Jan H. Sachers walks us through early biography of the scholar and author of Toxophilus

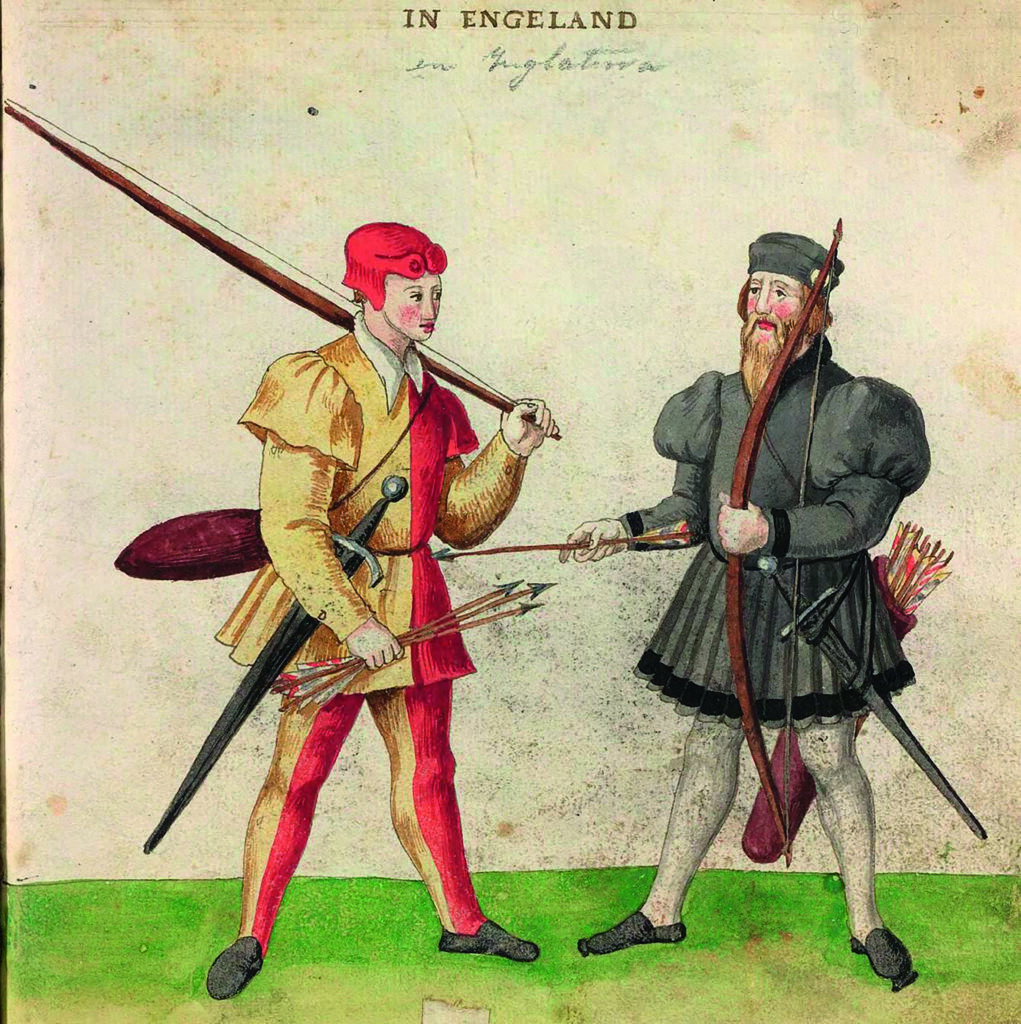

‘Toxophilus, the Schole of Shootinge’ is the oldest known archery manual in Europe – but Roger Ascham’s opus magnus is actually much more than that. It was first published in 1545, the year the Mary Rose sank near Portsmouth. It was a time of political, religious, and cultural turmoil. Firearms were replacing the time-honoured longbow in the armouries and on the battlefields. In society, a new class of educated citizens were challenging the positions of the nobility in government and administration. And new humanistic ideas were spreading across Europe, changing the conventions of cultivation, and the doctrine of what constituted ‘the complete man’. Reasons enough to take a closer look at the author and his work.

EARLY DAYS

Kirby Wiske is a tiny village and civil parish in the Hambleton District in the North Riding of Yorkshire. Here Roger was born around 1515, the third of four sons of John Ascham, a steward to Henry, 7th Baron Scrope of Bolton. His mother Margaret may or may not have been related to the Conyers dynasty, but this detail is as uncertain, as are many others relating to Roger’s origins, childhood, and youth.

He received his early education in the household of Sir Humphrey Wingfield, a wealthy lawyer and distant relative, in Suffolk. This is where the young Roger discovered his love of and talent for languages, as well as the other great passion of his life: archery. As he later recalled in his letters, it was his host who personally brought bows and arrows back from London, supervised the shooting of the pupils living in his house, and handed out the best equipment as prizes: “[…] and he that shot fayrest, shulde haue the best bowe and shaftes, and he that shot ill fauoured lye, shulde be mocked of his felowes, til he shot better” (Tox p. 140). Even in his later years Ascham still praised his benefactor for introducing him to ’the book and the bow’.

[Public Domain]

THE SCHOLAR

Sometime around 1530, probably at the age of 15, Roger Ascham enrolled at St. John’s College in Cambridge, his academic home for many years to come. As one of the great centres of learning, the university was profoundly influenced by the new ideas. One indicator of the changing intellectual atmosphere was the revival of Greek as an academic subject, to the study of which Ascham immediately devoted himself. He began tutoring his fellow students, because he considered the process of teaching the most effective way to learn a language.

On 18 February 1534 Ascham received his B.A. and was made a fellow of the college. Continuing to study and teach he took his M.A. degree on 3 July 1537. His main subjects besides Greek were rhetoric and dialectics, but he even held lectures in mathematics. He was well liked and respected, though his pro-reformation stance did not universally meet with approval. And according to later accounts by contemporaries, as well as his own letters and memoirs, Ascham spent as much time as he could practicing archery – a pursuit that earned him a certain amount of criticism, even ridicule.

Strictly speaking he was simply adhering to the mandate issued by King Edward III in 1363, and often renewed, lately by the present king Henry VIII, obligating every able-bodied man to own bow and arrows, and practice their shooting on Sundays and holidays. However, clerics and university members were officially exempt from this rule, and the scholars of the time regarded physical activity beyond a philosophical stroll across the college grounds as unbecoming and undignified.

Engaging in sports of any kind also implied the possibility of betting, which to papists and reformers alike, was almost as bad as the despised vice of gambling. And although King Henry VIII himself was a dedicated and capable archer, his habit of holding tournaments with his courtiers and shooting for considerable sums of money didn’t help much to redeem archery in the eyes of the self-proclaimed guardians of virtue.

Hence Ascham later went to great lengths in Toxophilus to defend his passion against such suspicions. On the contrary, he believed archery to be a virtuous and laudable pastime, actually discouraging its practitioners from such vices as cards, dice, or other games of chance, and less prone than ball games to physical altercations. Moreover, it was practised in the open air, in the light of day, surrounded by God’s natural gifts – not at night in dark, ill-reputed taverns.

However, Roger’s enemies used his passion for archery against him, claiming it kept him from serious academic research, pointing to the fact that despite all the years at university he still had no publications or concrete contributions to knowledge to show for them. These enemies were mainly competitors for prestigious, well-paid college positions; Ascham had realised he would never be able to sustain a family with his rather meagre fellow’s income. He had also begun to look for rich, influential patrons at court, in church or the administration, but with little success. His letters from the early 1540s reveal a man torn between his love of the quiet, comfortable life in Cambridge, where he could follow his studies and his passion in peace, and the urgent desire to improve his position and financial situation, and to fully utilise his talents and education.

LOVER OF THE BOW

1544 was a painful year for Ascham, then 29. He heard that his parents died on the same day after 47 years of happy marriage. This event came soon after his older brother Thomas had also died. In the last letter John Ascham had written to his son at Christmas 1543 he had urged him to leave Cambridge and find “some worthy manner of living”.

Roger’s colleague and friend of many years, John Cheke, left the university in 1544, which meant not only the loss of an intellectual brother-in-arms, but also of an influential supporter. A little while later his favourite student and protégé William Grindal was passed over in the selection of a new reader of Greek, which, according to his letters, Ascham considered a personal affront. Determined to support the young man despite the setback, with the help of John Cheke he was able to secure Grindal a position as tutor for the eleven-year-old princess Elizabeth.

With the death of the Archbishop of Cambridge on 13 September 1544, Ascham lost an annual stipend of 40 Shillings, which had helped support him for the past three years. He was left still holding the same position as Reader of Greek with an income of as little as £3 per year, and surrounded by fewer friends and supporters, but a growing number of foes and competitors. With no publications or other proofs of his intellectual capacities and achievements, Ascham’s future did not look bright. True, he had established links with a number of powerful and influential figures, but he had to compete with a host of others for their patronage and finite resources.

We know from his letters that Ascham had been working on a book ‘in re Sagittaria’ (‘concerning archery’) since at least 1543. He meant to present it to Henry VIII in person before the King’s departure for France, but the plan failed, because the book was still at the printers when the fleet left on 14 July 1544. He recalled the manuscript for a final revision, intending to present it to the King upon his return instead.

His hopes were again dashed when Henry’s army scored a series of victories in surprisingly quick succession and returned to England early, in September 1544. For his part, Ascham seems to have substantially revised and extended the original manuscript; in February 1545 he confessed in a letter to his friend Grindal that he had even stopped reading his favourite author Herodotus in order to focus solely on his book.

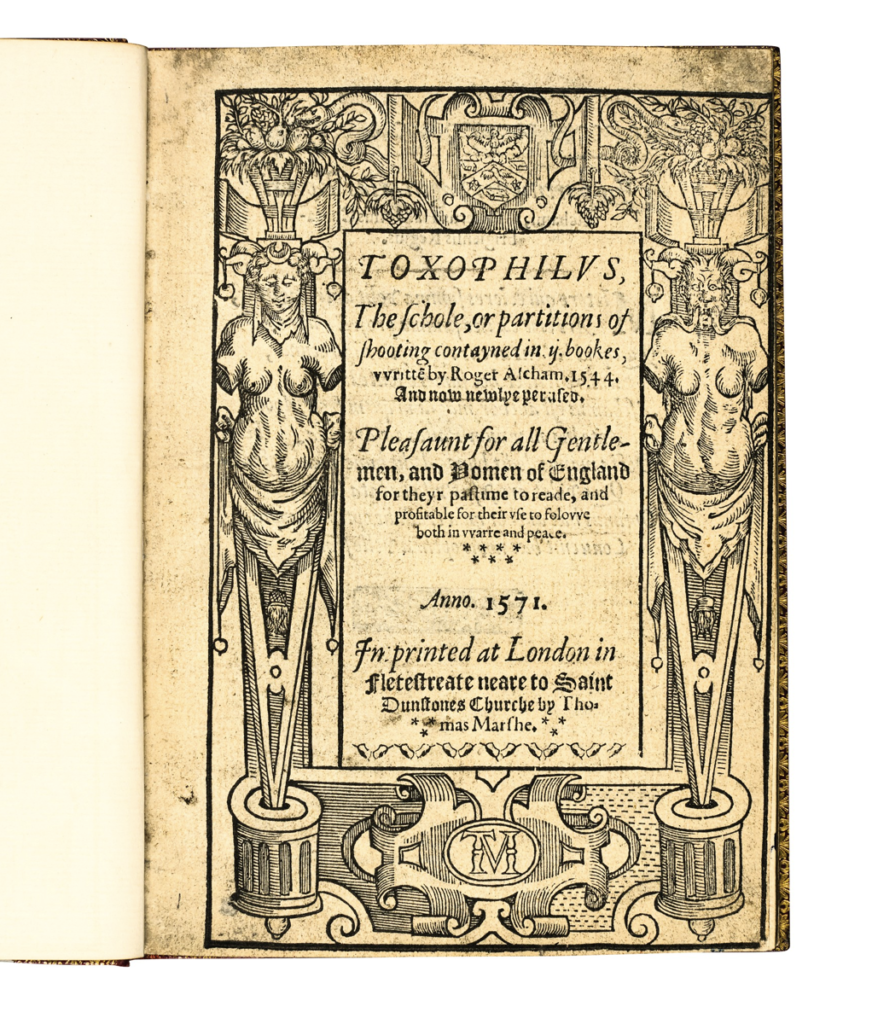

‘Toxophilus, the Schole of Shootinge’ was finally published in that year. It was dedicated to Henry VIII, but since he was not able to hand over a copy in person, Ascham sent one to the privy council instead. In the event it was well received, and earned its author an audience with the King in Greenwich. Unfortunately, no records exist of the exchange between those two passionate archers, but one result of their meeting was an annual Royal stipend of £10, which more than doubled Roger’s income and helped his financial situation enormously.

High ranking dignitaries like Bishop Gardiner and the Duke of Norfolk had supported him, and overnight Ascham’s name became known in the highest circles. Now that he enjoyed the patronage of the King, it would be difficult for his enemies to use his passion for archery against him, or indeed to discredit the sport itself. Though he still lacked a secure position both professionally and socially, he was helped by his nomination as Public Orator at the University in succession to his old friend and mentor John Cheke – which also came with a very welcome forty shillings a year.

TEACHER, SECRETARY, DIPLOMAT

In letters written during this phase of his life, Roger Ascham expressed growing discontent with his situation in Cambridge. So, when William Grindal died in 1548 he successfully applied to succeed him as tutor of Greek and Latin for the then 14-year-old princess Elizabeth. However, after some unspecified legal dispute with the royal court he returned to Cambridge only two years later – albeit not for long – where he was offered, most likely courtesy of influential friends, the position of personal secretary to Sir Richard Morrison, the newly-appointed ambassador to the court of Emperor Charles V. Ascham spent the next few years travelling the continent. Some of his reports were later published under the title ‘Report and Discourse of the State of Germany’.

His diplomatic mission ended with the coronation of Mary I, but the Catholic Queen appointed the reformatory scholar as her secretary for Latin correspondence instead. After her sudden death in 1558, Ascham fulfilled the same role for her successor, the protestant Queen Elizabeth I.

He married Margaret Harleston (born circa 1528) on 1 June 1554, and they had at least four sons and three daughters together. But, as a married man, Ascham had to give up his positions at the university, and since Margaret was not particularly wealthy either, he once more called upon his benefactors at court. He managed to buy a rather stately manor house called Salisbury Hall in Walthamstow, and he and his family led a fairly comfortable life, despite his persistent precarious finances.

In 1563 Ascham began his second major work ‘The Scholemaster’, a kind of manual for private tutors which not only contained a complete syllabus for Latin, but also the author’s surprisingly modern views on how to teach by encouragement and assistance, rather than discipline and punishment. Ascham fell ill just before Christmas 1568 and died at the end of December, probably from malaria. The book was first published in 1570. As an elegy published in 1576 noted: ‘[H]e liued and dyed a poore man, leauing behind him two most excellent bookes, as monuments of his wit, in the English tongue, wherof he intituled the one Toxophilus, and the other Scholarcha.’

Caption: Toxophilus 1 and 2 [Ascham, Toxophilus, London, 1571, private collection]

Several editions of ‘Toxophilus’ were published from the 16th to 18th centuries, and later editions appeared in 1868 and 1902. The book enjoyed great and lasting popularity amongst the nobility and gentry alike, and it was often cited by authors like John Smith, William Neade, and Gervase Markham in their arguments against the abolition of the bow as a weapon of war.

Quotes from Ascham’s opus, sometimes almost verbatim, can also be found in the works of poets like Shakespeare, Samuel Daniel, Ben Jonson, Robert Burton, and John Milton. Reading it today not only provides entertainment, but also interesting and valuable insights. Who would have expected such a great and long-lasting success? Least of all its author, this poor bow-shooting scholar from a tiny village in North Yorkshire!

The contents and structure of ’Toxophilus’, and thus the reasons for its continued popularity, will be the subject of the second part of this article.

REFERENCES

Roger Ascham: Toxophilus, The Schole of Shootinge, London 1545.

Lawrence V. Ryan: Roger Ascham, Stanford 1963.

Harald Schröter: Roger Ascham. Toxophilus, The Schole of Shooting, St. Augustin 1983.