Taking archery to the grave. By John Stanley

The British Museum in London is currently holding an exhibition called The World Of Stonehenge, which is open until the middle of July 2022. There’s less in there about the titular monument itself and more about the age and its people. It broadly follows the story of Britain (and Europe) from around 4,000 BC to 1,000 BC, an age of transformation, ritual and beliefs, the last of which we are still only beginning to uncover.

There are many objects to catch the eye; polished stone axes that apparently travelled all the way from Italy, astonishing worked gold jewellery and something called the Nebra Sky Disc, which was the world’s first map of the stars and certainly one of the most beautiful yet made. The objects that belonged to another well-known character in the Stonehenge story are a lot less showy, but they tell just as interesting a story.

In May 2002, a team of archaeologists were digging up Roman remains on a housing development site at Amesbury, about three miles from Stonehenge, when they discovered a Bronze Age grave of a man who would come to be known as the Amesbury Archer.

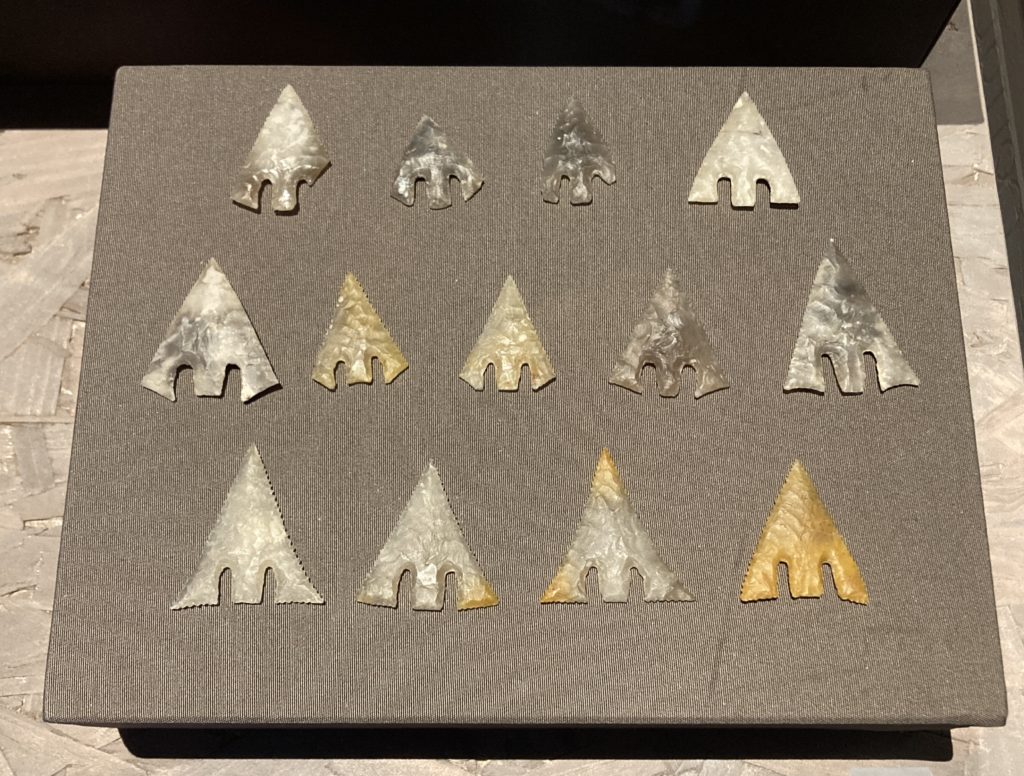

Buried about 2400 BC, the contents are some of the finest ever found from the era and included 15 finely worked arrowheads of a design known as ‘barbed and tanged’, as well as two stone wristguards, one of which appeared to have been on his arm when he was buried.

As well as the objects that marked him as an archer, there were gold ornaments, metal knives made from French and Spanish copper, a metalworking stone, and much more. Isotope analysis of the archer’s teeth proved he came from the area of Switzerland, or perhaps nearby Germany or Austria.

Whoever he was, he was an important and influential person. The burial, so close to Stonehenge and at an age we know involved some of the key building phases of the monument, led some media outlets to upgrade a mere archer to the ‘King Of Stonehenge’. The who, why and how of the building of Stonehenge has been occupying archaeologists for centuries, but we know for such a vast effort, somebody must have been in charge. Was it him?

He’s not the only archer in the neighbourhood. A similar Bronze Age shared family grave nearby also contained flint arrowheads, which led to the occupants being dubbed the Boscombe Bowmen.

In 1978, a Bronze Age man’s body was discovered in the outer ditch of Stonehenge itself. He was also buried with a stone wristguard and arrowheads, although alarmingly, several of the arrowheads were embedded in his bones. It appears he had been shot to death and then carefully buried in the ditch. This man is known as the Stonehenge Archer.

Elsewhere in Britain at the same time, people were buried not only with flint arrowheads, sometimes exquisitely worked far beyond functional necessity, but also with flint ‘blanks’ for making arrowheads, which appear to show beliefs about the needs of the dead in the afterlife.

The stone wristguards are perhaps most interesting of all, as they are found in graves across Europe and often do not appear to have been either used or designed with function as a regular bracer in mind. Some are made from fancy imported stone or have unnecessary gold rivets added on. Wristguards made from stone are relatively impractical anyway; examples from indigenous cultures around the world more commonly use animal hide, horn or some other organic material.

If the occupants were really archers, this was their ‘Sunday best’ equipment. The wristguard had clearly moved beyond function, a tool of the trade, to become a status symbol, perhaps indicating prowess in hunting or war.

It also illustrated the status of archery in a time when such skills appeared to be important not only on a practical level, but on a spiritual and ideological one as well. We all know some of the epic tales from history that intertwine the bow with human values such as bravery and strength, tales that occur across millennia. Archery is repeatedly presented as a powerful and prestigious skill in life and a celebrated aspect of identity.

For the Amesbury Archer, a high-status man living in an era where farming had replaced hunting as the basic way of life, his burial would see him sent off as a warrior, the bow venerated as a symbol of individual and perhaps even political power. It is clear that archery equipment held a magical, cosmological charge, the remnants of which are still with us today.

The World of Stonehenge continues at the British Museum until 17 July 2022.