How clubs made rules and kept house in the 18th century. By Kristina Dolgilevica

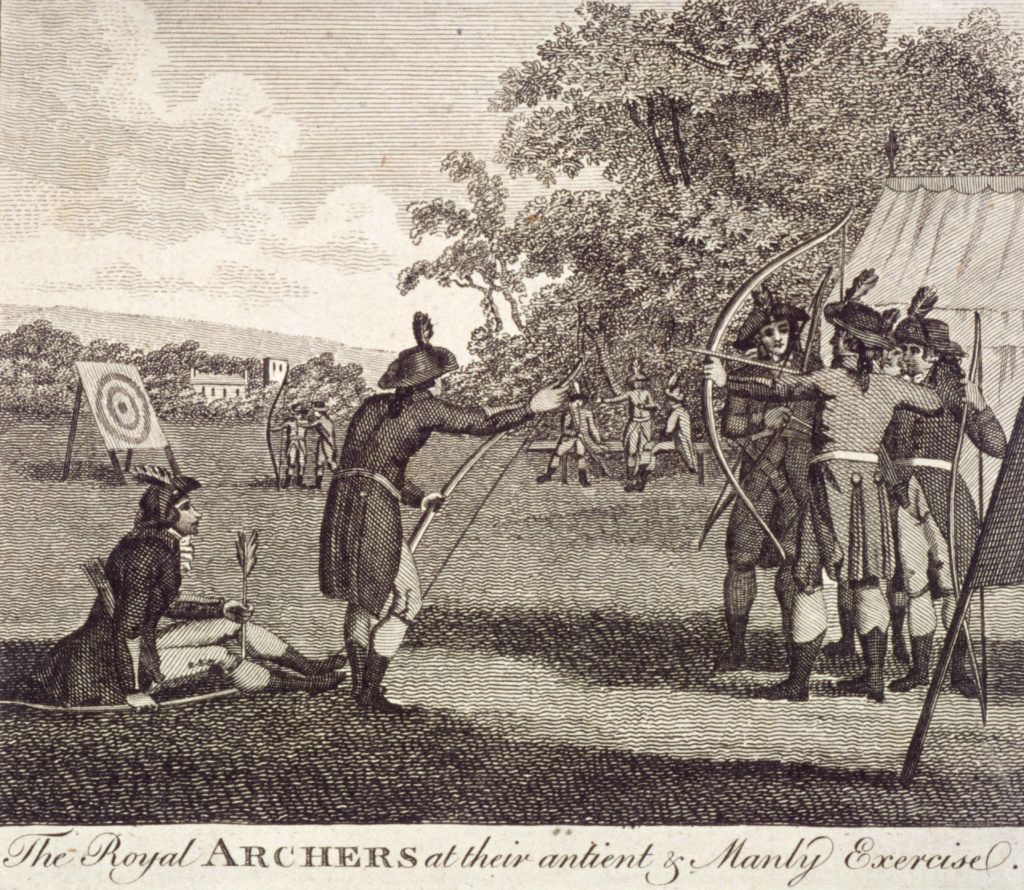

For the past few years the subject of my ongoing historical research project has been the archery societies of the late 18th century England and Wales.

The revival of archery practice at the end of the century formed the middle ground between the old traditions and laid the foundations for the great revival of the Victorian era and beyond.

The interest in this particular area lies in the fact that there has never been a single study attempting to bring all the facts and figures together to form a more coherent picture.

Evidence is fragmented or scattered, and secondary writing on the subject is often inadequate, and at times biased. The most important primary source is the societies’ rule books.

Composition of the Rule Books

The rule book is a document, which originated in the founders’ first meeting, and was a result of a discussion between the original members of that society.

Basic rules were outlined in manuscript in the form of minutes, court-style records. Once the society was more established, attracted more members, the minutes were formalised, and printed by and for the use of the members of that group only.

The general structure of the rule books is largely consistent from one society to another, though they often varied in the order of the topics dealt with. The following were subject to formal regulation: eligibility for membership, appointment of officers, subscriptions and disciplinary matters, places and dates of meetings, shooting rules, and dress code.

The rule books would be appended by a members’ list in print or in manuscript. Institutors, (the people who started the societies), honorary members, and genders were distinguished by specific marks or separate columns.

For example, ’’O.M.’’ would stand for ‘original member’ and ‘ladies’ and ‘gentlemen’ would appear in separate lists. Some books are found with manuscript amendments and additions to the members lists, suggesting a limited readership.

Appointment of Officers

One of the first matters to be addressed, then and now, was the appointment of club officers. Duties of officers were not always described, but the terms for which they served were always stated – typically the role was either annual or perpetual.

Many institutors often held perpetual positions. Every society would appoint a president, a vice-president, a secretary and a treasurer. These posts would typically be filled by members, though sometimes outsiders were employed to deal with a society’s income.

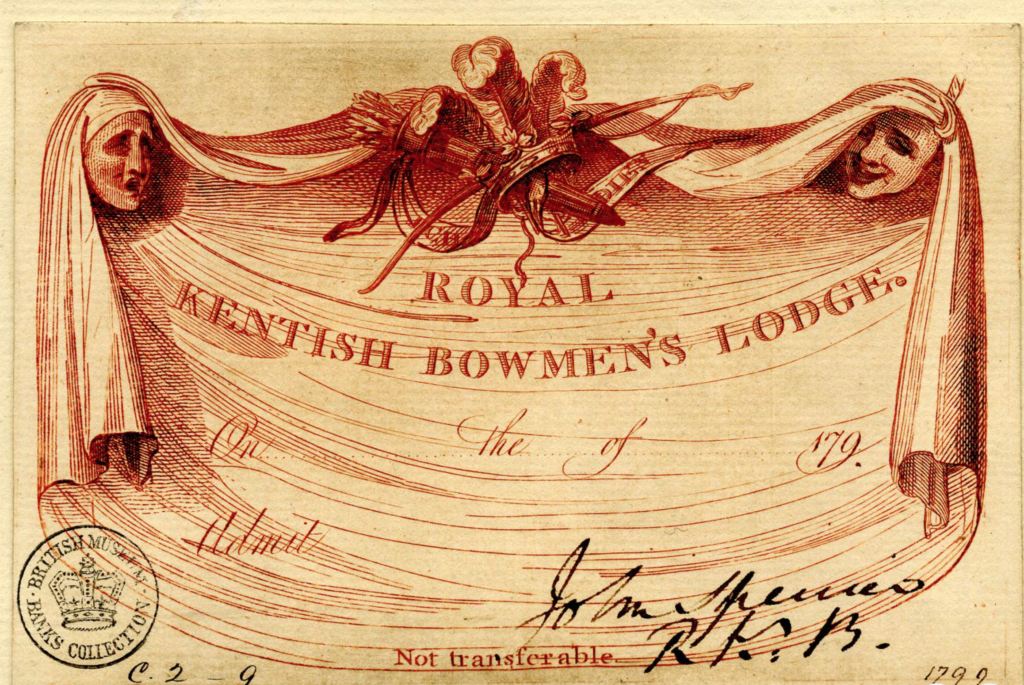

For instance, the Royal Kentish Bowman’s treasurer, John Dent, who was a partner at Child’s Bank, and in 1790 became Tory M.P. for Lancaster. Some societies would also appoint a Lady Patroness, a keeper of stores, a chaplain, or even a poet or an antiquarian.

Election of New Members, Admission Requirements, Fees

Practical electoral and financial matters are laid out in great detail in the books. These include: eligibility criteria for prospective members, methods of balloting (the system of ‘blackballing’ is characteristic of this age), financial matters- annual subscription, admittance or entry fees, dinner fees, Target (tournament) dinner fees, honorary members entry and dinner fees and any additional general fund (where applicable).

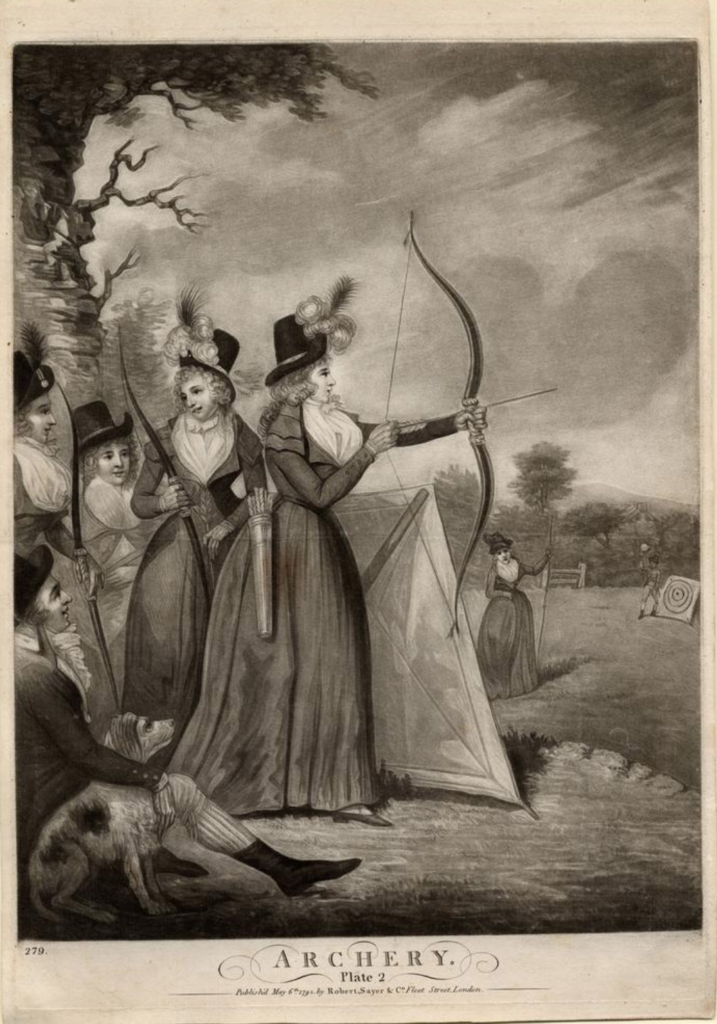

It was a good time to be a lady archer, at least financially; ladies were exempt from all fees, except for fines and, if guests were invited, their costs were always covered by the member-invitee.

A distinction should be made between an honorary member and a guest: a guest is someone who can be invited to a dinner or the society’s ball only, whereas an honorary member is a member that can shoot, take part in tournaments, attend dinners, but cannot take part in meetings or balloting.

Fines

Each society established its own price list system of fines. The most common reasons for fining a member were, for non-attendance during meetings (practice), for non-attendance during target days (tournaments), for turning up late, and for not appearing in appropriate uniform, either for meetings or target days.

On rare occasions, some societies imposed fines for not attending societies’ dinners or the off-season winter meetings, for not wearing or returning medals at meetings, or for shooting out of turn.

Sadly, no records survive to see to see how often or whether the fines were actually imposed. These, like other financial records, were kept in separate ledgers by a treasurer or a secretary.

The make up of the societies

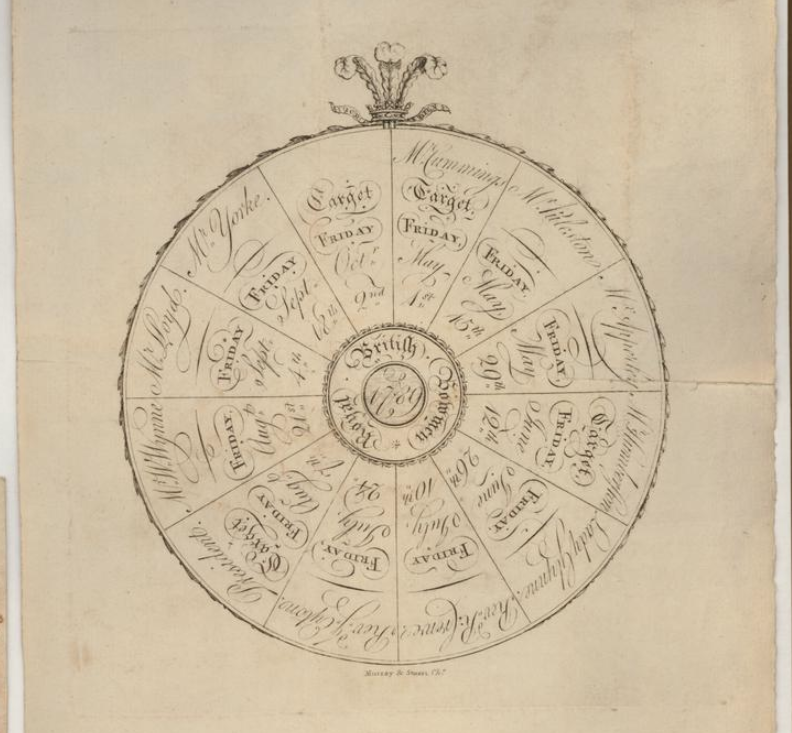

At a first glance, societies like the Royal British Bowmen (est. Feb 27. 1787, Wrexham, North Wales) and the Royal Kentish Bowmen (est. 1785, Dartford, Kent), may seem more exclusive because they operated under royal patronage.

It might be thought that the Prince of Wales’ name would have attracted a greater number of titled members in pursuit of networking, creating another version of a gentlemen’s club, archery taking a backseat.

And that smaller societies such as the Robin Hood’s Bowmen (est. 1787, Holloway, North London), John of Gaunt’s (revived 1788, Lancaster), Broughton Archers or the Eagle Bowmen (est. 1793, London), being smaller in numbers and significant affiliations, would have been focused more on the sport itself.

But it wasn’t as simple as that. In fact, those societies that were not ‘royal’ by affiliation most often sought a much higher number of honorary members. That helped them keep a very limited circle of original members/institutors, who held the authority within the society.

For example, an all-male John of Gaunt’s Bowmen was restricted to 21 resident members (i.e. those living in Lancaster), and placed no restrictions on the number of outsiders. Those honorary outsiders could only be proposed by an existing member- one of the 21 resident members living in Lancaster.

Furthermore, new proposed honorary members had to be endorsed by a quorum of two-thirds of the resident-members. All these rules further support the fact that there was a desire to preserve the core membership and exercise control over those who ‘walk in’.

It is perhaps because of this, that this society failed to attract much interest at all. Records show that in the first year (1788) there were 13 resident and 4 non-resident members, in 1789- no new members, and in 1790 nine joined, but one was expelled.

The lack of subscriptions, even for the cap of 21 resident members is surprising, since it is the only archery society that charged no annual or entry fee. It is also the only recorded expulsion of a member that I have come across so far in my investigations.

The kudos of belonging to an exclusive club is further emphasised by the fact that the uniform description was listed first in the rule book – highlighting the Society’s distinguished history, and it’s most important asset – the coveted jacket. John of Gaunt’s shooting grounds are still used by archers in Lancashire today.

Another society that seems to have a more authoritarian operation is Robin Hood’s Bowmen, for which, sadly, there is no available members list. However, as in the case of the John of Gaunt’s, the tone and the arrangement of the rule book suggests an old-fashioned and hierarchical vision of their role.

For example, in Robin Hood’s, contrary to the common tournament practice of the 18th century of shooting ‘by lot’, and very much in the spirit of the preceding centuries, shooting was done in order of seniority: the previous year’s winner of the competition shot first, then the President, the Vice President and so on.

Moreover, the President held a deciding vote in balloting, and the secretary appointed to the society was not selected by ballot, as in all the other societies, but instead was appointed by his predecessor.

As to the ‘royal’ societies: the Royal Kentish Bowmen (RKB) and the Royal British Bowmen (RBB) both secured their royal patronage in 1789. RKB had 11 original members at its establishment in 1785, and had no titled members during the first four years of its operation.

In 1786, the membership grew to 30 men, and in 1787 to 61. Once the royal patronage was granted, the society saw the numbers double, rising to 123 listed members, which now included men like Viscount Lewisham, the Duke of Leeds, the Duke of Dorset, and a good few Barons, Sirs and MPs – as well as the twelve high ranking military men.

By the end of 1789, the RBB in north Wales had 101 listed members, membership being unrestricted. But the numbers were capped at 120, possibly for practical reasons.

Interestingly enough, 71 of those were marked as ‘original members’, meaning that only 30 joined after gaining royal patronage, thereby discrediting the idea of deliberate inclusion of the royal prince to promote the Society.

It may be that the RKB’s closer proximity to London allowed it to benefit more from royal patronage, whereas RBB was in an entirely different and separate centre of social activity, being geographically distant. Moreover, the RBB was the first society to allow females to participate in all aspects of the activities: shooting, dining, and electing new members.

Ladies constituted nearly half of the members – 46 to 55 men. Upon closer inspection of the records, I found that 77 out of 101 had relatives in the society, mainly spouses.

This society is by far the most progressive of all and was ahead of its time, whilst many of the other societies appear to be novel versions of the gentlemen’s club.

Money matters

A systematic study reveals that of the individuals that constitute these late 18th century archery societies, the following can be said – the fees and fines combined were moderate, and would in no way disturb a gentlemen’s pocket.

For example, at the higher end of expenses, a certain Mr Smith had paid 10 guineas for his annual membership admittance, plus an annual fee of 10 shillings and sixpence for dinners, an additional annual 1 guinea for special dinners after target days, and say incurred a couple of moderate fines, one for being late and one for turning up without appropriate attire.

In such case, his annual bill would amount to roughly £12. To put things in perspective, £12 in 1790 could buy one horse, or was an equivalent of 80 days wage of a skilled tradesman.

It really would not make that much of a difference to Mr Smiths’ wealth, because the wages of the upper-middle class at the close of the 18th century were generally between £700 and £1500 per annum. Income for the upper-classes and the nobility at the time was anything from £1,500 to £12,000, a few receiving as much as £30,000 to £40,000 annually.

On this interpretation, the members of principal archery societies of the period can be said to come almost exclusively from the top 5% of the population, but within that group there was probably a huge disparity of income.

Uniform

If you think strict rules about clothing means ‘no denim jeans’, you may (or may not) be surprised to learnt that things were markedly different in the 18th century.

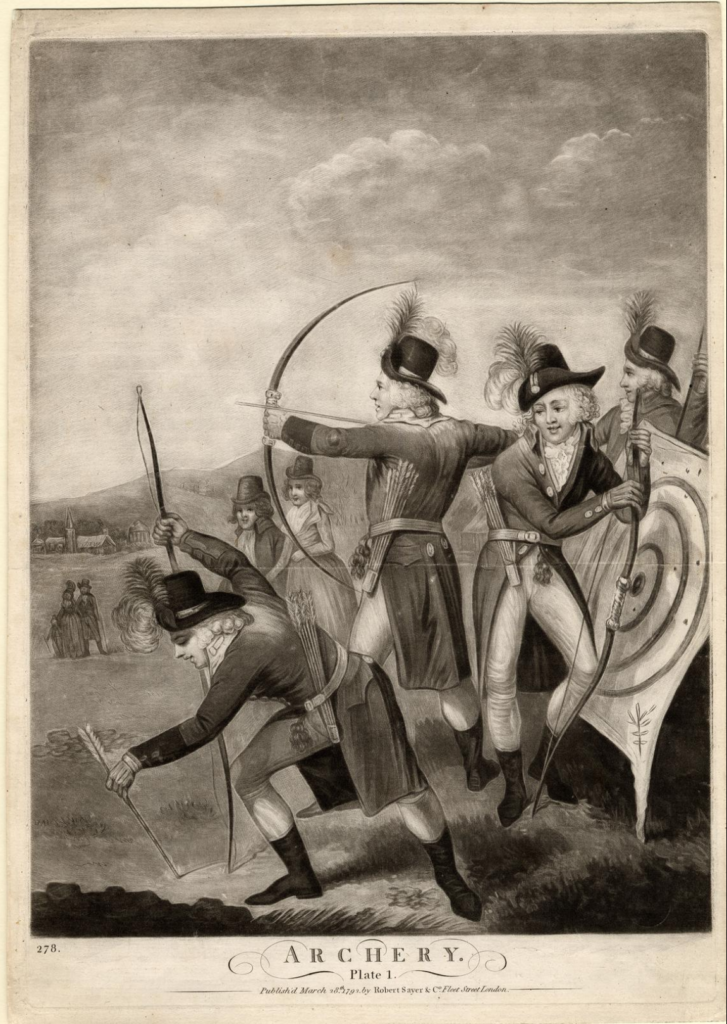

Wearing of the uniform by all members was obligatory and all societies described it in considerable detail – usually before the shooting rules! Every society for which the rule book can be located, adopted a green coat and either buff (light brownish yellow) or white waistcoat and breeches.

The Royal British Bowmen had perhaps one of the simplest descriptions of its uniform, merely requiring it to be “green and buff” for men, and for ladies “green and buff dresses”. The uniforms of the various societies are in fact surprisingly consistent, right down to details such as half boots or Muscovy boots and belts, pouches and tassels.

It was common practice to appoint a clothier to ensure that that each outfit of a society was the same. Both the Royal British Bowmen and the Toxophilite Society specified a particular clothier that members were expected to order from.

The most common differentiating features as described in the rule books were the design of buttons, or the details of a head piece. The Toxophilites have a Prince of Wales button, (royal triple ostrich feather insignia), double gold loop, and black feather; the Royal Surrey Bowmen a gold button and a gold loop and a sprig of box (evergreen tree native to Britain); the Eagle Bowmen, a button and loop and a black ostrich feather; Robin Hood’s Bowmen, a buff hat with a green feather, a society button and a gold loop; John of Gaunt’s merely asked for two feathers, one black and one green.

There were exceptions to the normally strict rules for wearing uniforms, but usually applicable only to clergymen and those in mourning!