On the 606th anniversary of archery’s greatest military victory, Kristina Dolgilevica reconsiders the Hundred Years’ War and asks, was Agincourt a success?

The significance of a battle can be judged upon two criteria: first, its internal strategy and tactics, and the brilliance – or stupidity – of its commanders; and, second, how its outcome affected the war of which it was a part and, going forward, the course of history.

As great battles recede into the past, the academic historian – whose function it is to analyse their significance – like everyone else, becomes more and more desensitised to the human suffering of the individual participants, and the terrible consequences for societies.

If, in retrospect, we can divorce the great battles of the past from emotion, we should be able to arrive at more reliable conclusions about their historical importance.

If I asked you to name some important battles from the past, your list might include the Battle of Britain, Waterloo, Stalingrad, Balaclava and the Charge of the Light Brigade, Midway, the Somme and, almost inevitably, Agincourt. The fact that this last battle took place four centuries before any of the others on that list speaks volumes for its prestige in the catalogue of slaughters.

Most of those battles have been amply commemorated, glorified or otherwise modified or popularised using the medium of literature or film. In fact, such conflicts were exploited long before the advent of film by those reading sermons from their pulpits, in the verse and prose of Shakespeare or Tennyson, to name but two, and again in the literature of the 19th century, from Tolstoy’s War and Peace to Edward Creasy’s Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World (1851).

It is interesting to note that in the latter, an authoritative and erudite English historian highlighted the Siege of Orleans, Joan of Arc’s campaign against the English, not Agincourt, as the most important battle of the Hundred Years’ War period.

In the case of Waterloo, it was a clear defeat of Napoleon, which ended 20 years of anxiety in Europe; the Battle of Britain probably prevented an early Allied collapse and the total fulfilment of Hitler’s ambitions, while Stalingrad delivered a death blow to Hitler’s ambitions in the east and changed the course of World War II. But what is the historical significance of Agincourt?

The Hundred Years’ War: Rationale

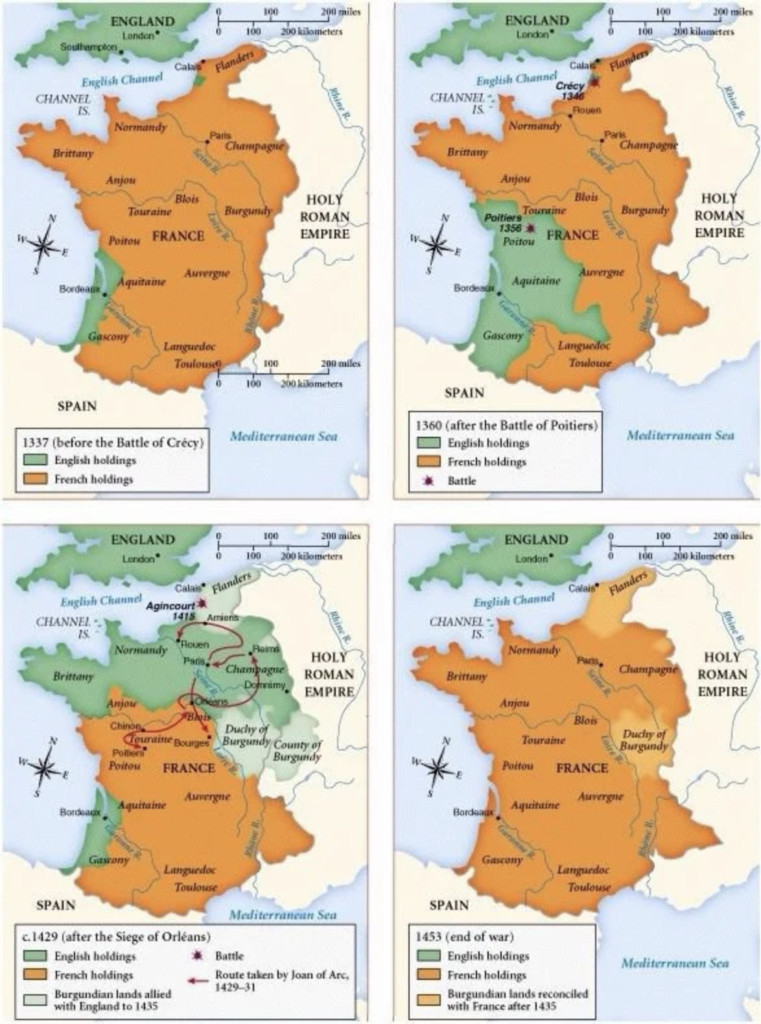

The Hundred Years’ War was not even regarded as a unitary conflict until the 19th century, when historians gave that name to the period of sporadic hostilities between the two kingdoms, England and France, which lasted for 116 years, between 1337 and 1453. The fight between the two royal dynasties was for the French throne and French land. Among the English successes, the most famous are the Battles of Crécy, Poitiers and Agincourt.

These battles are better remembered – and, indeed, celebrated – in England than in France, for the simple reasons that they resulted in English victories. Crécy and Agincourt are particularly hailed for the superiority of the English longbow, its might and power in penetrating the French armour. Historians tend to dramatise this aspect almost as much as popular culture.

However, none of these battles had a decisive effect on the course of hostilities. Moreover, any territorial gains made by England were quickly reversed by the French when the English withdrew. You might say these names survive in memory for the very reason that they were the sole important English victories in that entire century of conflict.

Origins of the Conflict

The rationale behind the Hundred Years’ War was in large part the territorial ambitions of England. When William the Conqueror ascended the English throne in 1066, he was already Duke of Normandy and, when his great-grandson Henry II inherited the dukedom of Anjou from his father, the English kings became the most powerful vassals to the French king. Firmly based on the territory of western Europe, they controlled not only England but large areas of northern France.

However, in 1204, King John lost Normandy and Anjou to France, leaving the Crown with only limited control over Gascony. These losses caused further resentment. Northern France, as well as being fertile and productive, was most importantly the gateway to mainland Europe and its well-established trade routes. Thus, disputes and claims continued into the next century.

Edward III vs France

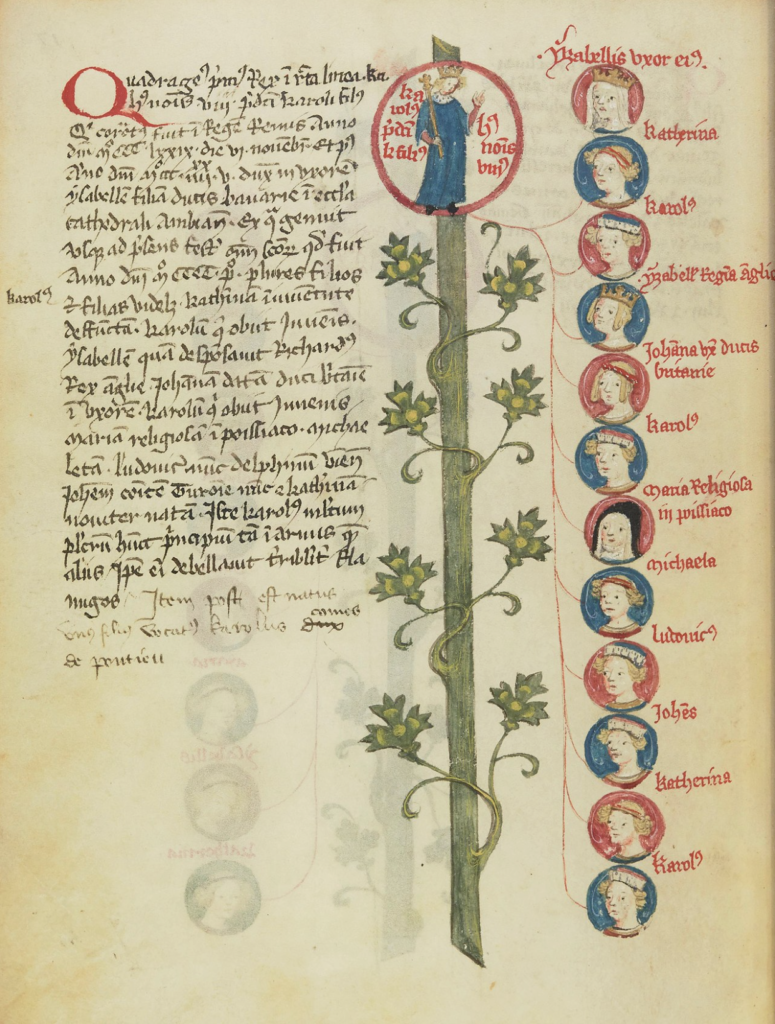

Edward III, crowned King of England in 1327, put forward his claim for the title of the King of France. Edward’s mother, Isabella, was sister to France’s Charles IV and daughter of Philip IV, which gave him a technical claim to the French throne. However, it was the son of Philip’s younger brother, Philip VI of the House of Valois, who succeeded. To add insult to injury, Philip VI confiscated Aquitaine from the English in 1337, a catalyst for the Hundred Years’ War.

In 1340, Edward III started formally to call himself ‘King of France and the French Royal Arms’ and began to seek alliances with disaffected French nobles; he also began to make organised raids, chevauchées, into French territory. These were often successful.

At Crécy, in 1346, a French attack upon the English forces was repulsed with significant French losses, and the strategically important port of Calais was captured by the English. Another successful campaign followed, culminating 10 years later in a victory at Poitiers, led by Edward’s son, Edward the Black Prince, in which King John II (The Good) was taken prisoner. This victory is again often attributed to the superiority of the English longbow.

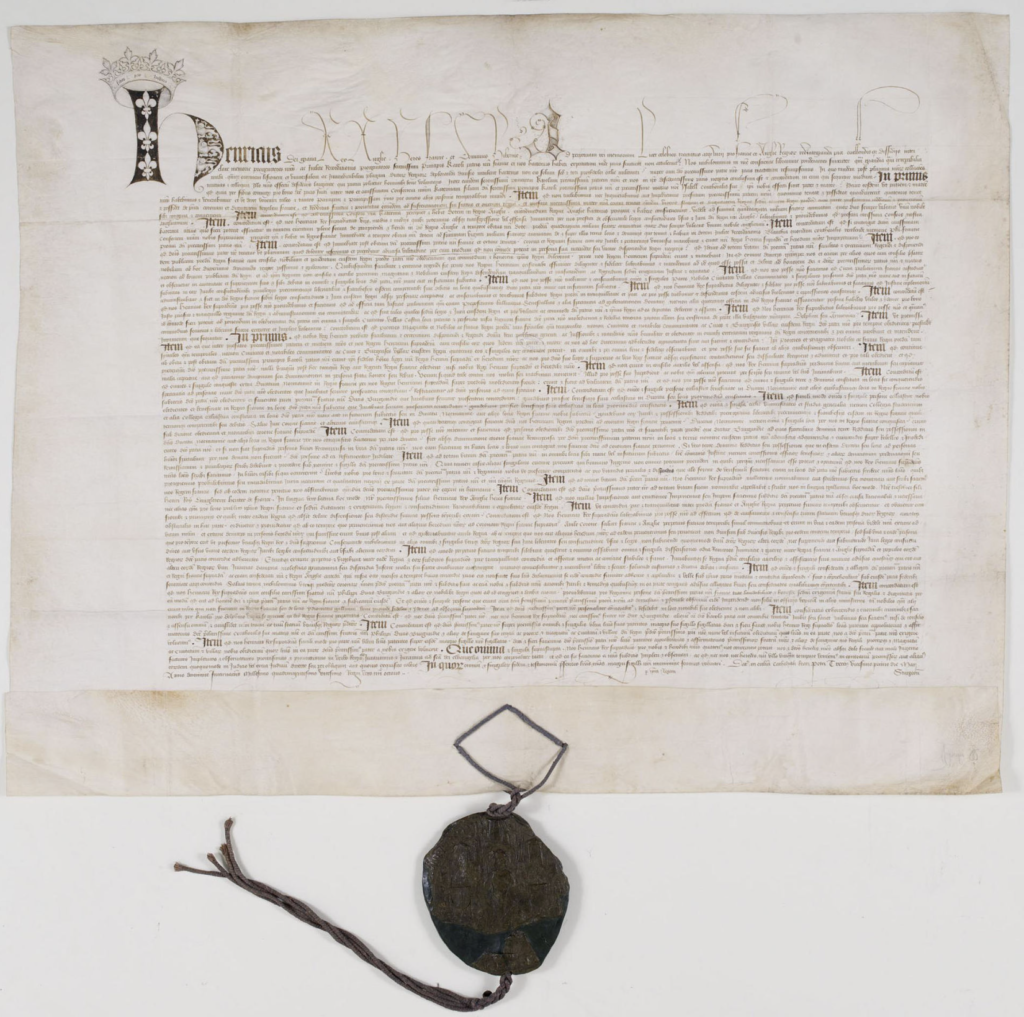

Edward had intended to demand that he be crowned officially King of France but, after the capture of John, a ransom agreement was reached and formalised by the Treaty of Brétigny of 1360. Under its terms, Edward would renounce his claim to the French throne and return the prisoner, and in return France would pay him three million gold crowns and cede extensive territories in north-western France to England. The Treaty represented a huge loss for France but it did at least usher in a short period of peace.

The next phase of the war, which recommenced in 1369, was longer and clearly the English victory at Agincourt (Azincourt) in 1415 was one of the most important events – for England, at least. In fact, its significance has been exaggerated by two factors: the disparity in the sizes of the opposing forces and the fact that it came after a dearth of English victories.

By this time, the English were advantaged by internal struggles within France. Two major royal houses, the Orléans and the Burgundians, were now in conflict with the French Crown in an attempt to wrest control from the next legitimate successor, the insane Charles VI.

The Battle of Agincourt

Henry V led his force of about 12,000 men into France to besiege Harfleur, an important coastal port city in Normandy lost by King John in 1204. The choice of this location was not merely a question of convenience. Most importantly, it was a political statement and a show of commitment to his Burgundian allies.

However, Harfleur put up stout resistance and Henry lost several thousand men in taking it back. By the time his army headed back to the port of Calais, many were suffering from exhaustion, dysentery and other sicknesses. Then his passage to Calais was blocked by French defences on the Somme, forcing him to take a detour and allowing the French to amass a force of some 20,000 men to oppose his roughly 6,000.

Estimates of these numbers have varied wildly and are the subject of dispute; some recent research conducted by social historians say there were probably around 8,000 with Henry, and about 10,000 to 12,000 on the French side. Latest research also downplays the role dysentery played in the conflict.

The battle took place at Agincourt, about 40 miles inland, chosen by the French. Though outnumbered, the English had the advantage of the ground and were more coordinated. Their army was composed of three archers to every one man-at-arms. The French cavalry was forced to advance over boggy, tiring ground towards an army defended by sharpened stakes buried in the ground.

Anne Curry, Professor of Medieval History at University of Southampton, has found evidence in the English archives that suggests the English had captured the French battle plans and knew how to exploit fully the narrowness of the field of battle. Predictably, at home, the victory was hailed as little short of miraculous and its glorification through songs and ballads began even before Henry’s return to London. The Agincourt myth was born.

Aftermath and Effect

Arguably, internal conflicts in France now presented a greater threat than the English incursions. The Armagnacs and the Burgundians were vying for power, while many French towns were ruined and in need of rebuilding after so many years of conflict. Taking advantage of this, Henry V mounted a new campaign in 1417, which culminated in the capture of Rouen two years later, and was subsequently planning an assault on Paris, assured of its success.

However, following the assassination of John, Duke of Burgundy, by the rival Armagnacs, John’s son, Philip, sided with the English and negotiated the Treaty of Troyes (1420), under the terms of which Henry would act as Prince Regent to the insane Charles VI until his death, and would then marry his daughter, Catherine, thus becoming the heir to the French Throne. These terms were accepted in northern France but rejected in the south.

Henry and Catherine had a son, later Henry VI of England, who at the age of nine months – after the death of both Henry V and Charles VI in 1422 – was officially recognised in Paris as the King of France.

His reign did not last, however, as the Armagnacs, headed by Joan of Arc, reclaimed France for the French in 1428. From that time until the end of the conflict in 1453, the tables had turned for the English, who had lost eight consecutive battles against the French and all their territorial gains.

Thus, in the overall scheme of things, the ‘great victories’ of the English in France were in fact only localised and temporary successes, and France retained its independent integrity. The strategy had failed: the land gained had all been lost and the claims to the French throne had come to nothing. England had lost the use of the port of Calais, and with it the economic advantages of trade with Europe.

Moreover, in the immediate wake of the conflict, England itself was seized with internal wars for the Crown between the Houses of York and Lancaster – the War of the Roses – resulting in the loss of both male lines to the English throne, and in the new House of Tudor claiming power for Henry VII.

Historical Reservations

The key to attaining a clear vision of the Hundred Years’ War, and the battles that it comprised, is to attempt to see things in the correct proportions, through a timeline. There are around 60 documented battles in the period, mostly small scale. About half of those can be recorded as English successes and half as French successes. The English victories occurred mainly before Agincourt and, though English territorial holdings immediately following Agincourt were substantial, they were also short-lived.

The French wins were mostly concentrated from the Siege of Orléans in 1428. The French swiftly regained control over their lands, learned from their mistakes and launched aggressive and tactically innovative campaigns. The decline of the French feudal lords, with their outdated ideas, had a beneficial effect on the composition of their armies. Their use of progressive and new weaponry were the most decisive factors in pushing out the English.

This modernisation of warfare was perfectly exemplified by the final battle of the conflict, the Battle of Castillon (1453), the first European battle won by the use of cannon. In short, the victory of Agincourt, though decisive and impressive, was a victory only to itself, in a war that was ultimately lost.

In analysing any war or conflict, from any historical period or event, a historian needs to be constantly aware of the distorting factors. First, the paucity of facts and the unreliability of documentary evidence and hearsay. Secondly, their own prejudices.

It is always tempting to see wars as a series of battles, because battles by their very nature attract most reportage as exciting manifestations of the conflict. The mundane political and financial considerations behind their initiations and support often tend to be neglected. The abundance of evidence, often contradictory, leaves ample room for speculation. Hence the adage: “Histories tend to be written in favour of those who write them.”