Bow investigates the extraordinary world of flight archery, the art of shooting an arrow as far as possible.

I’m on an airfield. East Leeds Airport, the former RAF Church Fenton, and one of just a tiny handful of places in the UK where you can do one particular, rarified version of our sport.

Much of a flight archery shoot will be familiar to most of you used to competing in the UK: the line, the details, the hunting for arrows, the tents, and even the drizzle. But the rest of it really is nothing like anything else; a monomaniacal quest to go higher and further than someone has gone before you.

Today here in Leeds is a de facto national championships in all but official name; all the associated regional shoots have been cancelled, and most clout shoots as well.

Tony Bakes, the organiser of this meet and a longtime ambassador for the sport, has a gleam in his eye when he talks about flight. “Bear in mind a lot of archers are very ignorant about what their equipment can actually do. This is one of the few times you can actually find that out. And then you can understand why we take safety that seriously.”

Shooting arrows immense distances is a key part of the history of the bow; from the mounted archers of Genghis Khan to the longbow’s heyday in medieval Europe, archery was long about distance. Flight has been going on for centuries; as a sport, its heyday was perhaps in America in the second half of the 20th century. Its technical innovations, such as using fibreglass and carbon fibre, quickly spread to other parts of the archery universe.

It has been frequently and confidently described as ‘the Formula One of the sport’. It’s perhaps closer to the Formula One of the 1970s than now; with privateers and experimenters pushing boundaries and limits.

You can’t buy unlimited flight bows off the shelf. This is a sport for the builders and the engineers, the tweakers and the obsessives. It’s also one of the few spheres of archery where at least a certain amount of brute strength becomes an advantage.

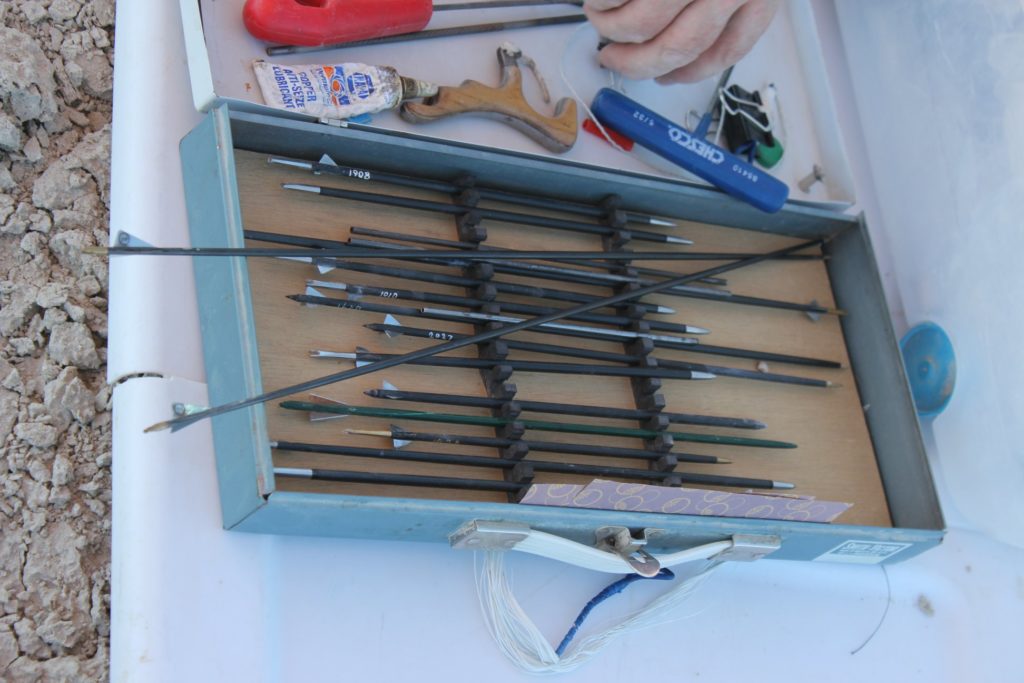

A flight shoot consists of a weigh-in, followed by four ends of six arrows, with hunting and marking out your arrows after each end. Archers carry marker flags, usually in bright, visible colours, to see where their best shots have landed. With the time taken for hunting and marking, the four ends can often take the best part of a day; it can be a long journey to shoot just two dozen.

The arrows land stuck in the ground at about 60 degrees, they will be straighter with the wind against you and flatter with the wind behind you. Each archer and class’s best shot is marked at the end; using an arrangement of prism and plumb bob, each shot is precisely measured. “I’m measuring in yards. It’s a UK record status shoot and I don’t think there will be many records broken today so it holds better in imperial. But when it’s a world record event we will set up in metres and convert at the end when we get all the results.” says Tony.

The field today is marked out to 900 yards, with stakes and reference markers for distance. “There’s a runway after that, then we’ve got the option after the runway of another 500 metres on top. Tony Osborn here is the only person in the UK to have shot beyond the runway. That was with a specialist compound flight bow, and he did 1050 metres. Extraordinary. Nowadays the fastest compounds can regularly exceed the seven, eight, or nine hundred yard mark. When I started shooting flight in 1976 anything over about 800 yards was considered exceptional. Now even target recurve bows can push things close to 600 yards or so.”

The multitude of bow classes available, usually at three weights: 35lb, 60lb, and unlimited, and the more relaxed time constraints mean that many serious archers often shoot multiple classes at the same event, and often with the same bow; compounds can be redialled in with different weights, and recurve flight and target recurve bows can be tweaked differently according to the various rules.

But you’re entering another world. In the target recurve class, stabilisers and sights are usually dispensed with, and you have to use off-the-shelf arrows, vanes and points – although you are allowed to machine these in various ways; ground out points and shaved off fletches are universal. (Three fletches are required.) Stabilisers, sights, and clickers are dispensed with, and bow weights are measured at the point where the arrow falls off the rest. Specialist flight recurves can be shoot-thru or many other designs, although mechanical releases are not allowed. Tabs are less common, and many flight archers shoot with a simple strip of leather.

The basic goals across the board are trying to get the arrows as light and aerodynamic as possible, and as much power, speed and cast out of the bow as possible. Many of the usual concerns of target archery, such as stability and consistency, are forgotten. Strings are reduced to a handful of strands, just above the breaking strain. New geometries are tested, sometimes to destruction. Limbs are mutilated and shortened. (Legend has it that if you try to talk to a well-known UK manufacturer about obtaining a pair of limbs for flight archery, they put the phone down on you.) Explosions on the line are not unknown.

I speak to Paul Smith, who has the technical bent of many top flight archers; he has an extensive background in automotive engineering. Paul’s custom-made flight recurve is made from plate aluminium with 3D printed components, and short Win & Win limbs. Paul designed the riser and the geometry himself specifically around those limbs and his own body frame, in order to produce a bow on the 50lb limit with minimal stacking.

Frequently, standard target arrows like ACEs or X10s are used, and then customised with extra light points and tiny fletchings. Today, competing in two recurve classes, Paul is using 3D printed fletchings, attached to a hollow carbon tube, that go into the machined metal nocks, that are then bonded onto the carbon, with the whole thing hot melted into the arrow – a further customised Easton X10.

“You’re looking at a very light weight compared to a target arrow.” he said. “You could be down to 10 or 12 grains in total for the point. You’re ultimately trying to elude gravity and you don’t want these things to dip in too quickly, but you want to give these things as much energy as possible, and if it’s got mass, it’s got that inertia down the range. In terms of total mass, it depends on the characteristics of the bow. I’m using Border limbs on my other, 35lb recurve, and I’ve got an extra short limb on a 25″ riser.”

“You’re always trying to optimise, within that package, whatever will give you the most speed, and the reason for these little tiny fletches is so they don’t get ripped to shreds when they leave the bow. You need a rest that gets out of the way extra fast, too.”

“Many people ask about lost arrows. Luckily, on the airfield, the grass isn’t used for anything else. You don’t know if it lost a fletch, broke up in mid-air – which can happen. Things are stressed right on the limit. You’ll see people with very long strings, and very short bracing heights. It will give a little more cast, but it makes for a pretty violent shot.”

Optimising arrows for distance is where a background in engineering – and perhaps ballistics – comes in handy. Needless to say, obsessional detail rules the day. Tony Bakes is here shooting longbow: “On most shoots, I will turn up with a dozen arrows, every single one of them different because it depends on which way the wind’s blowing. With a head wind like this you’ll find a heavier shaft will fly further than a lighter shaft. Spin the wind round 180 degrees and a lighter shaft will travel with the wind far better than the reverse.”

“Commercially made shafts such as longbow shafts, are made as matched dozens. But on my longbow shafts I shoot anything from a twelve gram point, about 160 grains, up to about fifteen grams, so 25% heavier and again that depends upon the wind conditions on the day. I try and go for a similar spine because it’s the spine out of a bow that dictates whether it’s going to hit the bow or not, of course.”

“The other thing that a lot of archers will do is move the point of balance of the arrow. A target shaft will have a point of balance that may be strongly front of centre. A flight shaft will have a point of balance that is just a little front of centre, the theory being that it would tend to pivot round that further than if it was further forward. So your arrow would glide before dipping down at the very end, to get more distance. Normally, the more forward the point of balance is, the more stable your shot is. But I’ve also seen arrows here where the point of balance has been a bit too far back, and your arrows can start zipping off every which way.”

Mike Willrich is one of the most experienced hands here, and has, together with his wife, held multiple world records across several different bow styles going back to 1989. I ask him what angle people are aiming for. “On average it’s 45 degrees. Shooting into wind I’ll go for about 43 degrees, but with a good following wind it’s about 47 degrees. I can do it automatically, I’ve been doing it that long!”

Many archers employ a friend and coach and/or a set square to let them know when they’ve hit the right angle. “Essentially, you’re always trying to get the minimum cross section toward the wind as possible.”

Mike’s arrows are home-engineered. “I make the metal nocks myself. You’re allowed to make the nocks, but the points have got to be manufactured.” For recurve vanes, Mike favours an obscure, very stiff material called Flonite, no longer manufactured, although flight archers in unlimited classes have been known to use anything from floppy disks to razor blades as fletchings.

Today, with a headwind, it is not a day for records, although many world marks have been set in the UK. The ‘Superbowl of flight’ is the yearly shoot on the Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah, USA, and Mike has been there many times and set records. “The difference in weather, and in elevation, is huge. In September in Utah it can be between 80 and 100 degrees and very dry. I find I can shoot 10% further out there than here and that’s the humidity. They’re also set up with a following wind – the salt flats are so massive so they can just go anywhere. We’re not much above sea level. You’re 5000 feet up there. The air is thinner and easier to shoot through. And yet a lot of the records are held here in Britain.”

Most flight shoots apart from the main international shoot in Utah are limited in some way or another, due to safety concerns, and the main national UK shoot has moved around before settling here in the 1990s, although they had to briefly move out when the RAF moved on. Practicing is a different matter entirely. Some manage to practice on deserted stretches of beach. Others practice with gaffed ‘flu-flu’ arrows designed to drag and fall to the ground.

Even with the airfield cleared, it can be a lively sport. “When the air force had it, we’d be shooting here and having planes take off and use the side runway. One shoot, we’d just finished and I heard this whooshing noise, and coming over the trees was a hot air balloon, and he’d landed absolutely in the middle of the range. An hour earlier, we’d have shot him.” said Bakes.

Flight archery, while it operates under codified World Archery and national rules, is essentially a self-governing affair. The ‘world championships’, is organised by the USA’s flight archery committee, at the Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah. This is an enormous, flat, dry-as-a-bone stretch of desert in the Southwestern USA best known for being the location for many of the world’s record-breaking land speed record events.

The space is so vast and deserted that the line can be set according to the weather, so a tailwind can be used to advantage. The championships are usually preceded by a smaller event, this year held in the even remoter location of a dry lake bed in Smith Creek, also in Utah, and most travelling flight archers pitch up for both competitions.

In August 2020, because of the pandemic situation, it was a smaller and slightly more subdued affair, without a large international delegation and just a few dozen participants, with the USA remaining closed off to most visitors. In the end, the shoot saw new records in multiple classes including modern American longbow, primitive self bows, and unlimited footbow in the junior class. In a world where the skill of the bowyer can make all the difference, the maker of each bow is recorded along with the records; a remarkable synergy of the archer and their tools.

It also saw a further attempt on the absolute flight record. The all-time record with a conventional hand bow was set by Don Brown of the USA at Smith Creek in 1987, at 1,222 metres. But the absolute flight archery record was set with a footbow by bowyer and archer Harry Drake, perhaps the most legendary name in the sport. In 1971, on a dry desert lake bed in California, he shot an arrow over a mile: 1854 metres and 40cm, a record that has stood ever since.

Many flight archers have tried to best it, and it has obsessed archer and tournament organiser Alan Case for many years. This year, in Bonneville, he came tantalisingly close to the record with a distance of 1816 metres, using a foot bow of his own construction. (In these images it is being shot by junior archer Braylen Pawluk.)

Alan takes up the story. “This obsession to try to take this record has evolved in small increments since 2005. I figured at the time it shouldn’t take much longer than a year to break that record!” he laughed.

“Each year I would run into a limit that would challenge my progress. The first was understanding how to optimise the design so that the bow was able to efficiently deliver almost all of the energy in drawing the bow to a very light arrow.”

“Next it was figuring out the most efficient way to support and release the arrow so that it could be drawn much further than the arrow was long. I decided to take a completely different route than the crossbow-like approach Harry Drake used. This allowed me more flexibility to shoot a wide variety of arrow lengths and diameters, but it had the drawback of requiring more attention to set up each shot, or it would result in disaster.”

“As the bow performance increased from year to year, the next step was focused on safety. This included the addition of shields to deflect an exploding or misaligned arrow. Once I was able to reach about 1200-1300 yards, I hit a barrier that took several years to break. No matter how fast the bow shot, the arrows just wouldn’t fly any further. This required me to focus on the design of the arrow. I learned all I could about the aerodynamics and projectile dynamics of rockets, to javelins, to aircraft. “

“I kept a detailed log of the performance of each arrow, and learned what characteristics to keep track of. For example, the entry angle of the arrow into the ground is an important indicator of whether the arrow design is the limit of how far it can travel. This drove changes in how I designed the arrows and suddenly distances started improving again.”

Case added a tuning device which could be mounted onto the front of the bow, giving a ‘paper tune’ similar to that uses by target compounds, and the goal is the same: to get a perfect bullet hole. “As distances increased, the next barrier was being able to find the arrows. This required focus on accuracy. It is much easier to find an arrow that lands within a meter or two of the shooting direction, so I worked on techniques to aim and deliver that arrow as close to the line as possible.”

“The next issue was durability. A bow that lasts only a few shots is impossible to tune, and not much fun. So I had to focus on optimising the mix of materials in the limb and working out the best way to bond the materials together to get a bow that is both durable, and extremely efficient. This takes me to the present. What else have I learned? I learned to have a sense of humour about this pursuit. I enjoy the friends that I have made along the way, and have enjoyed constantly learning something new.”

While the ultimate record remains intact, you sense that as long as it remains, Alan and others will keep searching forever for ways to beat it. Flight remains a tiny concern, but you feel it will remain as one of the most vital, challenging sides of archery. While the USA and the UK have the most active flight archers, there is activity around the world, in countries including Italy, Norway, Hungary, Australia, and Taiwan.

It’s not just you against yourself, it’s also you against your own skills, your materials, the environment, and many other things. As a archery challenge; it demands something deeper.

USA pics courtesy of James Sanchez and Alan Case, with great thanks.

I enjoyed reading the article. I shoot the longbow and have entered a number of Clout competitions and I am interested in entering this years flight competition.

I make all my equipment and have some barrelled footed thin shafts but I have been unable to find fletchings as small as those suggested.

Is there anywhere you would recommend looking – or is it a case of buying parabolics that i can cut down.

I would welcome your thoughts on whether I should enter and on where I should look for equipment.

Best Regards

Dave Harrison