Many countries in the world have archers and archery as part of their personal folklore. The bow and arrow has been the protector of the nation for countries as far apart as England and Bhutan. The long association with rugged individualism and skill – and frequently, cunning – has been irresistible to mythmakers and storytellers forever; it is almost an essential part of the human condition.

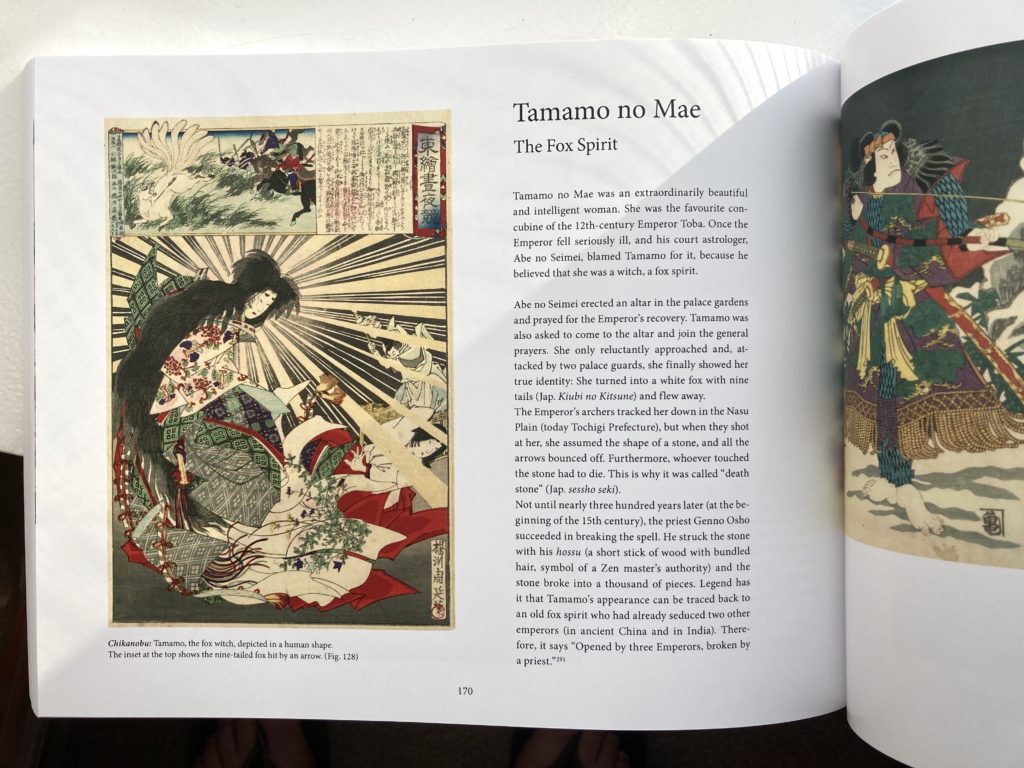

However, few places entwine archery, history and culture like Japan. As well as the usual roles of hunting animals and defeating enemies, the bow plays a more magical role in mythology when children are born, demons need to be cast out, and good harvests secured, amongst much else. The bow even becomes a kind of communicator between the gods and man, a talisman that can predict the future. (It plays a similar role in Indian mythology too.)

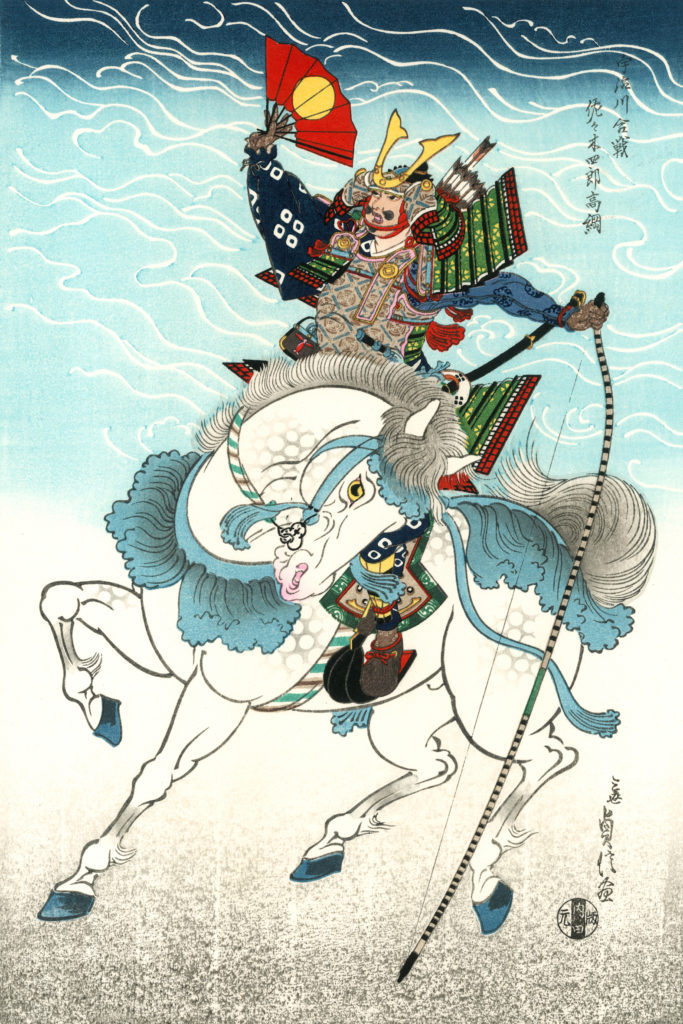

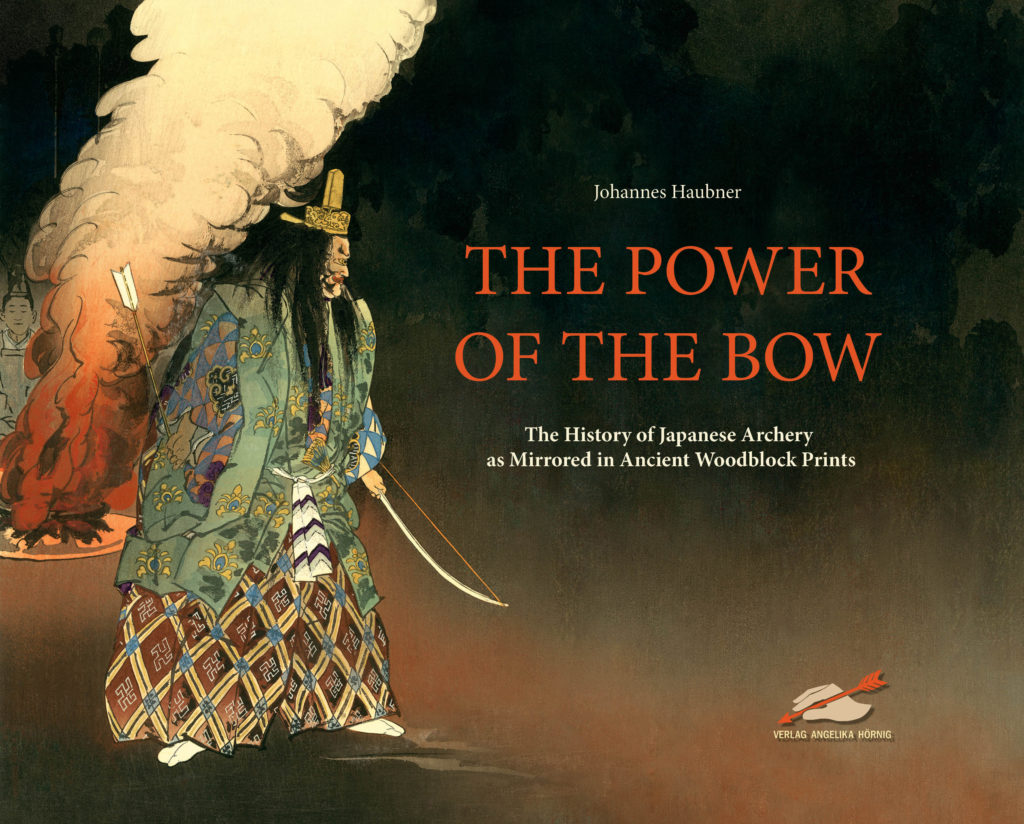

Johannes Haubner’s The Power Of The Bow is an English translation of a book published a few years ago in German as ‘Die Macht des Bogens’, and a product of the archery specialist publishing house Verlag Angelika Hörnig, who focus on the traditional and historical sides of the sport. The book tells the story of historical Japanese archers through 190 traditional woodblock prints, mostly in the genre known as ukiyo-e, which roughly translates as ‘pictures of the floating world’. This genre peaked in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, when the best-known works, like Hokusai’s ‘The Great Wave’ were produced, and began to influence art all over the world.

Despite their distinctive ‘Japaneseness’, the flat, colourful and complex patterning of ukiyo-e is in sharp contrast to most Japanese aesthetics, and they were seen as works for ‘the people’ rather than the nobility they often depicted.

This book takes us on a wild ride through history and mythology. Bow rituals, competitions and ceremonies are depicted, legendary archers are portrayed and their exploits are told, and along the way the reader also gets a thorough grounding in the influence of Shintoism, Taoism, Buddhism and Confucianism on Japanese archery, and much else besides. Indeed, the book works as a jumping off point for all kinds of Japanese culture.

Possibly the best known character in the west is the samurai Nasu no Yoichi Munetaka, who lived in the 12th century and fought for the Minamoto clan. He is best known for having shot down a fan placed on top of a pole on an enemy ship as a dare; he supposedly achieved this with a single arrow, aged only 16, and shooting from another moving ship. (I didn’t know the second part of the story, where he also shot a warrior on the enemy boat in the neck for having the temerity to dance in ‘a burst of enthusiasm’.) The impudence and skill of Yoichi, an historical figure who eventually became a Buddhist monk, means he remains a popular figure in Japan (he is essentially the Japanese analogue of Robin Hood.)

“Tametomo sinks a ship.”

But he is just one of dozens of interesting figures in here. You can learn about Yuriwaka Daijin, the ‘Japanese Odysseus’ whose tantalising story may show evidence of Western tales influencing Japanese culture, and (extensively) about Minamoto no Tametono, another 12th century man-about-town who was said to be the most skilled archer of all, and led an eventful life and death – a plate here shows him catching arrows with his teeth.

There are multiple asides in this book, with a particularly fascinating section on the various history of archery schools in Japan. One of the most interesting titbits concerns archery in the entertainment districts during the Edo period (17th to 19th centuries), where archery grounds were often found near to temples and shrines. Women known as yaba onna (lit. ‘archery range women’) called over passers-by to try their luck, using short indoor bows known as ko-yumi, rather like you might get at a fairground today.

Small prizes were on offer. You could just enjoy a cup of tea while watching the ladies and their shooting skills, but frequently, the women offered something else apart from just a have-a-go. As the book wryly notes “This is why the expression ‘to shoot an arrow’ is quite ambiguous in 19th century Japan.”

The book is rich in anecdote, full of interesting asides and details and containing a great amount of colourful detail as well as the beautiful prints, many of which are from the personal collection of the author. This is a exceptionally well produced item, and one to add to wish lists and present lists. Rarely does an archery book look like it would make a good birthday or Christmas gift; but this one absolutely would. An illustrated reader for all archers – and indeed, anyone interested in Japanese culture or history.

More at bogenschiessen.de

UHHH, maybe you should change the name of the link to the correct one https://www.bogenschiessen.de/

bogenschEIssen litteraly means to shit bows ;-).

While this is a very common typo in German and a funny one in this case,it leads into the net Nirvana… and not the intended page.

Susan

Whoops! Oh dear. Thank you Susan. Have now fixed.