Kristina Dolgilevica dives into the Eastern past.

Most Russians don’t realise how much archery is in their culture. It is only when it is pointed out to them, that they realise practically all their fairy-tale princes and ‘fools’ are usually either on a horse or shoot a bow.

Countless old songs and sayings refer to bows and arrows, from bylinas to wedding rituals. Russian folklore is filled with references to the ‘noble weapon’. Here are just a few glimpses into the ‘legendary’, the ‘fantastical’ and the ‘real’ in ancient Russian culture.

Bylina

Bylina (Rus. “былина”), literally translates as “something that was”. It is the name for traditional ancient Russian poems loosely based on historical fact. Social life and ritual played a big role in the formation of those bylinas, which were passed down orally from one generation to another.

Most Russian folklorists believe the genre originated during the 10th-11th century, though they argue about its birthplace and categorisation. These narratives contain a curious mix of ancient and more modern Russian folk stories, epic songs, legends and actual historical events and figures.

A more convenient way to categorise them is by content, such as heroic, fairy-tale, novella and ballad archetypes. All of these texts were only written down and collected in the 17th century.

It is clear from their structure that they were intended to be sung, much like Nordic folk tales. One of the most fascinating examples of this ‘mix’ of fact and fiction is the heroic tales or sagas of the three epic knights – The Three Bogatyrs.

Three Strongmen From Rus’

In these semi-legendary tales, the most recurrent type is the horseback warrior, armed with a bow, a sword, and a shield. There are no more famous figures than these three, Ilya Muromets, Dobrynya Nikitich, and Alyosha Popovitch.

All three possess superhuman physical strength, wisdom and courage. Their foes are just the opposite, often resorting to magical powers, lies, and tricks. They are cowardly, ugly and fraudulent.

In these tales, both mythical beasts and human-like nemeses possess certain features (e.g. hair, beards, clothing, etc.) that point directly to the actual people that Rus’ warriors were fighting at the time (10-13th. centuries) – features typical to Finno-Ugric or Mongol tribes. Hence folklorists date most bylinas to that period.

The first and favourite epic hero, Ilya, the son of a farmer from Murom city, possessed phenomenal physical and spiritual powers, and was known as an archer of great skill. His personage is on one hand closely associated with that of an actual medieval knight who became a monk later in his life.

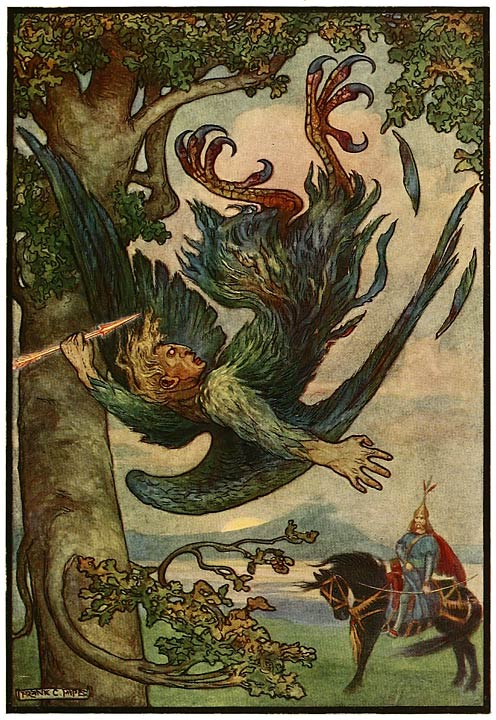

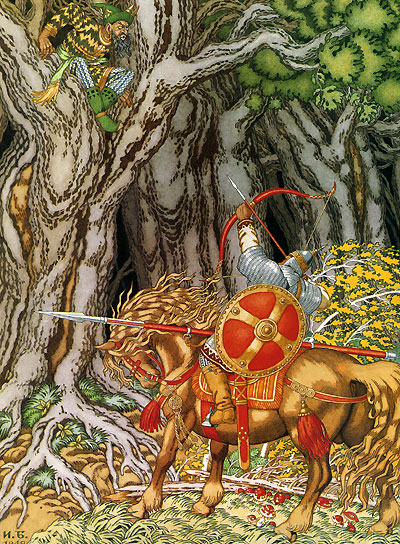

The legend has it that Ilya Muromets was paralysed until the age of 33, when a miraculous passer-by cured him and invested him with great strength. Subsequently he is able to defeat the most dangerous beasts, like the anthropomorphic Solovey Razboynik (Nightingale the Robber).

This half-man half-bird brigand kills and robs his victims by the use of an abnormally loud whistle. His whistling was so powerful that it could not only kill people, but also demolish buildings! Ilya withstood the loud noise, shot an arrow through the monster’s eye and later, in an empty field, decapitated it.

If you travel to Kyiv today, you will find the relics of ‘Saint Ilya Muromets’ in the nearby Kievo-Pechersky monastery. Another prototype of Ilya is an actual warrior monk, sainted in the 17th century – the Venerable Ilya Pechersky. Perhaps it is no coincidence that Ilya Muromets is sometimes also considered analogous with Jesus, who had died at 33 to be reborn.

Canonical Orthodox Christian influence on Russian bylinas is common, especially in the use of the numbers 33, and 3 (Holy Trinity etc.,) and all things ‘wicked and unnatural’, like the magical powers, that most epic heroes are not invested with.

The second epic hero, Dobdynya, (Добрый; meaning ‘good’, ‘kind’, ‘noble’), is considered to have an immediate connection to an actual warlord, Prince Vladimir. He was a highly educated noble warrior and a professional archer. His character is most remembered for slaying the Three-headed Dragon (Tryohglaviy Zmey).

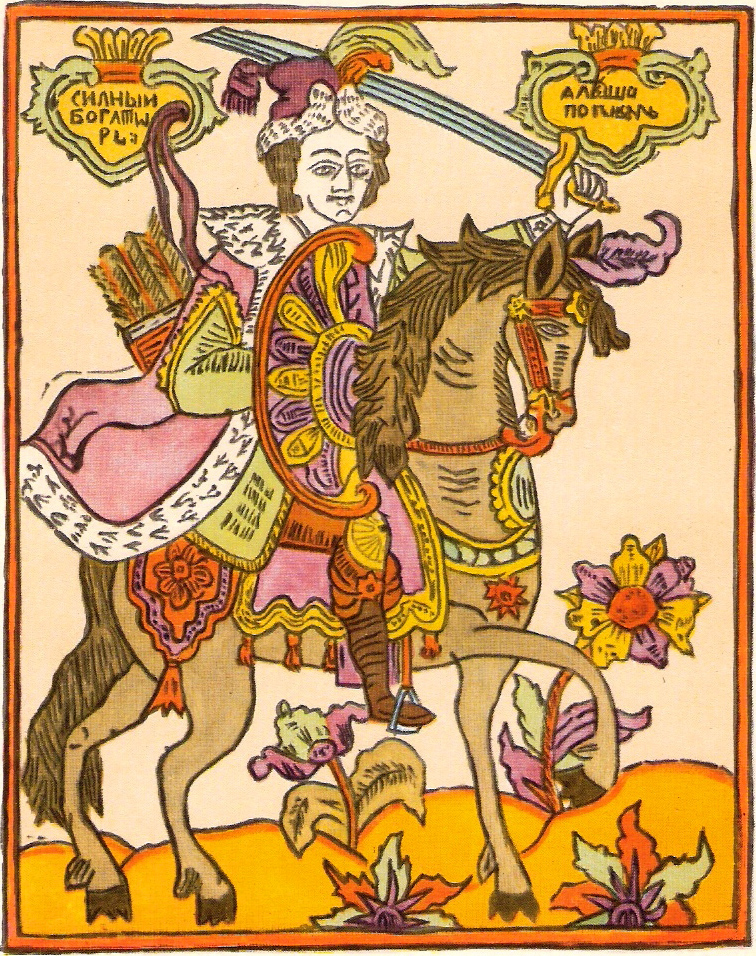

The third, and the youngest personage, was Alyosha, who was also an archer, and was known for his dexterity and cunning; he was a bit of a trickster, as was appropriate to his youth.

Although later stories put all three bogatyrs together, the three were actually heroes of separate legends at different times, and it is likely that the three were first connected in the 16th century skomoroh performances – satirical street plays, whose actors were later persecuted by the Orthodox Church.

Many other heroes in these epic tales are of the same type – physically strong, good natured, and always ready to fight their enemy, (usually for three days and three nights).

Upon occasion they shoot an arrow outside the scene of battle to help them find direction, or hunt something or someone down, either for sustenance or to physically weaken their ‘unorthodox’ adversary, before killing them in some gruesome way.

Arrow in Russian Fairytales

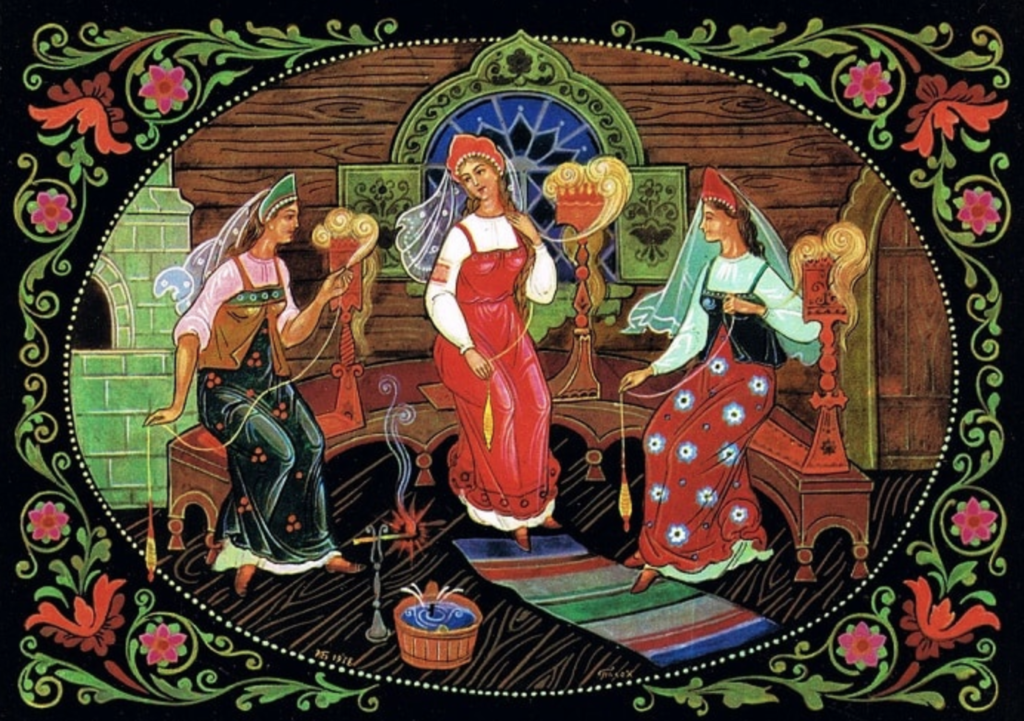

Arrows are frequently met in fantastical Russian fairy-tales, and very often the storylines are connected with ‘wife-seeking’, or weddings. Arrows also often lead the protagonists somewhere important or possess the power to rid a person or an object of a curse, or the magical properties invested in him or it.

The wedding scenarios reflect various stages of real-life courtship, most commonly finding and selecting the bride, ‘buying’ or ‘winning favour’, and ‘securing the bride’. By far the most famous Russian fairy-tale of this genre is the tale of ‘The Princess-Frog’.

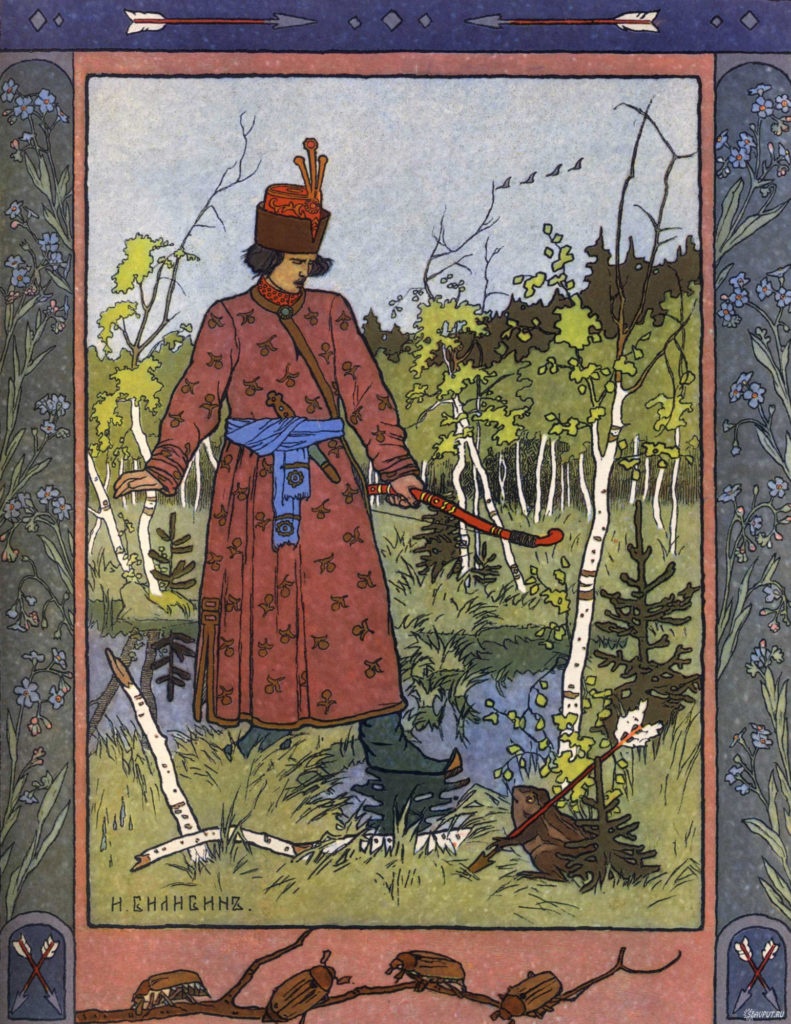

The adaptations of this story are found in both Eastern and Western culture. In the standard Russian version, a tzar orders his three sons to get married. All three go out into the field and, facing in different directions, shoot an arrow into the sky.

Wherever the arrow lands, there each will have to find a wife. Typically, the youngest, often considered the weakest, the simplest, or the least ambitious, finds his arrow near the frog. The frog turns out to be a bewitched princess, but the spell is not broken by the typical ‘frog kiss’.

In most Russian adaptations, the frog is not cursed – she is in fact a ‘shapeshifter’, who is a beautiful young woman in ordinary life, but is forced to live in this form for one reason or another, most often as a means of avoiding a forced marriage to an ugly old suitor. In actuality, the future wives were never determined ‘by lot’ or chance – marriages were usually arranged.

‘Shooting arrows to find a bride’ is of course a metaphor for a hunt. To show his virility, the protagonist needs to be a good shot. In earlier traditional weddings (that usually lasted for three days), on the first day men would celebrate by shooting at the ‘front of the bride’s house’ (strelyat’ po basul’kam).

The hunting and sexual symbolism is obvious. In this custom a new husband shoots at the façade of the house of his wife, until she eventually surrenders, and the wedding can continue to the next stage – the wedding feast. When rifles became commonplace, they were also used for shooting at ‘basul’kas’. In wedding songs, a man is often personified by a ‘falcon’ (sokol) who hunts a swan (lebed’), his chosen woman.

There is also a bridal custom for the woman, analogous to the idea of the Princess Frog ‘chance’ method, which was often employed in the Russian villages. Single women would walk out into the yard and shout, “Where will I find my husband?”- and would then walk into the direction where the first barking of a dog was heard.

Another curious, though much later and lesser known fairy-tale, deals with an interesting aspect of Slavic courtship – ‘smotrini’, the official first date, where, after meeting the bride’s parents, the groom is weighing up the potential bride’s attributes.

Three brothers, archers and hunters, are instructed by their mother to stick their arrows into the ground overnight. They return in the morning to find their arrows beautifully painted. Next night they do the same but hang around to see who did the painting.

They witness three spoonbills (waterbirds) fly down only to turn into fine beautiful women once they touch the ground. These shapeshifters paint the arrows again and each says: “This arrow belongs to my sweetheart”. Real customs would often dictate that a woman had to demonstrate her beauty not only through her appearance, but through her crafts.

It is refreshing to see the shapeshifting brides also making the choice of partner, as well as the other way around. Often in these narratives, the Russian brides, though modest, are perhaps not as submissive as in other cultures. (Some would argue the same trait persists today.)

Another common courtship scenario in these tales involves a young man having to prove his worth as a ‘husband material’ to a young woman’s father. The father is often a tzar, and the young suitor is often a poor farmer’s son.

Skill in archery is usually one of the tests he has to undergo, and the feat he must achieve is to ‘Robin Hood’ the arrow – or something along those lines. This is the most realistic task he is asked to do. And yes, he has to complete three tasks, as the number three is the universal magic number in most, if not all, Russian stories of all genres.

When fairy-tale arrows are shot at random, it suggests a method of choosing by lot. Things are essentially left to chance, and most often this method is employed by young or immature fairy-tale characters. It signifies the lifting of responsibilities and the leaving of things to Fate or some ‘higher power’.

The motif of allowing Fate to decide destiny in Russian folklore is usually also connected to the idea of direction, as in the random shooting of arrows. The arrow in Russian fairy-tales may also be used to distract – but again, in order to aid searching for, hunting down, or winning the desired wife.

The Harsh Realities of Siberian Upbringing

Ancient Russian warriors of those times were excellent archers and horsemen, and many battles were won thanks to that. The bow and arrow provided one of the most common games for children, along with ‘stick fighting’, ‘bareknuckle boxing’, ‘tree climbing’, ‘chasing games’ and other activities aimed at developing physical strength and prowess.

Archaeological finds from Ancient Novgorod (10-13th. C.) feature a vast number of children’s bows, most not exceeding one metre in length. And many Siberian teenagers and women had to learn to shoot a bow in self-defence, during periods when the father of the house, most often a professional ‘druzhina’ warrior, was away working or hunting.

As one contemporary account puts it: “Boys of taiga live by one craft – shooting. Parents teach their young. They (teenagers) don’t exercise anything else in their lives, but this one craft. They can kill the strongest beast: a bear, a moose, a deer…and even birds, not only those on water, but also in the sky.”

One of the most popular training games was as follows. Six sticks in two rows of three were stuck into the ground; he who hit the stick advanced forward by the distance of his bow’s length. If he missed, the opponent took his arrow away from him.

But not all games were fun. Some were rather cruel, intended to prepare a young warrior for the grown-up realities of the harsh Siberian landscape. For example, a young boy would stand in the middle of an open field, whilst being shot at with blunt arrows.

His task was to try to avoid them. The speed and quantity of arrows would gradually increase. And strength and stamina were taught by giving a boy a blunt axe with which to chop wood.

It would take hours, and his palms would likely be bloody and calloused by the time he had finished his task. His eyesight would be tested in a simple way – “if he can see the middle star in the Greater She-bear (Ursa Major) his eyes are good”. Thus, by the age of fifteen or sixteen, he would be ready for any eventuality.

Brilliant article

Thank you for the research