Club archery has a problem. By Chris Wells

Shooting a bow effectively requires the knowledge of the movements required and the muscle memory and physical fitness to deliver those movements identically each time.

It’s easy to learn bad habits and it’s easy to lose comfort in shooting. These can both be exceptionally demoralising, especially if archery is a hobby and not something that a person would like to take to a high competitive level, let alone international level. But, as with many things in life, people prefer to run before they can walk. That can manifest itself in archery as buying expensive equipment before it becomes necessary, increasing draw weight on a bow without the physical attributes or training volume to make it worthwhile, or expecting scores far higher than are reasonable.

Both of these lead to countless numbers of people walking away from the sport each year because it becomes unmanageable or, simply, no longer fun. And that’s not okay. Clubs should do more to ensure that members are protected from simple pitfalls that can be a massive turnoff.

…and no idea

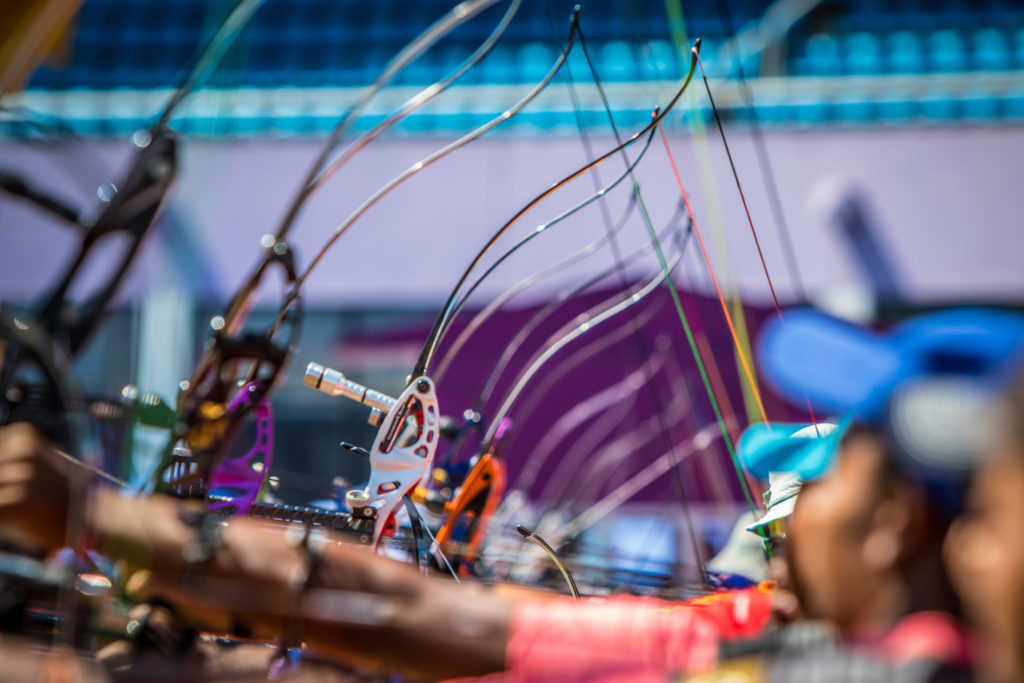

In a game of millimetres, having precision manufactured equipment of the highest standard makes a difference – but not if the margins of success of the athletes behind it are still measured in centimetres.

There’s a simple line of progression of expensive gear that any beginner-moving-to-intermediate in the sport, learning with a recurve bow, should stick to: tab, then riser and grip, sight, stabilisers, then limbs, then arrows.

The reason for this order? An archer’s most important connections with his equipment are the two hands – on the string and in the riser.They’re also the two points that don’t change as the weight or shape of the bow does, unlike arrows that require different spines and tuning.

A good sight will last an archer a long time and while stabilisation will likely need to be adjusted as weight increases, the basic V-Bar set-up is applicable across the board.

Of course, this order is more difficult for compound because the limbs and riser are integrated – and expensive – but the principle of starting with the connection between archer and bow and working outwards still applies.

Draw weight

Even at the international level, there are some archers that cannot fully handle the weight beneath their fingers at full draw. Shaking under a heavy bow is not a good look – and definitely not conducive to consistently hitting high scores. There are exceptions to this rule, such as Italian international Mauro Nespoli, but even he doesn’t encourage people to follow him directly down that path.

The simplest analogy is writing with a pen on paper: write a sentence normally, and then try to write the same sentence with all the muscles in your hand and forearm tensed hard. No matter how bad your handwriting is, the first attempt is going to be smoother.

Each arrow should be like the smooth sentence, whether it’s the first in the end or the recreation according to their goals. Being able to swap limbs in for a slightly higher weight at minimal cost makes this process much more viable. The limbs coming out of the shop are unlikely to be brand new but as long as you take care of them, as everyone should, it’s an excellent system.

But when to swap? The short answer is: slowly. A lot of club archers jump up in weight way too early. Shooting shorter distances on a lower poundage while basic technique is built is highly undervalued, especially in the UK. It’s often a race to get the distance rather than the skill, as progression in the UK archery grading system requires long-distance shooting – and it’s frequently a mistake.

Sticking at low weight for an extra couple of months after completing a beginners course is likely to reap benefits later down the line, especially if that’s followed up with incremental steps of weight increase – four pounds maximum at a time – after that. As long as any increase remains comfortable, it should prevent bad habits like a backwards lean, poor drawing form and even target panic creeping in.

It’s difficult to define comfort with weight because it depends on how much a person shoots in a day and how often they shoot in a week or month. Whatever the regularity is, the last arrow of a shooting session shouldn’t feel like the last arrow that a person can shoot. It’s better to build strength using other techniques than waste arrows by shooting them poorly.

If you are just an occasional shooter, weight will compound problems even faster. It’s not just that they won’t be executed as well as the others but that they will have a negative effect on positive muscle memories.

Expectation v reality

It’s important to have goals at all levels and archery is fantastic for that. Goals can be so tangible – scores are numbers after all – and it’s easier than other sports to measure progress.

But the race for weight to reach a certain distance to produce a score against which to measure an archer against others, which happens at the club level, can be implemented incorrectly. There’s often less of a focus on staged progression than there is on making big jumps, which aren’t sustainable. It’s a normal human reaction though; it suits the ego to say ‘I can handle this’ and it fits in with the ethos of challenging yourself hard. It might be a little less sexy to spend extra time shooting, say, 200/360 points three times on a big face at 20 metres before progressing to try and hit 250 points the same number of times, but it’s no less rewarding – and consistency is what’s important in archery.

The award systems administrated by national governing bodies are a start, but there’s more that can be done at the grass roots level to help people progress step-by-step. And if that happens, we’ll have less people turned off by the simple issues caused by starting out wrong. And more people sticking around at the archery field.