Nils Visser follows his curiosity to meet the maker of the Rebel bow

One of the boons of conducting historical research is running across ‘archery nuggets’: wee insights into behaviour that typify an archer and is therefore immediately recognisable to another archer. An example would be a 14th century medieval Saracen writer, generally speaking with a mindset almost alien to my own, admitting that there are heated discussions about the best type of arrow. That’ll bring me a broad grin, recognising those passionate debates from just about any pre- or post-shoot event I have ever attended. Lately I have been examining archery in the first half of the 20th century and have stumbled across so many such nuggets that it has been hard to retain objectivity and not lose myself in romantic nostalgia for a period which I have started to call the ‘era of adventurous archery’.

Picture black and white photographs of gents and ladies in white trousers and fine dresses on meticulously manicured lawns, but also of rugged hunters wearing floppy bush hats, peering intently at their targets, possibly fierce bears in Alaska or big game on the African savannah. Most archers will recognise the legendary names who strode through wild woods with bow in hand and arrow ready: Howard Hill, Fred Bear, Doug Easton, Roy Hoff, Art Young, Saxton Pope, Ben Pearson and many more. These are the Ernest Hemingways and Teddy Roosevelts of archery.

There are nuggets aplenty. In England, regarding the usual discussions about the best type of arrow, were these supplied by Highfield? Buchanan? Aldred? James Duff, who worked in the archery goods business in England was much amused by the various proclamations regarding the superiority of one arrow over the other, as he knew that arrow maker Harry Purle made the arrows for all three companies. Experimentation took place too, something probably familiar to anybody who has ever spent time with a bowyer. In the States, bowyer Abner Shepherdson made a 150 pound yew bow for Dr. Paul Crouch. Though Crouch shot an arrow 311 yards and six inches with this bow, neither man was satisfied with this result, resulting in a discussion in which the merits of the used light flight arrow were compared to the possibilities of using a shorter arrow in an Oriental trough, or else a heavier arrow. Shepherdson also designed a take-down yew bow, one of which was to come into the possession of Irish Senator St John Gogarty who would give or sell it to John “Fighting Jack” Churchill in 1938, after which Churchill used the bow to deadly effect during the evacuation of Dunkirk in May 1940.

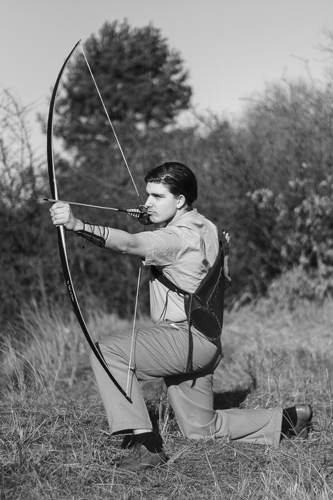

Photographer Carlo Robbé has captured the spirit of high adventure with his photographs of the Rebel bow in action

There was also the connection to the magical silver screen. For the 1938 movie The Adventures of Robin Hood, Howard Hill gave archery instructions to both Errol Flynn and Basil Rathbone, and in 1952 “Fighting Jack” Churchill worked with Robert and Elizabeth Taylor in the movie Ivanhoe. Both archers took on roles of extras as well.

To a contemporary archer, bound by rules and regulations as well as wrangling with insurance companies, the era of adventurous archery seems to have been characterised by a remarkable freedom. The pictures and films we are left with exude an energy of rediscovery and limitless exploration, as well as an apparent sense of fraternity. Walking around with my head in the clouds, imagining I was teaching the basics of archery to Elizabeth Taylor back in the 50s or some such nonsense, it did not take much to make me relinquish any notion of sensible objectivity. The final nugget came when I was suddenly confronted with a series of black and white pictures advertising the Rebel bow, made by an archery outfit in the Netherlands called Fairbow. The pictures struck an immediate chord. The first ones were clearly based on pictures I had seen of Basil Rathbone, and subsequent ones gave a nod of obeisance to poses of other 20th century archery legends I had come across. All conjured up that seemingly free spirit which marked the time of adventurous archery and, needless to say, I was intrigued. Not much later, at the SPTA’s St George’s Shoot in Somerset in the spring of 2014, I encountered one of these Rebel bows and saw for myself that the maker was capable of far more than just commissioning artful pictures. The bow was a beauty and seemed to perform flawlessly, much to the delight of its owner.

Time, I thought, to find out more about the background of the Rebel, so I made an appointment with bowyer Magén Klomp in Amsterdam to satisfy my curiosity. He was not in his office when I arrived, though I didn’t mind as the space also functions as a display room, with traditional archery goodies on show everywhere: quivers, bracers, arrows, mead, beef jerky, arrowheads, a display case with historical arrowheads, fletchings in many shapes and patterns, gloves, tools, DVDs, books and bows of course. Yew war bows, light bamboo bows, the Maciejowski bows, horsebows, Manchu bows, Vertex longbows and Rebel bows were all on display. I felt like a kid in a candy shop and would have happily stayed there for hours, but I was directed to the workshop where I found Magén covered in sawdust. He beckoned me, shook my hand and commenced into immediate conversation about a new wood working tool he had acquired. This was followed by a guided tour through his workshop, which had rack upon rack filled with some familiar and many unfamiliar tools of the trade. I must confess I forgot half of the names and functions of these, which were patiently explained to me, being still in a swoon with evocations of stalking through the wild places of the earth and storming castles while the cameras whirred away, kitted out with some of the stuff in that display room.

Magén assured me that I was not the only one and my reaction to the Rebel pictures was precisely what he had hoped for.

“There have been hints that it’s just a marketing gimmick,” he said. “And I’d be lying if I said I didn’t hope to create a wider interest in the Rebel. But whenever I start a new product I immerse myself in it completely, read everything I can find and test materials. So the pictures are a tribute too, to archers like Howard Hill. How can I not admire such a man? Rather than trying to present the Rebel as an entirely new creation of my own, I am acknowledging where the inspiration came from.”

He shared the sense of adventurous freedom which I had picked up on but was far more eager to talk about the actual bow than the pictures. Conception had been a mix of nostalgia and a dare.

“You make fine longbows Magén,” someone had told him after a conversation about Hill, Bear, Young and Pope, “But I don’t see you making a bow the way Howard Hill did.”

That was enough incentive for Magén to have a new closer look at his two Howard Hill style bows, made by John Schulz, who was one of Hill’s students. Though both the traditional longbows which have made Fairbow a familiar name, and the Howard Hill bows, are relatively simple in design compared to a recurved composite horn bow, for example, there were significant differences which made making a Rebel bow a challenge indeed.

Magén’s take on the bow sees the riser as a separate addition, rather than incorporated into the fiberglass laminate of the belly

“The limbs are much thinner than those of a longbow,” Magén explained. “It enhances the bow’s qualities to be sure, but it also means that the limbs are more likely to warp during the production phases. As usual, that means extensive tillering,” he grinned ruefully.

It has also meant making a number of prototypes, which he has tested and measured extensively. He also engaged the services of experts who used special software to analyse the moulds he made for the Rebel, and who could advise small changes to optimise the moulds. This helped him delete the initial glitches which invariably accompany the making of a whole new type of bow, and he is now gearing up to the production of the second generation of Rebels.

Magén’s Schulz bows, and other Howard Hill bows he has seen, make extensive use of bamboo and fibreglass. Hill took the longbow as his starting point and adapted this, reducing the thickness of the limbs and adding a riser. Magén’s voice is full of respect as he describes how the use of fibreglass was pretty much in its infancy and how much pioneering went on in those days. He uses many of the same techniques and materials for the Rebel, though he adds that there is always something of his own in bows he designs and makes. In this case it is the riser, which is not incorporated into the bow by being covered by the layer that makes up the belly. Rather, it is attached as a separate component. The Rebel’s risers are made from classical wood types with natural colouring; Magén doesn’t hold with artificial colourings. Another ‘addition’ is the horn overlay on the bow nocks. Hill and Schulz only did this for their luxury models, but for the Rebel it is a standard feature which is friendlier to both the nock and the string.

The quiver seen here has been designed based on old photographs to help recreate the spirit of early 20th century adventurous archery

“The Rebel is an ultra-light bow,” Magén explained. “Because there is so little mass in the working parts it shoots very fast. Moreover, the Rebel design means there is very little hand shock. You do need a different technique for shooting it vis-à-vis the longbow, but that is not hard to master. Basically, it’s a very durable bow and once you get to know it, and listen to it, it’ll really serve you well, especially if you want to shoot for longer periods of time during a field course.”

Over the years Fairbow has developed the concept of ‘made to measure’ into something of a trademark, and this applies to the Rebel as well. The bows aren’t spat out by a machine, each is made individually and by hand. The only concession to Ford’s production lines is that Magén usually works on a couple during each production cycle. This allows for a great deal of scope with regard to individual customer wishes. Out of curiosity, Magén made himself a 100 pound Rebel bow, just to see how well he could shoot with it, though he prefers using his other, lighter Rebel during 3D shoots. The quality of a hunting bow, he explained, was not so much the high draw weight, which mattered in war bows. The bow, in combination with the type of arrows used, must pack enough of a punch to cope with the larger and more dangerous targets, while at the same time being a bow you could use all day long without risking an injury. The targets in 3D shoots are unlikely to move and charge you if you miss of course, but they do require an archer to complete a course without sacrificing efficiency due to sore arms. The Rebel bow is eminently suitable for this, and Magén was also keen to point out that those fans of the bow who insisted on having the type of arrows Howard Hill would have used were strictly instructed not to bring those to 3D shoots, where targets are quickly shredded by double-sided blades or pounded by bodkins. He laughed, and admitted that he felt his responsibility for all the bows he makes and sells does not end at the moment of sale. He even awards competitors at some events a considerable monetary prize if they perform well using one of his bows. Nothing gives him more satisfaction than to see the products he makes used well and used skillfully. After all, that is what bows and arrows are for.

And it’s such a delight to shoot. It’s fast, it’s furious and it’s just beautiful to look at (in action as well as on a shelf).