Hugh Soar takes a look back at the history of bow sights

When today’s competitive archers glance at the gold through the lens of their chosen bow sight, they may be forgiven for not reflecting upon the antecedence of these now most elaborate and essential objects. But the sight’s purpose has rested upon ingenuity, advance and adaptation across the centuries, for ‘sighting’ has become the prerequisite of accuracy.

Two simple aiming aids preceded the present set-ups, one an attachment to the bow, the other secured to the bow-hand, and we’ll glance at each.

In the mid-1870s James Spedding, a competitive archer and member of the Royal Toxophilite Society, seeking to improve his scores took a dressmaker’s bright bead pin and attached it to his longbow’s upper limb. This he arranged to adjust horizontally or vertically at will to line up with the gold at each distance. With the proviso that he held it steadily on the target as he loosed, he found his scores improved.

While his use of this device was noticed by his companions, they dismissed it as a passing novelty. As he subsequently remarked, he wished that one or more had complained about its use as ‘unfair’, when he would have known that there was ‘something in it’. But its presence went unremarked and this vestigial ‘pin sight’ concept died with him. Spedding died in 1880, knocked down and fatally injured by a speeding horse-drawn carriage.

Trajectory

At about the same time, at Meriden in Warwickshire, Lord Aylesford – founding member of the Woodmen of Arden archery society – had hit upon a novel system for potential accuracy. When shooting clout, his lordship was seen to tie a piece of string to his bow hand, from the end of which dangled a knot. When his bow hand was raised, this knot was aligned to the ‘clout target’ and the shaft released. With a consistent trajectory thus established, his accuracy improved.

This concept was also seemingly disregarded as idiosyncratic whimsy by his fellow Woodmen, however, and as with the pin sight it was not generally adopted. I have shot regularly at Meriden and the ‘Meriden wind’ has been a notable feature. Lord Aylesford’s device would have been ineffective in anything more than still air.

Archers are not noted for their acceptance of new ideas and it was half a century before the bow sight as an aid to accuracy reappeared. Looking at earlier means of establishing accuracy, we turn to Roger Ascham’s 16th century book Toxophilus.

Ascham deplores the practice then of paying more attention to the shaft than to the mark or target. He commends those who shoot ‘streighte’ for they have “invented some wayes to espy a tree or a hill beyond the marke, or else to have some notable thing betwixt the markes” at which to aim.

He adds: “ones (once) I saw a good archer which did cast off his gere and layed his quiver with it, even in the mid-ways between the prickes. Some thought he did it for save-guard of his gere; I suppose he did it to shoote streighte withall” – an early use of the modern ground-based aiming mark.

Fast forward now to modern times and the vagaries of international competition; these had begun in a modest way through five competitions held intermittently between 1904 and 1913 at Le Touquet in France between English and French, Belgian and Swiss archers. Although aiming aids per se were not a feature then, evidence from contemporary bows suggests that marks on limbs may have been used.

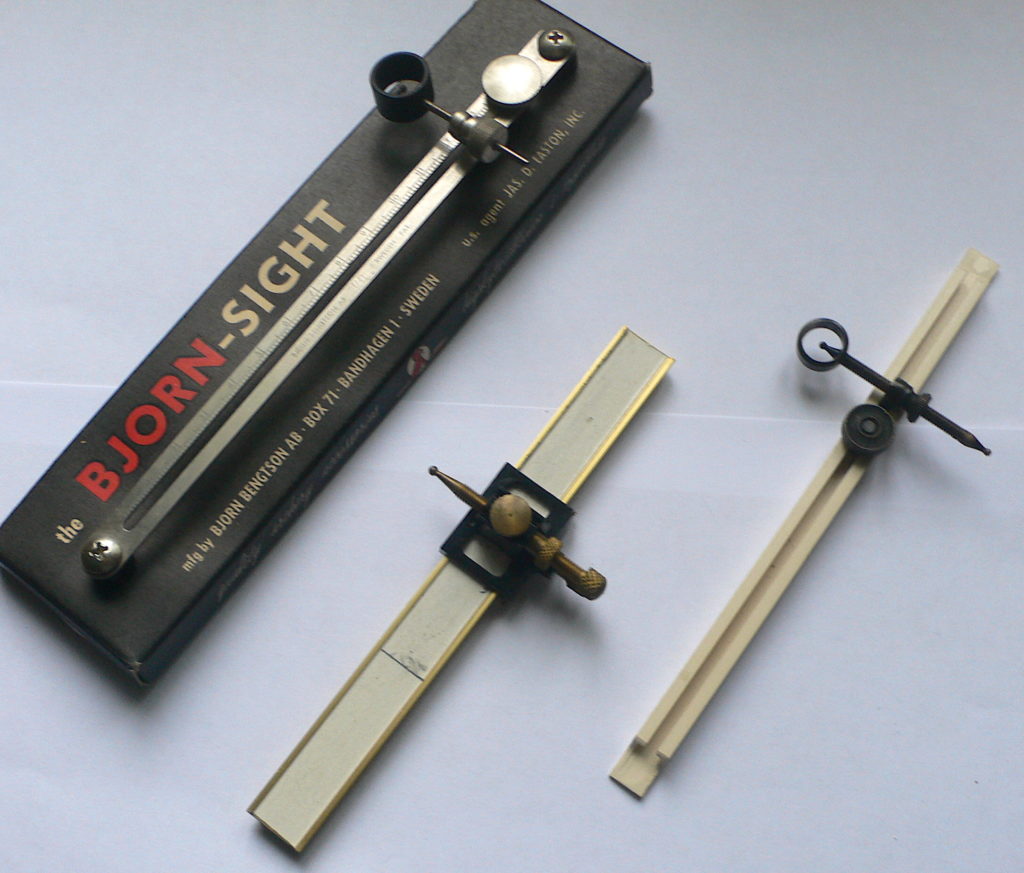

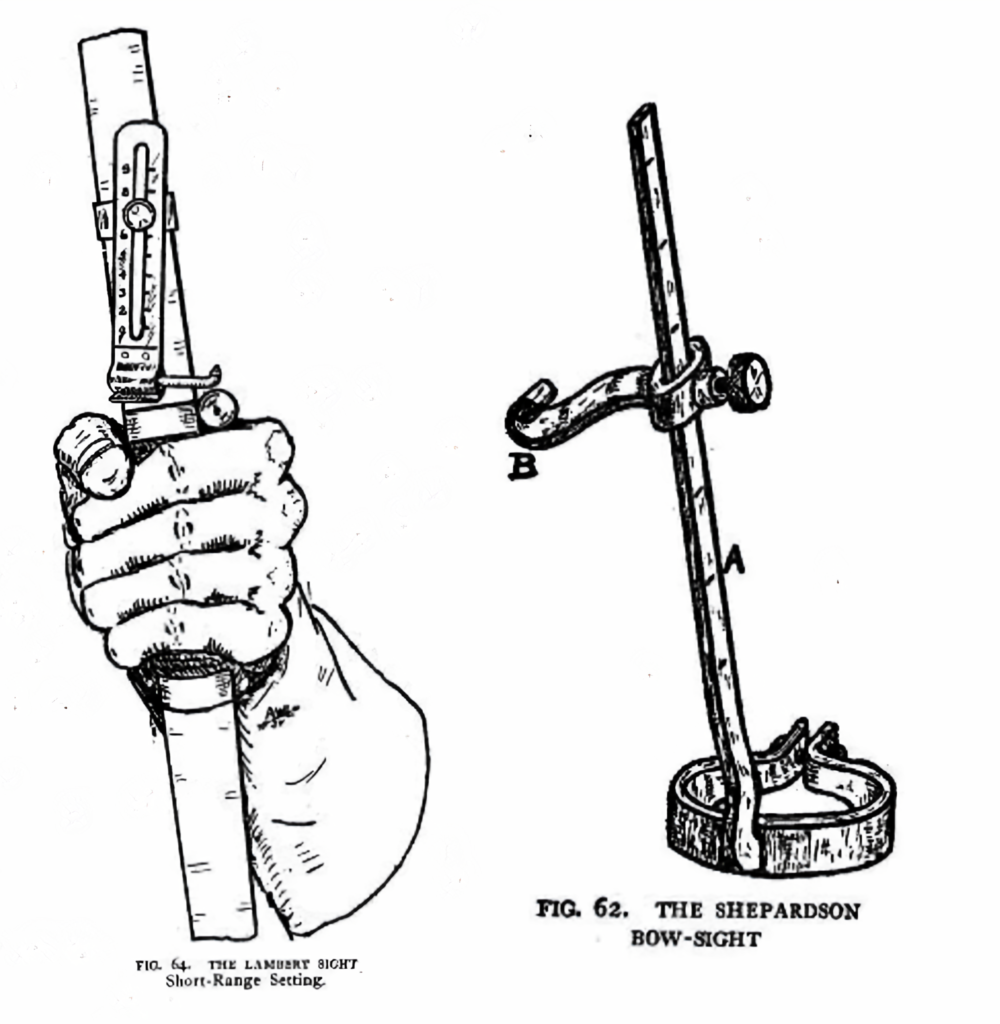

Two of the earliest commercial bow sights from the 1920s: the Shepardson and Lambert sights (see above) were clamped on the longbows of the time and provided a forward sight for aiming much as we do today. It was not until 1932 when, with the formation of FITA and the revival of international archery meetings, acceptable aids to accuracy were debated and had a rough ride to start with.

In that year; the Technical Commission put its foot down, a motion was carried that “special sighting devices and any accessories or attachments on bow or string were prohibited”. England and Sweden abstained.

In 1933, the US went further, proposing a motion categorically prohibiting the use of “all accessories, visual sights, reference marks of any kind, on arrow, bow, string, hand or ground”. This proved a step too far, however, for following a ‘heated discussion’, it was agreed that the secretary general of FITA seek the view of each nation on the subject, reporting back the following year.

The year 1937 brought a great deal of discussion about ‘nocking positions on strings’, it being finally agreed that one point only should be allowed. Article 23 of the Rules informed in the matter of the bow-related aid, now seemingly an accepted feature. “Dioptric sights are not allowed, only a mark on the bow, arrow or hand is allowed. The mark should be easily effaced and/or changed as needed. An attachment on the string is now also permitted. Bow limb bandages are allowed but require a seal authorised by the Technical Commission.”

Linguistics

In 1946 there was an interesting discussion on linguistics. The FITA Rule allowing a ‘line’ on a bow limb prompted a comment from Denmark, which pointed out that in Danish ‘line’ meant either a marked line, or a string or cord. Matters were settled by a more exact definition – a removable mark – and things settled down once more.

There was more concern about strings in 1949. It was to be permitted that “an attachment to the string not exceeding 1cm is allowed in addition to the nocking point” – today we call this the ‘kisser’ – while 1950 brought a new matter into perspective, the introduction of “points of aim on the ground”. Despite opposition from South Africa, these were to be permitted as an experiment. However, they were not to stand more than 6in above ground, nor exceed 2in in diameter.

In 1952 the pin sight proved a sticking point; an American motion to introduce these was turned down by six votes to five. In 1953, Britain had second thoughts about introducing a motion forbidding ground ‘points of aim’ and withdrew it. In 1956 there were second thoughts about pin sights, which were accepted by 14 votes to four. The Technical Commission felt they should be standardised so in 1957 affiliated nations were invited to consider features and report back.

Standardised pin-sight dimensions were finally authorised in 1958, but by then technology had advanced and ‘microhole’ glasses had become a nine-day wonder on national shooting lines. Predictably these were promptly banned, although spectacles per se were understandably permitted.

By now the Technical Commission was probably becoming fed up with abortive attempts by members to circumvent the principle of simplicity inherent in FITA’s founding aim. They therefore found it necessary to restate what was permitted and what was not. Thus, while ‘simple’ pin sights were allowed, as were bow marks, ground points of aim and additions to bow-strings, sights involving a lens or prism were not.

It was not until 1974 that things progressed, when “bow sights attached to bows may allow for windage adjustment as well as elevation setting for aiming but shall not incorporate a prism, lens or other magnifying device”.

Conventional spectacles, gloves/tabs, arm guards and bracers, and quivers side and ground were understandably allowed at all times.

Hard fought

It will perhaps surprise international competitive archers of today, accustomed to complex – and increasingly expensive – bow sights, that until the early 1970s their 20th-century predecessors made do with a simple bow-mounted pin, or pin and ring sight, hard-fought for acceptance against a reactionary FITA Technical Commission, and still an optional ‘add-on’ when ground-based ‘points of aim’ were largely in use.

It was a founding principle of FITA that competitors from member countries should use a ‘local’ bow. The concept of

a ‘standard’ bow was not yet in keeping with the philosophy of inter-country competition and ‘local’ bows were expected and encouraged.

This worthy principle foundered somewhat when Sweden produced the steel bow. It had become apparent, however, that not all ‘local’ bow styles produced equal results, and the Technical Commission was obliged to define a ‘standard bow’, the rules for which are still in place.

Back to the sight, and the modern take on the perpetual problem of shooting aids. Current proscription continues the ban on prisms or any other magnifying device for recurve bows. Advances in construction are recognised, however. A ‘bow-sight extension’ with ‘windage’ and ‘elevation adjustment’ is now permitted, and a scale, or tape with markings incorporated as a distance guide is allowed while ‘not offering any additional aid’.

(A minor but perhaps significant modern inclusion is constant reference to the present-day male shooter as an ‘athlete’. It is a well-earned and logical description now, but one that would have pleasantly surprised some of the pipe-smoking, beer-bellied 1950s predecessors.)

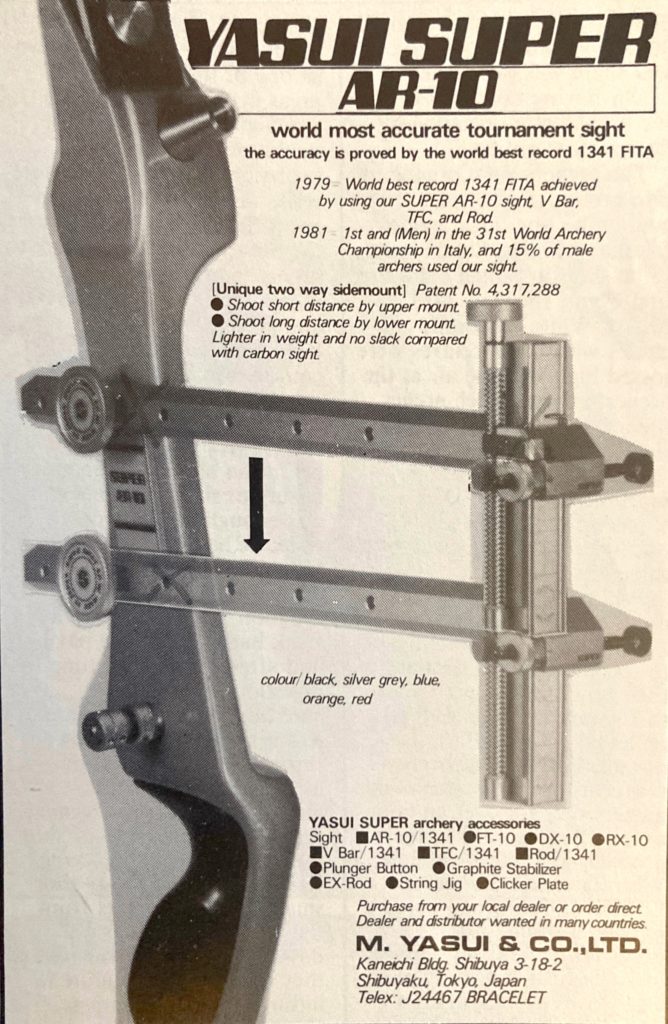

In modern recurve competition, for many decades top competitors used simple rack-and-pinion sights with perhaps only two adjustable axes. An ‘arms race’ between the top US and Japanese manufacturers has resulted in modern sights with complex multi-axis micro-adjustability via countable clicks and esoteric designs to eliminate ‘backlash’ amongst much else. Target archers are, of course, more accurate than ever before – although the sight cannot take much, if any, of that credit.