Korean archery and how it unfolded. By Robert Neff

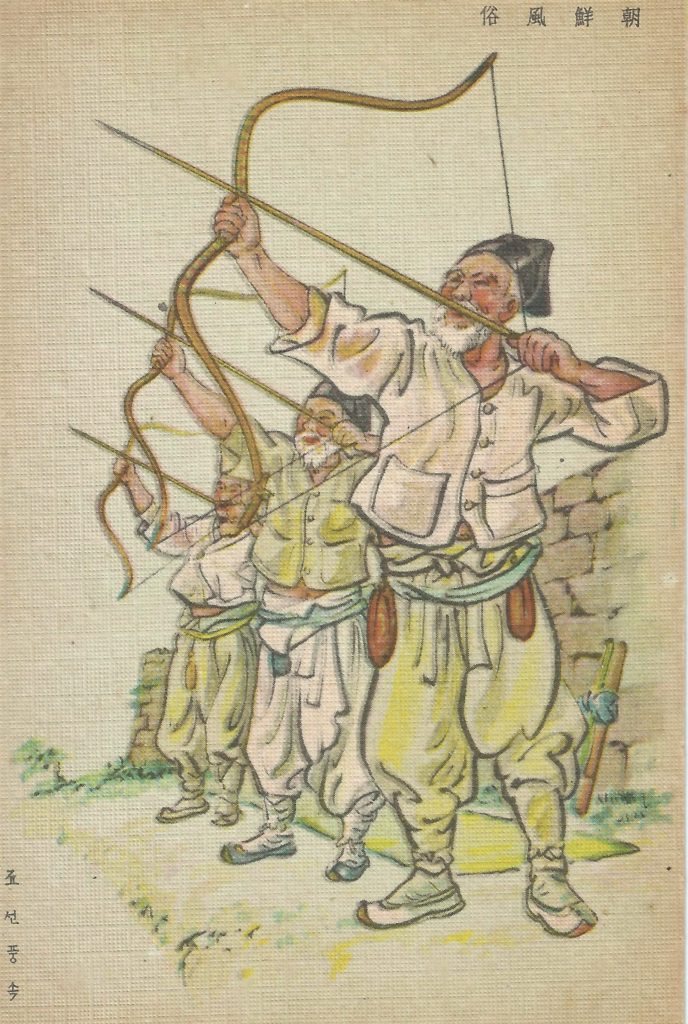

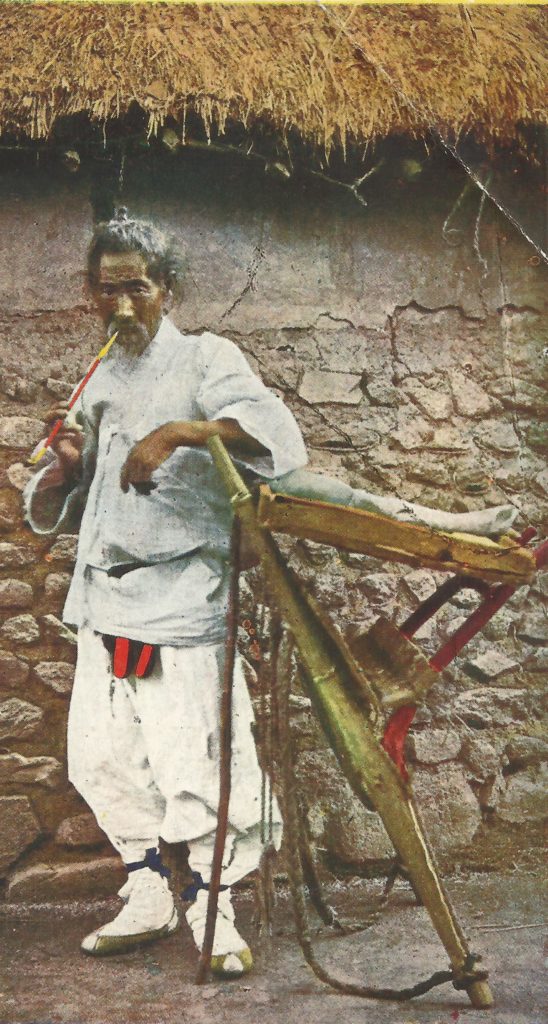

Prior to the introduction of matchlock rifles, the bow was the quintessential Korean weapon – especially the pyeonjeon. The pyeonjeon was, for the most part, an ordinary bow except it utilised a long grooved stick or firing tube called a tonga.

This secret Korean innovation increased the range of the arrows and, because a tonga was needed, made it difficult for the enemy to pick up and reuse the Korean arrows. According to a Korean officer from the early 20th century, the tonga tended to sow deadly confusion amongst the enemy:

“The grooved stick can be seen by the enemy, who thinks that the arrow has not yet been released so that he continues to watch the bowman when suddenly the arrow coming unseen from the sky pierces him.”

During war, women helped construct bows and arrows and, in dire situations, “sometimes helped to ‘man’ the city walls” with small bows that fired 15-inch-long “iron arrows, like a needle, with great force.” In the early 17th century, matchlock rifles were introduced to the Korean peninsula and the bow’s importance on the battlefield waned. Archery, however, remained an integral part of Korean society it was, according to Shin Myung-ho, the author of Joseon Royal Court Culture, “a fundamental aspect of refinement.”

Many of Joseon’s early monarchs were masters of archery. King Jeongjo (r. 1776-1800) frequently demonstrated his prowess with the bow and, according to one source, was “unrivalled by his contemporaries.” While practicing in Suwon, he hit the target 24 out of 25 times.

“The king used a red painted bow made of rhinoceros horn” and shot at a target with a bear’s head painted in the centre of a white background and surrounded by red hemp cloth. Other participants in the competition or practice shot at similar targets, except theirs had a blue border and a painted stag’s head in the centre. “The different targets manifested the Confucian social hierarchy.”

While King Jeongjo may have been “unrivalled by his contemporaries,” he did not compare to his predecessors. In his youth, it wasn’t uncommon for the founder of the Joseon dynasty, King Taejo (r. 1392-1398) to shoot between 50 and 100 arrows and hit the target every time. King Sejo (r. 1455-1468) was also an impressive archer and “was praised as being the ‘reincarnation of Taejo.’”

Of course, not all members of the royal house were as skilled as King Taejo. On June 21, 1908, Prince Uihwa (Yi Gang) was involved in a potentially fatal incident while practising archery. He apparently struck a boy with an arrow but fortunately the wound was not serious and so, according to the local newspaper, Seoul Press, he “gave the unfortunate lad one yen” in compensation – which was about 50 cents.

In the final years of the Joseon dynasty, King Gojong does not seem to have displayed his archery prowess to any of his Western guests – at least none that I could find. However, many Westerners did witness archery events in Seoul and for the most part were very impressed.

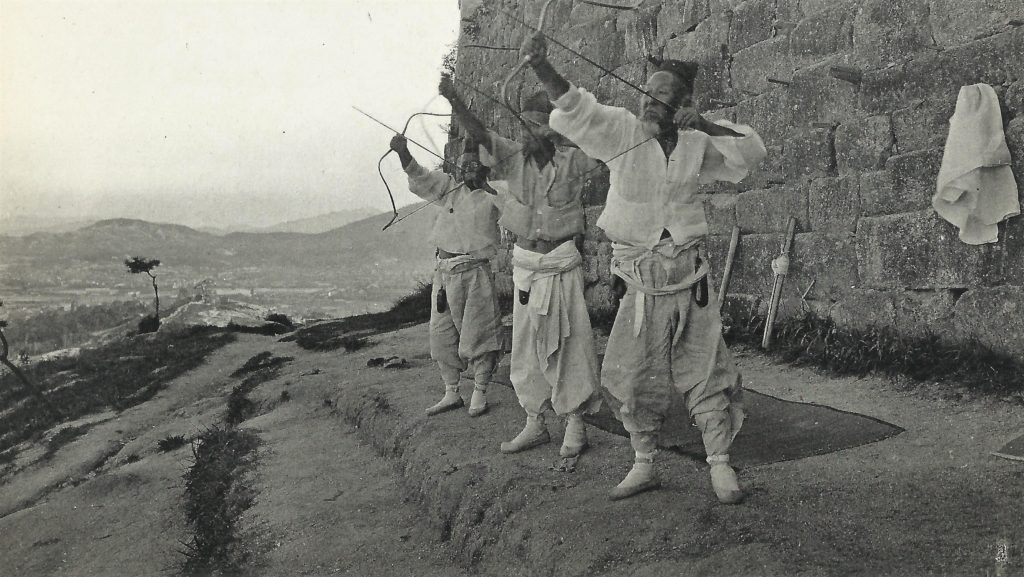

Arnold Henry Savage Landor (better known as Henry A. Savage Landor), an English painter and writer, visited Korea in early 1891 and wrote extensively about his adventures. His writing tended to be self-serving and very opinionated, but amusing. According to him, archery was a noble pastime and one of the few sporting events in Korea: “Princes and nobles indulge in it, and even become dexterous at it. The bows used are very short, about two-and-a-half feet long, and are kept very tight. The arrows are short, and light, generally made of bamboo, or a light cane, and a man with a powerful wrist can send an arrow a considerable distance, and yet hit his target every time.

Nevertheless, the noble’s laziness is, as a rule, so great, that many of this class prefer to see exhibitions of skill by others, rather than have the trouble of taking part in such themselves; professional archers, in consequence, abounding all over the country, and sometimes being kept at the expense of their admirers.

Both the Government and private individuals offer large prizes for skilful archers, who command almost as much admiration as do the famous espadas in the bullfights of Spain. The King, of course, keeps the pick of these men to himself; they are kept in constant training and frequently display their skill before his Majesty and the Court.”

Fortunately for Landor, the Korean archers he encountered were as skilled as King Taejo. One evening, as the sun was setting, he inadvertently walked onto a target range near the East Gate. With the sun in his eyes and unable to see, he heard Korean soldiers shouting at him to stop but he continued on – convinced they were having fun at his expense. He later wrote:

“I made a step forward, but hardly had I done so when a noise like a rocket going past was heard, and a bunch of arrows became deeply planted in the earth, at a white circular spot marked on it, only about two yards in front of me. I counted them. They were ten in number. My danger, however, was, after all, practically no account, for these archers, as I found out by repeated observation of them, hardly ever miss their target.”

In the early 1890s, American ethnographer Stewart Culin wrote an extensive account about Korean archery. According to him, Seoul was divided up into four different quarters or sections and had their own archery teams composed of Han-ryang. Culin described the Han-ryang as “‘leisure,’ or ‘unoccupied fellows,’ not in service, being neither nobles nor soldiers. They do no work, but travel from place to place, and are said to think and talk of nothing but arrow-shoot from morning until night.”

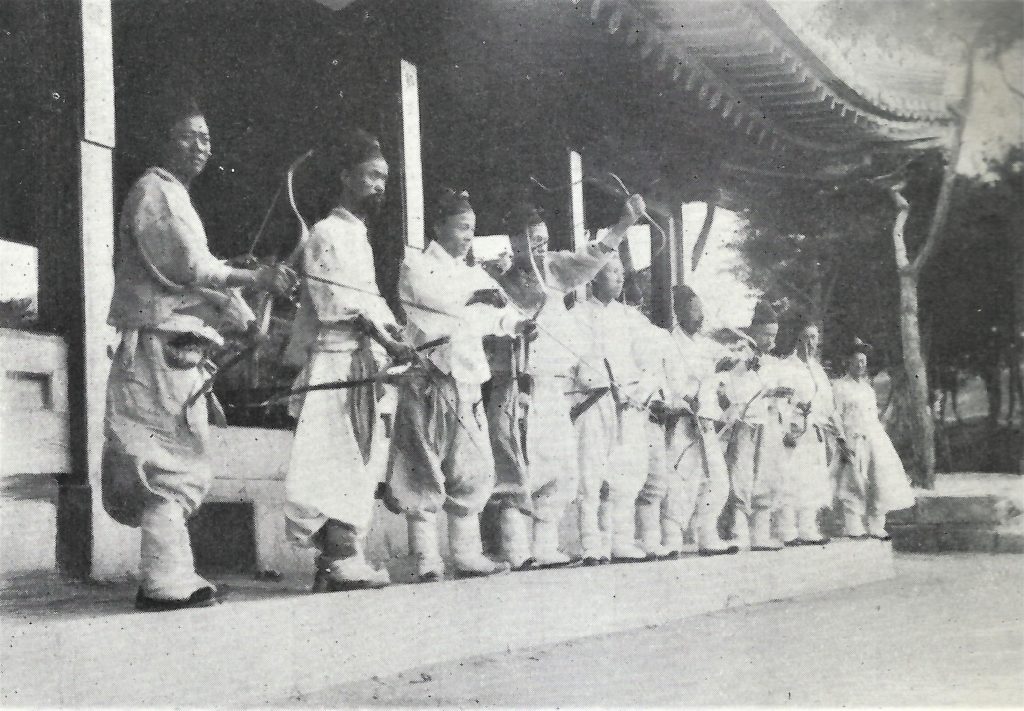

The four archery teams of Seoul were the Eastern, represented by a green banner; the Western, by a white banner; the Northern, represented by an azure banner and generally recruited from the noble boys; and the Southern, represented by a red banner, recruited from the sons of military families.

For the archery contests, each team consisted of the 12 best archers – all dressed alike and wore arm-bands. The target was a large board with a black square painted in the centre. Each of the players would have three turns in which they fired five arrows – for a total of 15 arrows. An arrow that struck the board earned one point while those that hit the black square earned two points.

The teams even had their own cheerleading squads. According to Culin:

“Sometimes four singing girls, [Gisaeng], for each of the four different sides, accompany the shooters, and when a hit is made the girls for that side sings, calling out the name of the person making the shot. The music at the same time strikes up.”

At the end of the day, when the contest was finished, the musicians would go to the victors and the losers would follow. A great feast would be held, presumably with vast amounts of alcohol and singing, all paid for by the losers.

Not all of these competitions were large events – sometimes they were just friendly competitions between four or five men who would each pitch in a small amount of money and the winner was awarded the pot.

Men were not the only ones to compete. Boys, armed with steep-pointed arrows, played a game involving their shoes:

“A mark is put in the ground at a certain distance and those who engage shoot at it. The one who goes farthest away must put his shoe in the place where his arrow strikes, and then all shoot at the shoe, including its owner, until one misses, when he must put his shoe down instead.”

Culin concluded his description of the game by noting it was “very destructive to boys’ shoes.”

By the mid-1890s, time was running out for the Han-ryang and their old customs and traditions. Although they were “a fraternal union, helping each other in trouble,” it was their retention of old customs and traditions that ran afoul with King Gojong’s reforms.

According to Culin, the Han-ryang “go about always carrying their bow and arrows, indifferent to public opinion, and doing whatever they please. During the past four years His Majesty, the King, has suppressed the Han-ryang, subjecting them to severe penalties, and it is said that in a few years they will entirely disappear.”

Yet, despite Culin’s fears, the Han-ryang flourished and continued to impress Westerners visiting or residing in Korea.

Burton Holmes, an American travel writer, visited Seoul at the end of the 19th century and spent “an interesting hour watching the gentlemen of Seoul contending in friendly rivalry in the dignified and medieval exercise” of archery. He described the archery range that had recently been established.

“The Archery Range is excellent; a temple-terrace for the archers, the target on a terraced hillside, beyond a broad green-clad depression where passers-by may walk in safety beneath the high curvings of the feathered shafts, for the Korean gentlemen aim high, as if intent on hitting unseen stars. And they are accurate of aim; for nearly every arrow as it descends from the cleft skies strikes the mark or, at the worst, falls very near it.”

By 1903, there were five archery teams in Seoul and in a large tournament held in October, 75 men (15 from each team) competed. As in the past, the winning team paid nothing for the large feast that followed the tournament.

William Franklin Sands (an American advisor to the Korean government from 1899-1904) was very impressed with Korean archery and wrote: “The bows were shorter than ours, or than the old English bows, but much heavier and broader. They were made of wide strips of ox horn cunningly welded together and were more powerful than ours. I could not even bend one, though the Koreans who practised constantly could send their yard-long reed shafts tipped with iron very accurately and with incredible rapidity and strength.”

According to Sands, the Korean archers never hesitated to engage in “target competition against a .45 Colt revolver at a hundred yards” and he had personally witnessed them make “a series of bull’s eyes at two hundred and even make a target at three hundred yards.”

It is a shame Sands did not arrange a little competition between Smith F. Phillips – an American engineer working on the Seoul-Chemulpo Railroad – and some of the archers. Phillips was a huge man and described in the local newspaper as “one of those gentlemen you can see with the naked eye.” Not only was he big but he was also famous for his skill with the .45 Colt – able to “shoot the head off a flying bird without seeming to aim.”

While Phillips may have been famous with his American peers, to his Korean hosts, he was notorious; he liked to shoot the top-knots off of Korean labourers as they worked – up to 100 yards away. Apparently Phillips “had only been afraid of getting out of practice” but when confronted by Sands he “was perfectly reasonable” and agreed to stop!

All pictures from the Robert Neff Collection