Kristina Dolgilevica looks at a revised edition of the standard English reference work.

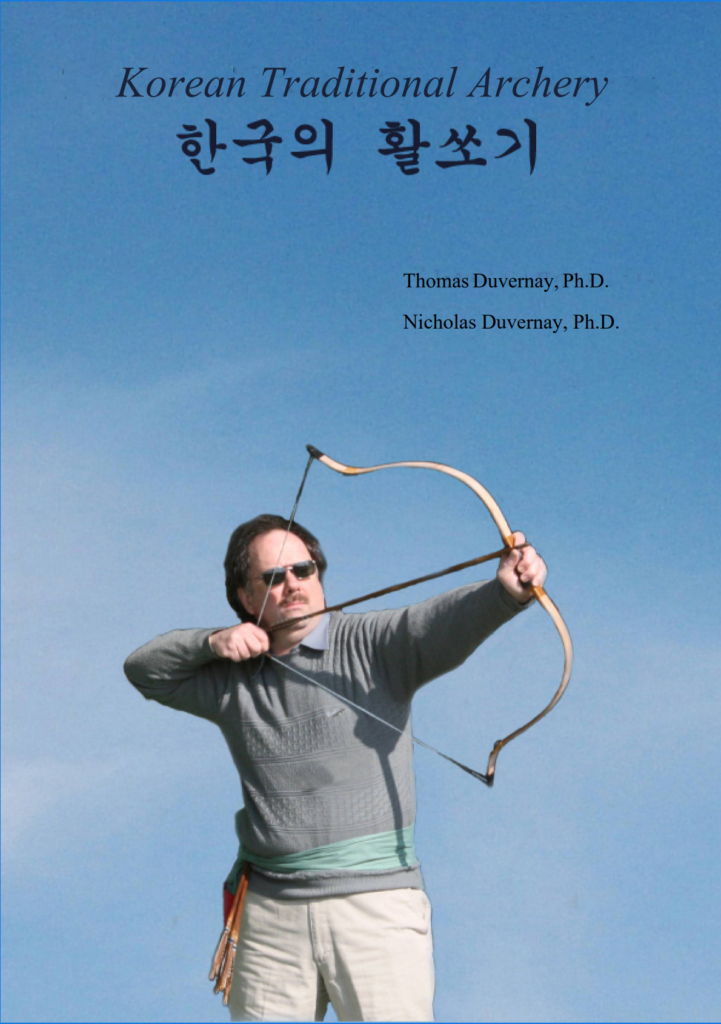

Professor of Korean studies Thomas Duvernay, a long-standing archer and one of the authoritative figures on the subject, has revised and released his Korean Traditional Archery book this year. The original was published in 2007 and has since been revised; this latest edition is the product of a partnership with his son, Nicholas Duvernay, who has a PhD in applied linguistics.

Thomas Duvernay’s book was the first exhaustive body of work about Korean traditional archery (KTA) in the English language and, in the tradition of true scholarship, he intends to continue to revise it, addressing the ‘unanswered’ and newly emerging questions.

Overview

This scrupulously researched book is not a handbook or a ‘how-to’ manual – it has more of an encyclopaedic character. It captures both the modern and the ancient spirits of the practice of archery and its culture. This book will be enjoyed by many, but to quote the author, it is indeed “an ideal book for those who aspire to become proficient in KTA”.

The printed book comes in colour and black-and-white editions, is well signposted, illustrated throughout and has multiple appendices and a glossary. The writing is clear and uncluttered, the layout easy on the eye. While the image resolution may not be the sharpest, due to the age of many of the photos, I have not had any issues understanding them.

Content

The book is conveniently divided into six chapters, dealing with the history of Korean archery, equipment, technique, archery grounds/clubhouse rules, competition, and philosophy and etiquette. The appendices provide a handy shortcut to terminology and cover a wide range of subjects, from the rules of competition to archer, bow and accessory terminology in Korean, English and Chinese.

An archer or coach will most likely flick straight to chapter three, on technique. Duvernay has dedicated less space to shooting technique compared with other subjects; perhaps rightly so, given the many regional schools of shooting in Korea. Nevertheless, the basics are well presented and described, and will be of use to both the novice and the more experienced traditional archer.

Most Western KTA archers have limited sources of information available to them, and perhaps no access to coaching, and will typically share and discuss the specifics on online forums. The content of this book covers and explains the most contentious subjects discussed in those online entries, such as the thumb ring types and their use, arrow handling, bow balance, nocking point position, bow stringing and so on. It deals with the issues relevant to these archers in an accessible and affordable form.

In practical terms, the chapters dealing with the clubhouse rules, archery grounds and competition may be less relevant to the Western reader, since as yet there are no traditionally run clubhouses outside Korea. However, they offer a fascinating insight into the discipline; the content is highly informative and relevant to comparative studies as well as your own scholarly pursuits.

About a third of the book, and the most fascinating part, is its second chapter, dedicated to the equipment. Archers, coaches, historians and bowmakers will revel in the wealth of information about the bows, the arrows, the rings and the strings, and will doubtless revisit this chapter the most.

Conclusion

As a historian, a KTA archer and an archery coach, I tend to be selective with non-fiction books, and not to read them from cover to cover. This work, however, was an exception. Though I was tempted to go straight to the technical chapter, I started from page one, as the author had clearly set out a logical sequence ending in a ‘conclusion’, and I wanted to get to that conclusion via the route intended. An indispensable book for your archery library.