great detail, so this may be the only craft he didn’t leave entirely to the professionals, but trusted the archer himself to accomplish.

Arrowheads like the “brode arrowe or swalowe tayle”, the “forke head”, or the “bodkin” are suited for hunting and war, but not for target practice, or “pryckyng”. Ascham describes three different types of points, with the terms “sharpe” and “blont” apparently referring to the shape of the socket. The best ones are called high ridged, creased, shouldered, or “syluer spone heades, for a certayne lykenesse that suche heades haue wyth the knob ende of some sylver spones.” (p. 138). These silver spoon points had a rounded shoulder which helped with a constant draw length when it touched the forefinger of the bow hand.

Form and Practice of Archery

Finally, after introducing all the necessary equipment, its history and mentions in classical literature, Toxophilus deals with the shooting itself. “[T]he best shootynge, is always the moost cumlye shootynge”, and “comely shooting” is made up of five components, namely “standynge, nockynge, drawynge, howldynge and lowsynge” (p. 144). Then follows a long list of mistakes that Ascham has witnessed in other archers, avoiding which shall more or less automatically result in correct technique.

The stance is upright, (but not too straight), stable, and balanced. The bow is held horizontally, the arrow placed above the hand with the cock feather up, and slid onto the string, “neyther to hye nor to lowe” – the (string) nocking point being a later invention. Then the arrow should be drawn to the ear, until the index finger of the bow hand feels the shoulder of the point. “Holdynge must not be longe, for it bothe putteth a bowe in ieopardy, and also marreth a mans shoote”. The release should then be “quycke and hard”, so that it happens naturally, but also “softe and gentle”, so the arrow can fly straight and true (p.148f.)

Other factors that can have an impact on the shot are wind and weather, about which Ascham has a lot to say, the target, and the archer’s state of mind. A good shooter should be courageous, calm, and suppress his emotions, particularly his anger.

Toxophilus describes various aiming methods, but dismisses them all, because “[t]he eye is the guide” and should therefore remain fixed on the target, not wander off to the arrow, the surroundings, or anything else (p. 163). In order to correct such bad habits, he recommends shooting at two lights in the dark, which forces the archer to focus solely on his mark, and nothing else.

Ascham’s instructions on proper shooting make up a rather short section of his book, but they are complete, and give sound advice still worth adhering to today when shooting with a traditional longbow. Later authors had little to add, so they often simply summarised Ascham’s teachings in their own words. Horace T. Ford, as late as 1856, was the first to introduce the new method of anchoring under the chin, and thus revolutionised target shooting with his book Archery, its Theory and Practice.

Roger Ascham could not foresee the long-lasting success and appreciation of his book in re Sagittaria, nor could he enjoy it long. But even in his lifetime it was widely circulated, held in high esteem, reprinted first in 1571 shortly after his death, and then again eighteen years later. Still, the bow-loving scholar had good reasons to be content: he had proven that even a seemingly banal and common activity like archery can be the subject of academic discourse, and that his love for it did not get in the way of his learning, or hinder his intellectual capabilities. Not least, he had helped establish the English language as a medium fit for dealing with complex matters, following Aristotle’s advice “to speake as the common people do, to thinke as wise men do” (p. 18).

Ascham may have derived some satisfaction from these accomplishments, but his motivation to write his book in the first place had been a lot more down to earth: patronage and financial security were the marks he had been aiming at. He had dedicated his work to King Henry VIII, himself a passionate archer, and sent a copy to the privy council, where it was well received, winning him an audience with the king, and an annual royal stipend of £10, later doubled to £20 by Queen Mary I.

Such mundane, but tangible benefits were without doubt more valuable to a poor scholar with a growing family, than everlasting glory, and pride of place in any serious archery library – accolades which belongs to Roger Ascham’s ’Toxophilus’ nevertheless.

References

Roger Ascham: Toxophilus, The Schole of Shootinge, London 1545.

Lawrence V. Ryan: Roger Ascham, Stanford 1963.

Harald Schröter: Roger Ascham. Toxophilus, The Schole of Shooting, St. Augustin 1983.

’Toxophilus’ online: https://archive.org/details/RogerAschamToxophilus1545/

Image supplied © Liber Antiquus Early Books & Manuscripts